Geraldo de Barros: Thowing the Dice

Fernando Castro

Download Complete PDF / Descargar

If we could only keep our happy or sad memories we would go crazy. Fortunately, there are others.

– GERALDO DE BARRO

Unbeknownst even to himself, in 1979, Geraldo de Barros suffered his first attack of cerebral ischemia. He was fifty-six years old. Up until the Seventies, it had been a good decade for Geraldo. In 1972, Hobjeto, the furniture factory of which he was co-owner had reached its maximum expansion employing over seven hundred people. His furniture designs had received several awards thus fulfi lling his desire to socialize art by allowing as many people as possible to use it in their lives. The commercial success of the Hobjeto chain made him a wealthy man. He was able to build a lofty new home with a studio and travel to Europe with his family. In 1975 his daughter Fabiana had found photographic prints he had done twenty-five years before; this discovery renewed his enthusiasm for photography. He also reestablished contact with the artistic circle of his younger years. However, the economic crisis in Brazil was beginning to affect his furniture business and Geraldo found himself under increasing stress.

It was his wife Electra who first noticed his impaired speech and motor coordination. “Speak normally, Geraldo. I cannot understand what you are trying to say,” she told him one morning. He asked for a pen but when she gave it to him, his fingers could not hold on to it. Only after being hospitalized did the family find out what had happened to him. “Too much stress and too much smoking,” the doctor said. He had to slow down.

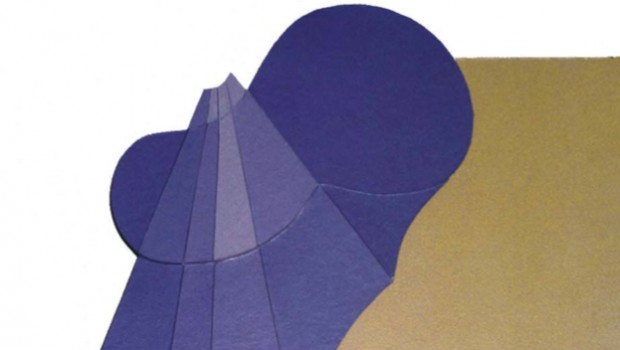

Although physically diminished, Geraldo remained as lucid as ever and was determined to continue to be the artist he had always been. He was able to sketch geometric patterns like those he had done during the fifties when he was one of Brazil’s most renowned Concrete artists. With the help of his assistant José Suares, who executed the paintings from his sketches and instructions, Geraldo produced an astounding new series of abstract Concrete works. The Brazilian art world re-discovered his works. In 1979 they were selected to be shown at the XV Bienal Internacional de Arte de São Paulo. His restless creative mind overpowered his physical vicissitudes and he radicalized his idea of socializing art further by using industrial materials instead of paint. Using Formica, Geraldo produced the series Jogos de Dados, a name that echoed Mallarmé’s seminal calligraphic poem Throw of the Dice. His newly created works gained him the honor to represent Brazil at the 1986 Venice Biennial. “After I got sick, I became better,” Geraldo said once with his characteristic sense of humor.

It was the life and honor that the young Geraldo could have only dreamed of. He had begun his artistic voyage at the age of twenty three by enrolling at the Associação Paulista de Belas Artes. He took drawing and painting lessons with Clóvis Graciano, Colette Pujol,

Takeshi Suzuki, and the great Japanese master Yoshiya Takaoka. With other artists he formed Grupo 15 and developed an expressionistic way of painting. Seeking to improve his knowledge of art, Geraldo frequented the Biblioteca Municipal de São Paulo. He discovered the Theory of Gestalt, the work of Paul Klee, and the art of the Bauhaus. At that time, Geraldo also made friends with Athaíde de Barros and together they improvised a photographic laboratory. Fascinated by the creative possibilities of the medium, Geraldo bought a 6×6 twin-lens Rolleiflex camera. Michel Favre, his most reliable biographer to date, states that Geraldo “started frequenting the only place in Sao Paulo where photography lovers would meet, the Foto Cine Club Bandeirantes.” Nevertheless, “he was one of the youngest members and his ideas did not tally with the only approach favored by the club, pictorialism.” Geraldo’s main premise about the medium boiled down to what he spelled out as such: “For me photography is a process of printing.”

He took lessons in drawing and painting with Clóvis Graciano, Colette Pujol, Takeshi Suzuki, and the great Japanese master Yoshiya Takaoka. With other artists he formed Grupo 15 and developed an expressionistic way of painting. Seeking to improve his knowledge of art, Geraldo frequented the Biblioteca Municipal de São Paulo. He discovered the Theory of Gestalt, the work of Paul Klee, and the art of the Bauhaus.

From about 1948 to 1950, Geraldo began a series of experiments unmatched in the medium of photography. He employed several techniques including straight photography, pinhole photography, solarization, multiple exposures and alteration of negatives by cutting, scratching and painting. Fortunately, the Museu de Arte de Sao Paulo Assis Chateaubriand, founded in 1947, had a new Italian director, Pietro Maria Bardi, who did not believe in favoring one form of art over another. Bardi asked Geraldo to organize a photographic laboratory for the museum. It was there that in 1950, Geraldo held the landmark photographic exhibit Fotoformas that brought together his photographic experiments. Aside from the impact this exhibit had among artists and photographers at the time, the practical result of it was a grant from the French government to study printing in France.

