A World of Solitude

Un mundo de soledad

Gisela Heffes

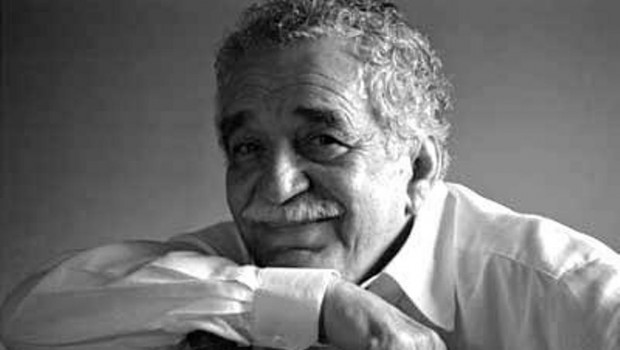

With the death of Gabo, the nickname for the widely known writer, Gabriel García Márquez, a whole generation of the twentieth century’s finest writers seems to be vanishing. The author of one of the most extraordinary novels ever written, One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), just passed away leaving a sense of emptiness and sadness for both readers and literary critics.

I read García Márquez for the first time in high school, again when studying at the University of Buenos Aires, and again in graduate school at Yale. How can we ever forget the amazing characters that inhabit his unique worlds? The Buendía family genealogy, Remedios the Beauty fading in the sky after ascending in the later afternoon or the eccentric Melquíades who predicts the fate of the family, tightly bound to the story of Macondo, the imaginary town where the novel develops. While his work is mostly known by the so-called “magic realism,” García Márquez also wrote chronicles, journalism, memoirs, and also had been in charge for many years of the EICTV (Escuela Internacional de Cine y TV / International School of Film and TV) in San Antonio de los Baños, Cuba. This school, founded with Argentine filmmaker Fernando Birri and Cuban producer Julio García Espinosa, has formed and developed many generations of students from Latin America, Asia and Africa.

García Márquez was a part of the Latin American “boom” generation, in which writers such as Argentine Julio Cortázar, Mexican Carlos Fuentes, Peruvian Mario Vargas Llosa, Paraguayan Augusto Roa Bastos explored the limits of literary imagination and created a new genre that combined beautiful literary styles with a most dramatic –and sometimes humorous– assessment of Latin American history, politics and social problems. In García Márquez’s case, his narrative illustrates the most prominent aspects of Latin American modernity, such as experimentation with popular topics, writing and deconstruction of the patriarchal tradition, a typically peripheral intent of both dominating universal literature –a characteristic that is very typical in Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges– and narration and its opposites. García Márquez’s texts are usually closed, dated historically and aspire to totality. I have written on García Márquez’s literary production as a “classic” –especially One Hundred Years of Solitude– for its realistic character and its historical connection, its capacity to synthesize several aspects of human life such as love, tradition, politics, and a wide range of different conflicts as well as aesthetic features that emerge in the novel.

When García Márquez received the Nobel Prize in 1982, the Swedish Academy highlighted the significance of “his novels and short stories, in which the fantastic and the realistic are combined in a richly composed world of imagination, reflecting a continent’s life and conflicts.” (Nobelprize.org) However, one of the most significant aspects highlighted by the Swedish Academy in order to understand his legacy and impact in the international cultural arena are García Márquez’ trajectory as a writer and his social and political commitments. It is noteworthy that his work has triggered all sorts of approaches from the most disparate positions and perspectives.

One paradigmatic example is the perspective from Vera Szeckacs, García Márquez’s translator to Hungarian, who established an analogy between Macondo and Hungry in their equally bloody history, shared peripheral condition underlined by the permanent waiting for “progress,” and their solitude. García Márquez’s literary production has been compared with all possible books, musicals, colonial chronicles, plays, and world nations. However, I agree with García Márquez when he once stated irreverently or sarcastically that no literary critic would ever be able to transmit the real vision of One Hundred Years of Solitude until he or she rejects the most evident premise that the novel lacks completely of seriousness. It will be of course the task of his readers to determine the accuracy of this statement. In the meantime we will rejoice reading one of the most engaging and beautiful writers of the past century.

