Florencia in Havana

Héctor Manjarrez

Translated to English by Tanya Huntington

Many moons ago, when Florencia met Fidel Castro at a film festival in Havana, she almost fainted. The Stallion, as his subjects called him, appeared by her side out of the blue, just inches away from a modest buffet table that she had been contemplating hungrily, but with a lack of interest, craving, or appetite.

There were times when she liked feasting even less than not eating at all, because in this world there are so many who have next to nothing, or less than nothing, to eat.

“And where are you from?” asked a voice that unmistakably belonged to her hero, as always in uniform, sans necktie or pistol, but surrounded by a halo of grace and childlike sensuality reminiscent of those naïve, orthodox Christs you see in religious icons.

“From Mexico, Comandante,” she answered, legs trembling, as if she were a schoolgirl.

“You don’t say, Me-xico.” He divided the three syllables into two groups. “And how do you find Cuba?”

Florencia found Cuba splendid, gallant, heroic, and moving, as well as hot, delicious, and sensual. She had been on the Island a few months now, having enrolled in some courses at the famous screenwriting school, and every day, she found more insignificant reasons to admire and grow fond of a people who were writing their own history “against the current, against the grain and against the darkness.”

For all those who have not experienced that moment when the gaze of the People finds itself in the mirror and is enlightened, this sentiment may seem somewhat puerile and dim. Indeed, by then the Cuban Revolution had already insisted over and over, every day, for many years–like nuns in their convents–that its slogans and its actions and its sacrifices were all for the forces of Good, which would vanquish the Evil One and give hope to the poor and all people of goodwill around the globe, even the Africans. But this was precisely what moved Florencia, this stubbornness of sorts, both childlike and calculated, that was Cuba, although she didn’t know quite how to put this to the Heroic Stallion, her olive-green founding father, who regarded her with his small, fixed, cold, impenetrable eyes as if he could get into her head and heart whenever he liked.

Instead, Florencia first thought she would faint, then feared she would faint, then felt she would faint (après Fidel, who said everything at least three times), and as the seconds ticked away, the Supreme Commander seemed to grow impatient, very impatient, and fixing his gaze upon her, as God did unto Abraham, he repeated the question:

“And how do you find Cuba?”

And Florencia–one of the most serious, most consistent, most earnest people on the planet–was seized by a fit of laughter. “Oh, crap! I blew it!” she thought, glancing sidelong at the Stallion, the living legend who only smiled when he thought he should smile and who never, ever laughed.

“Are you all right, compañera?” The Caudillo interrogated her using the formal You, which seemed the only appropriate way to speak to this woman of merry eye but puritan, prudent demeanor.

“Forgive me, Commander-in-Chief!” blurted out the beautiful, but stern Comrade Florencia. “I don’t know how you expect me to answer such a complicated question!”

The Revolutionary Gorillas were on the verge of storming the couple at the buffet, but a wink from their handler, who knew the Comandante like the lids of his own eyeballs, stopped them mid-step and they tried to pretend they had been magnetically drawn to the Argentinean Camembert and local lobster hors d’oeuvres that ordinarily only foreign guests were allowed to consume.

The Commander gazed in Perplexity but also with Curiosity and a smidgen of Sensuality at this woman who, now practically guffawing, had laughed in a throaty voice one moment, a singsong voice the next, then a hiccoughing voice the next. Like a firefly sneezing… the Despot said to himself, surprised at the strange image that had popped into his head. Like a beautiful firefly with the flu… fresh, innocent, touching, and mesmerizing.

It had been a long time since the Tyrant had laughed, except at some dim-witted gringo on the TV. Since he had enjoyed the simple things in life. Since he had caught himself observing a woman in delight, except for little eleven-year-old Revolutionary Pioneers with luminous glows in their dark eyes who embodied the future of the Revolution.

This Mexican woman, on the other hand, reminded him of La Lollo, that fluffy Italian actress. Admittedly, she wasn’t that luxuriant, but she seemed to share the gift of natural good faith and spontaneous laughter, of happiness and joy, of La Bachata.

It’s true, the gratifications of the Maximum Leader were of a completely different nature: his body had subsumed into his mind, and his mind was drawn solely to pondering tactical and strategic issues: how to correct errors, how to get ahead of the future, how to anticipate the gambits of the damned enemy and the weaknesses of allies, how to keep the People in high spirits, how to introduce a stick between the spokes of the apocalyptic motorcycle of imperialism, when to launch a campaign, when to trade bishops or rooks, when to sacrifice pawns, when to appear in Revolution Square and electrify the entire nation and his admirers abroad with a fascinating monologue, mysterious and revealing at the same time, delivered to the fatherland by its father, concerned and admirable all at once.

Indeed, for just a few seconds, the legendary Infidel had found solace in the nervous, contagious laughter of a much younger woman who was much less tall and revolutionary than he was, like a child amazed by a pet’s devotion, like an islander who sometimes wonders what might be happening on the Mainland.

That such a great man, so tough and weather-beaten to boot, should get all wound-up by the stupid reaction of an intelligent woman rather than by her intelligence, is no mystery. We know what chauvinism is, Comrade! I have pointed it out and explained it on many occasions!

Needless to say that (as far as we know) the Caballo Cubano did not indulge in the pleasures of other Dictators; to be specific: atrocious acts of vengeance and nubile young girls (Mao), insatiable cruelty (Stalin), machinery of Evil (Hitler), embezzlement and mockery (Pinochet), unbridled rage (Trujillo and Somoza and Papa Doc), mean-spirited scorn (Franco), love for diamonds and mansions (the Africans), savagery (every single member of the Argentine military), thirst for blood (Pol Pot).