Although the two years Geraldo spent in Europe led to a forty-two year hiatus in his practice of photography as a fine art, they also transformed his life. In Italy, he met Giorgio Morandi; in Paris, Francois Morellet; in Ulm, Otl Aicher; and in Zurich he visited Max Bill, whom he had already met in São Paulo. Some writers have also mentioned a meeting with Henri Cartier-Bresson. Undoubtedly, it was Max Bill who had the greatest impact on Geraldo as he was the rector of the Hochschule fur Gestaltung in Ulm and one of the apostles of Concrete art both in Europe and Brazil. When Geraldo returned to São Paulo, he became one of the founders of the Grupo Ruptura of Concrete art that also included Luis Sacilotto and Waldemar Cordeiro. It was a movement that advocated an end to figurative (representational) art and promoted an objective art that pointed only to itself. It was also an art with the social mission of making art accessible to people’s lives as designs for modern living. Some Concrete artists de-romanticized the role of the artist and regarded themselves as mere workers. They also saw their vision of art as a timely one vis-à-vis Brazil’s ongoing modernization. Geraldo became a prominent member of the group and participated in national and international exhibits of Concrete art.

In 1954 received an artistic award that was handed to him by the president of Brazil, Getulio Vargas himself. That same year his friend, Joana Cunha Bueno, introduced Geraldo to Frei João Batista Pereira dos Santos, a Dominican priest at the Chapel of Christ the Worker. The chapel congregated an important group of artists, architects, and intellectuals interested in providing workers with tools for survival and cultural improvement. The chapel itself featured works by prominent artists like Alfredo Volpi. Geraldo and Frei João Batista established Unilabor, a worker-owned cooperative for making furniture. Geraldo participated enthusiastically in this utopian experiment designing “intelligent” furnishings for the masses that the Unilabor workers would produce. However, by 1964, the cooperative was beset with financial and managerial difficulties; the ultra-rightist military coup of March 31st made the experiment politically suspect. Moreover, Unilabor’s management considered that he was dispensable. Geraldo left Unilabor and joined Aluisio Bioni in creating the Hobjeto privately-owned furniture factory. The name was a combination that Geraldo came up with: Hoje (today) and Objeto (object) = today’s object.

In 1960 Brazil inaugurated its new capital, Brasilia. Around this time, Geraldo discovered Pop Art and returned to figurative painting. In 1966, together with the artists Nelson Leirner and Wesley Duke Lee, he opened Rex Gallery & Sons in the back room of one of the Hobjeto stores. Wesley Duke Lee remembered that they placed a large bronze plaque with the name of the gallery —like a British bank would—to show they meant serious business. The gallery was a place of happenings and sponsored an eclectic assortment of art that was different from the extremes that had been so common for the last fifteen years. According to his friend Nelson Leirner, Geraldo confronted a new critical universe by appropriating “outdoors” (billboards?) he found in the street and modified them by painting them and making collages with them. “His concept was to bring elements from the street to the inside and from the inside back to the street.” However, Geraldo stopped his re-launched Pop artistic career in order to focus on Hobjeto. Leirner states that Geraldo was able to stop art and then start again like Duchamp used to stop to play chess.

Those years were the preamble to his first stroke. In 1988, Geraldo suffered a succession of new strokes that further incapacitated him and confined him to a wheel-chair. Nevertheless, he continued to sketch and plan new works.

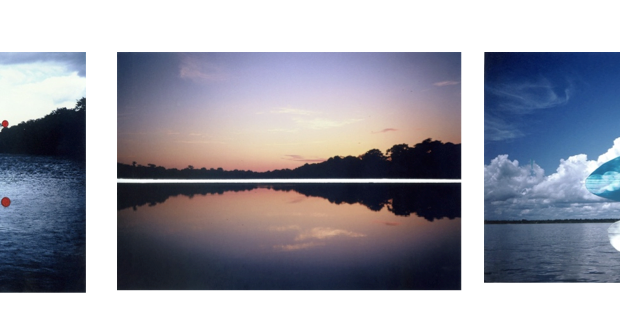

In Geraldo’s story there is an important chapter where the main protagonist is his daughter Fabiana de Barros —an artist in her own right. She played a crucial role in the recognition of her father’s work. It was thanks to Fabiana’s efforts that in 1993, the Musee de L’Elysée in Lausanne, Switzerland brought to Europe a major exhibition of his work: Geraldo de Barros: Peintre et Photographe. This exhibition opened the door to the international recognition of Geraldo’s work and the publication of several books about his work. Curiously, this renewed interest in his oeuvre focused on his photography of four decades earlier. Fotoformas, the series of works that propelled his career in 1950, were exhibited, written about, and understood anew fortysomething years after their first showing. Geraldo was not immune to this enthusiasm. Once again, he put the dice on an assistant’s hand and threw more numbers. In the last two years of his life, Geraldo produced two hundred fifty new photographic works. He titled the series Sobras because they were made from photographs of his family and travel albums that were never destined to anything but mementos. “A photograph belongs to the one who makes something out of it, not necessarily to the one who took it,” Geraldo once said.

About the Artist

Geraldo de Barros was born in Xavantes, São Paulo (1923-1998). He started his career as a traditional painter, but soon became closer to experimental art. In the 1940s, when other photographers were doing straight documentary and portraiture photography, Geraldo de Barros was creating abstract photos which led him to become one of the main exponents in his country. He was the founder of many and very important art movements like Grupo 15, Galeria Rex, Grupo Ruptura or Grupo FormInform and the Hobjeto Industry, among others. In 1993, his entire photographic work was recovered and exhibited by the Musée de l’Elysée in Lausanne, Switzerland. This exhibition was shown in São Paulo in 1994 by the Museu da Imagem e do Som (MIS), and a catalogue was published (in Portuguese and French) with the 100 pictures on display at the exhibition.

Posted: April 14, 2012 at 10:35 pm

Wonderful images! This is a magnificent photographer. Shame on Google for not positioning this post upper! Thank you =)