Con la muerte de Gabo, el apodo ampliamente conocido de Gabriel García Márquez, la generación de los mejores escritores del siglo XX parece desvanecerse. El autor de una de las mejores novelas de todos los tiempos, Cien años de soledad (1967), acaba de morir dejando un vacío y tristeza para ambos: lectores y críticos literarios.

La primera vez que leí a García Márquez fue en la preparatoria, lo volví a leer en la Universidad de Buenos Aires y de nuevo lo leí en el doctorado en Yale. ¿Cómo podemos olvidar los personajes que habitaban sus universos únicos? La genealogía de la familia Buendía, Remedios la bella esfumándose en el cielo después de su ascenso por la tarde o al excéntrico Melquíades quien vaticina el destino de la familia tan cercana a la historia de Macondo , el pueblo imaginario donde se desarrolla la novela. Aunque su trabajo es principalmente conocido por el Realismo Mágico, García Márquez también escribió crónicas, textos periodísticos, memorias y dirigió la EICTV (Escuela Internacional de Cine y TV ) en San Antonio de los Baños, Cuba. La escuela fundada con el cineasta argentino Fernando Birri y el productor cubano Julio García Espinosa, ha formado y desarrollado muchas generaciones de estudiantes de America Latina, Asia y África.

García Márquez fue parte de la generación del “boom” Latinoamericano, en cuyos escritores como el argentino Julio Cortázar, el mexicano Carlos Fuentes, el peruano Mario Vargas Llosa, el paraguayo Augusto Roa Bastos exploraron los límites del lenguaje imaginario creando un nuevo género que combinó un estilo bello de literatura con un dramático y a veces humorístico dominio de la historia de América Latina , su política y problemas sociales. En el caso de García Márquez su narrativa ilustra los aspectos más prominentes de la modernidad Latinoamericana como la experimentación con los temas sociales , hablar sobre la deconstrucción de la tradición patriarcal, el intento periférico de dominar la literatura universal –una característica típica en el argentino Jorge Luis Borges–, sus narrativas y sus opuestos. Los textos de García Márquez son usualmente cerrados fechados históricamente y con aspiraciones a la totalidad. He descrito a la producción de García Márquez como clásica–especialmente Cien años de soledad-por los personajes realistas y su conexión histórica, su capacidad de sintetizar diversos aspectos de la vida humana como el amor, la tradición, la política y un amplio rango de diversos conflictos así como características estéticas que emergen en su novela.

Cuando García Márquez recibió el Premio Nobel en 1982, la academia suiza subrayó el significado “de sus novelas y sus cuentos, en donde lo fantástico y lo realístico se combinan en un rico mundo compuesto de imaginación, reflexiones sobra la vida de un continente y sus conflictos.” (Nobelprize.org) Sin embargo, uno de los aspectos más significativos que subrayó la academia sueca para poder entender su legado e impacto en el espacio internacional de la cultura es la trayectoria como escritor de García Márquez y sus compromisos sociales y políticos. Es importante señalar que su trabajo ha detonado todo tipo de posiciones y perspectivas.

Un ejemplo paradigmático es la perspectiva de Vera Szeckacs, la traductora de García Márquez al húngaro, quien estableció una analogía entre Macondo y Hungría en su igualmente sangrienta historia, la compartida condición periferia acentuada por el deseo de “progreso” y su soledad. La producción de García Márquez ha sido comparada con todos los libros posibles, musicales, crónicas coloniales, obras de teatro y naciones del mundo. Sin embargo, acuerdo con García Márquez cuando en una ocasión afirmó en tono irreverente o sarcásticamente que ningún crítico literario sería capaz de transmitir la verdadera visión de Cien años de soledad hasta que él o ella no rechazara la premisa más evidente: la novela carece de seriedad. Será, desde luego la tarea de sus lectores la de determinar la fidelidad de esta afirmación. En el mientras tanto, gocemos de la bella lectura de uno de los escritores más atractivos del siglo pasado.