Fakes in the World of Photography

Analissa Moreno

Fakes are possibly the most fascinating slice of the art world. From time to time, a suspicious work slips by authentication experts and draws an extraordinary amount of media attention. Additionally, museums learn of possible fakes through the grapevine and reexamine pieces in their collections. Art institutions and private collectors have spent large sums of money purchasing works of art to add to their collections, only to discover the purchase was a fake, leaving them with a worthless piece of artwork and a headache. Fortunately, an increase in the scientific examination of dating paints and canvas types has assisted in the detection of faked works of art. Sadly, the reality is that although institutions have detected fakes in their collections, any number of major museums, galleries, and private collections may own a fake and not even know it.

One sector of the fraudulent art market, less publicized, is photography. Forgery– a concept hardly associated with photography – runs rampant in the art market today. For decades, photography has fought to be regarded as a collectable fine art only to be set back by a number of issues. For most art collectors, the key pitfall of photography is the possibility of reproduction. Since its development in 1839, photographs – to some extent – could be printed and reprinted indefinitely. Over the years, the rise of new and better technology made the ease of reproducibility increase exponentially. Copies of high-valued prints could enter the market years after the death of the artist and still fetch a reasonable sum. Estates of deceased photographers attempt to control the number of new prints with specific edition numbers and strict regulations for reproduction, but forgeries still occur. Unfortunately, for every new legitimate copy, a never-ending stream of illegitimate copies appears.

For photography, defining ‘fake’ or ‘forgery’ with regard to photography is probably the least difficult issue. Finding a definition for the word “vintage” is necessary to further the authentication process and define forgery. In March of 2004, the International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR) held a conference pertaining to issues of authenticity in photography. During the conference, the guest panelists attempted to define “vintage.” Denise Bethel, Chairman of Photographs at Sotheby’s New York, gave the auction house’s definition of a vintage print as a print made within ten years of the negative. Peter R. Stern, an art law attorney with McLaughlin & Stern LLP, defined a vintage print as a print created at or around the time the negative was made. The discussion continued and in the end, the group concluded there is no one definition for ‘vintage’ photographs.

But how do you detect whether or not a photograph is authentic? Auction houses run under strict deadlines and cannot send a photograph out for scientific authentication, some of which can take up to six months, which is too long to wait for an answer. Instead, as Bethel says, they rely on a “quantity versus longevity” experience. Quantity experience is seeing and studying a considerable body of work by one photographer at any given time, and subsequently encountering them frequently. Longevity experience is the increase of knowledge due to examining photographs over the course of many years. Although both quantity and longevity experience may benefit a sale, sometimes even the experts are fooled.