The Cuban Commander-in-Chief was not like any of those monsters, no sirree.

He was different; he despised the privileges and pleasures taken by other irreplaceable leaders of the People. He, Fidel, was a despot only for your own good, never, ever for his own. All of the benefits, for you; all of the responsibilities, shared; all of the power, for him.

“I find Cuba to be an extraordinary, place, Fidel!” Florencia heard herself saying to Him. “There’s nothing like it in the world… It is like being in a laboratory where, every day, experiments are carried out to produce the New Man.”

“And the New Woman,” added, pensively, the not-so-young-anymore Stallion-in-Chief.

“And the New Children of a new fairy tale,” added Florencia, in a truly corny outburst.

“You make films?

“Yes, Commander.”

“Revolutionary cinema must be made!”

“Yes, Commander, revolutionary cinema must be made, but I’m afraid I make petit bourgeois cinema!”

The Great Leader’s eyes opened wide.

“But, why would you do such a thing?”

“Because I can’t help it, Comandante!”

The Hope of the People honestly did not know what to say.

“It’s stronger than I am,” Florencia confided, like one who suddenly opens her heart not to a bartender or a girlfriend, but a priest. “No matter how hard I try, or how sincerely, to make revolutionary cinema, I can’t: totally petit-bou cinema comes out.”

“But radical petit-bou, at the very least?” Inquired the Hero of Moncada, with a touch of concern.

“Oh, yes, definitely: very radical petit-bou,” Floriencia rambled on, despite the fact that she was normally more stony than Stone itself, realizing that she was at a loss, unsure whether she was making fun of the Great Stallion unintentionally, or whether she was making a spontaneous confession, as if he were a psychoanalyst whose blameless patient finds herself compelled to recall dreams or, if all else fails, to invent them.

It is a serious, a very serious, an extremely serious matter to disappoint psychoanalysts, priests, and leaders of the People; after all, they are doing it for us.

The New Martí looked at Florencia distractedly and fixedly at the same time.

“I suppose (I have observed, I have noticed) that where art is concerned, it is difficult to maintain a fully revolutionary consciousness.”

“Yes Comandante, ever so difficult.”

“What’s more,” he added, more firmly, ”coming from a once admirable country like Mexico, where the Counterrevolution has taken hold so cynically, so shamelessly, so brazenly in every corner, every day… It must be very difficult, so as not to say impossible, to preserve one’s revolutionary consciousness, faith, willpower!”

“Oh, Mexico is a very difficult country, Comandante! We don’t have… how shall I put it… we don’t have the same idealistic frenzy as you do here on the Island!” she exclaimed, on the verge of paroxysm.

At that moment, a historic one for her, the gods were generous with Florencia and saved her from having to compulsively respond to all of the Heroic Stallion’s reflections: a mulatto man of exquisite beauty appeared, doted with as great a purity as the Archangel Gabriel, as well as a sublime set of buttocks, to usher the Comandante away after whispering a few concepticos and palabricas in his ear.

“I have to go now, Comrade. The Revolution never sleeps,” the Great Bearded One said, and in a notoriously old-fashioned gesture, took her hand and kissed it, leaving behind (inadvertently, no doubt) a tiny drop of saliva somewhere between her index and ring fingers.

Like a wandering jasmine tree, the Horse strode off, leaving behind an intoxicating aroma of gravity and nobility and faith formerly known as the odor of sanctity.

People were staring at Florencia in repudiation (in case she had offended the sacred Leader) or with envy (in case he had been pleased). It was not clear which of the two emotions ran stronger at the cocktail party, where nothing more was going to happen that could possibly be, forget about unforgettable, memorable even.

Some filmmakers and actors and actresses were deprived of the pleasure of shaking the great leftist leader’s right hand, and yet another Latin American deity, García Márquez himself–who just now rushed in, smiling–would be bereft this night of publicly mingling with his dear old friend, Fidel.

He–who made public appearances on very rare occasions, slightly more often than Our Lady of El Cobre–seemed to have singled Florencia out, as God does His saints; which was precisely why none of the other guests dared approach the interloper, who decided to down a second and then a third daiquiri in six gulps, a practice most unusual for her.

“The Comandante must have thought I was drunk… better get just a little tipsy.”

And then, as Comrade Florencia made a beeline for the door, no one daring to address or detain her as she crossed the room, the revolutionary potency of the daiquiri inspired her to murmur with a silly, gleeful giggle:

“Just like Cinderella!”

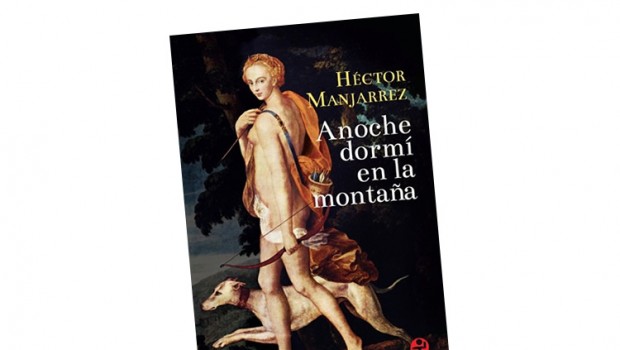

• The above is the first of three sections that comprise “Florencia en la Habana”, published in the short-story collection Anoche dormí en la montaña (Ediciones Era, 2013).

Posted: March 9, 2014 at 4:44 pm