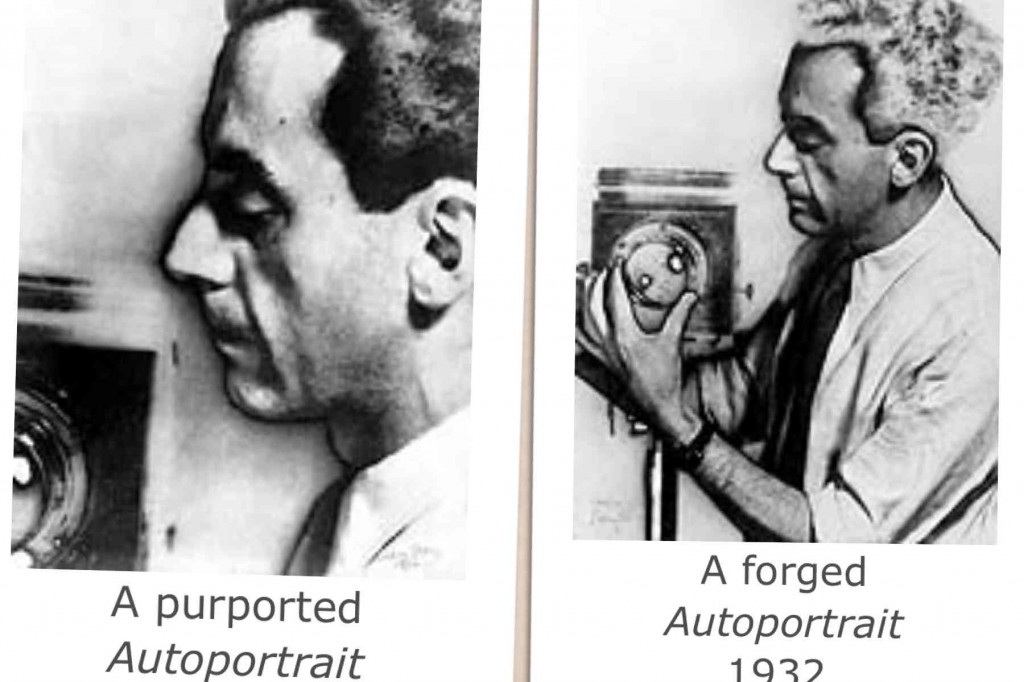

The first instance of an expert being deceived is a case of fake Man Ray photographs in the early 1990s. Werner Bokelberg, a German photographer and collector, had one of the largest collections of Man Ray photographs at the time. Maria Morris Hambourg, the head of the Photography department at the Met, wanted to borrow Bokelberg’s photographs for a Man Ray retrospective set for 1998. When she first viewed the photographs, she thought they were impeccable and was convinced they could make a wonderful exhibition. However, one thing troubled her – where was Bokel, as his friends knew him, getting his photographs? Surely, owning 78 impeccably printed Man Ray’s was too good to be true. Unfortunately for Bokel, this was the case. After some investigation, Benjamin “Jimmy” Walter was the confirmed culprit. Walter, the son of a man believed to have befriended Man Ray during his time in Paris, inherited the collection at the time of his father’s death. In the early 1990s, Walter approached Bokel with four exceptional prints. Over the next few years and spending roughly $2 million, the 78 became apart of Mr. Bokelberg’s collection.

Man Ray expert Gérard Lévy, whom had presided over a Man Ray sale in November 1983 at Hôtel Drouot, authenticated the photographs. So how could they not be legitimate? Hambourg had noticed an Agfa stamp on the back of quite a few of the images. Agfa, a well-known producer of photographic paper, tested the photographs. Their tests revealed that the suspicious photographs were printed on ‘Nostalgia’ paper, a paper produced between 1992-1993. Therefore, it was inconceivable that the photos could have been produced during Man Ray’s lifetime. Bokelberg demanded Walter to return his money, but only received half. Walter received his faked photographs in return, stating he had spent the other $1 million. Is it possible that printer X (Bokelberg’s name for the mysterious printer) was paid the other million? We may never know.

The second case of forged photographs concerns photographs by Lewis Hine. Hine, an early 20th century photographer, is known for his photographs documenting child laborers and their dreadful working conditions. During the Great Depression, he documented workers in steel mills, powerhouses, and other hard labor environments for the Works Progress Administration. Upon his death, Hine’s complete archive was housed in the New York Photo League cooperative. In 1998, Michael Mattis, a physicist and avid photography collector, discovered a number of Lewis Hine prints he acquired were of a suspicious nature. Mattis sent a few photographs from his collection, along with Hine photographs from other collections, to his friend Paul Messier.

Messier, an independent photographs conservator, developed three tests to prove their authenticity. These tests concerned manufacturer logos, optical brightening agents (OBAs), and paper fiber analysis. Every single photograph Mattis had sent fit two out of three tests, thus proving their inauthenticity. Mattis, as well as six important New York photography dealers, went hunting for the perpetrator. All eyes fell on Walter Rosenblum, a photographer and former president of the Photo League. Rosenblum, a protégé of Hine’s, was suspected of printing images from old Hine negatives from the Photo League storage and signing them himself. Mattis, the only victim to not have signed a Non-Disclosure Agreement, settled out of court.

The most recent case of forgery concerned 19th century French photographer Crespy Le Prince. In March 2011, Artcurial Deauville sold a number of French 19th century salt prints by Charles Edouard de Crespy le Prince. Numerous dealers and collectors specializing in 19th century photographic acquisitions purchased prints and negatives at the sale. Later that year, the independent specialist for the sale, Grégory Leroy, filed an initial complaint with the French Police; this complaint concerned the authenticity of the photographs sold at the March auction. The sale lots had supposedly come from Crespy le Prince’s family, but the provenance was not watertight. Jean-Claude Vrain, a well-known 19th century photo collector, realized his purchases were fakes upon receiving them post-sale. Unfortunately, information concerning this case is lacking, but proves that 19th century photographic processes can be faked as well.

Ultimately, after reviewing these few cases, one realizes that there may never be an end to forgeries in photography. One can only hope innocent collectors are wary of any purchase in the future. With the 20th century photograph market dwindling, a rise in fakes may occur, but with the rules and regulations set out by estates, the likelihood lessens. Further development of authentication tests and research into paper processes will help stop forgeries, but the problem of missing negatives remains. It is impossible to account for all the negatives and prints made by a photographer in his or her lifetime, leaving gaps for fakes to be reproduced. With each new case comes the question of the future. In the current and future art market, is it possible that fakes will continue to appear? We can only wonder.

Posted: August 25, 2014 at 9:36 pm