How You (un)See Us

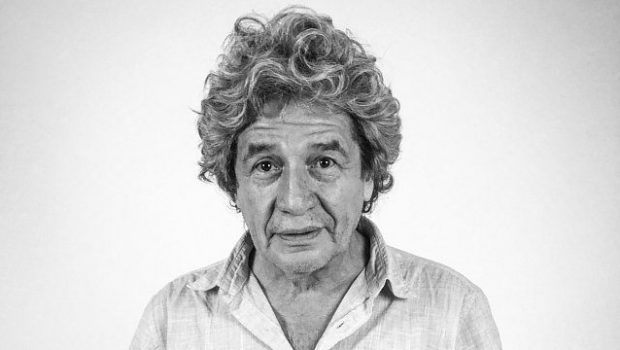

José

My name is José. I am Mexican. And, yes, I am undocumented. I understand that none of this might surprise you, as my name may suggest my nationality and my nationality my (lack of) legal status. I don’t blame you. This is, after all, the triple filter through which American society sees (or unsees) most of us. What you may not know is that I also have a middle name, “Ángel,” and a last one which, out of fear of deportation, in recent years I have often been forced to omit. But let’s get it over with. Here: in Illegal, my memoir, I admit only to “N,” as in “nobody,” whereas it ought to be Navejas. And this is just to say—I may lack legal status, but I have a full name, a particular history, a voice.

I am a husband, a parent, a published author, and, for over a quarter of a century, an expert in the ontological dilemma of undocumentedness.

It is not surprising either that this article would appear only now, weeks after the controversy generated by Jeanine Cummins’ American Dirt. After all, it is in keeping with American tradition that, in matters involving the undocumented, undocumented voices are usually the last ones to be heard, our stories the last ones to be seen. Old habits die hard. Just look: even on clear sunny days, as we push heavy lawnmowers across enormous suburban backyards, you delude yourselves into thinking of us as denizens of a distant realm of shadows. And this, the blinding power of imperial gaze is, I think, what is most troubling about Cummins’ novel. Not the blatant appropriation of another’s story, but the hypocrisy and desensitization that turns profound human suffering into gaudy melodrama.

Contrary to what others think, I am not convinced that anybody has a monopoly over any one narrative. If that were the case, then the best interpretation of Emerson’s work would necessarily possess the stern dull Anglo-Saxon character of a Carlyle or a Nietzsche. And, nonetheless, it is, in my opinion, in the luminous pages of a young Caribbean man, José Martí, where Emerson’s magic is in full display.

The same principle could have applied to Cummins’ novel. As an outsider, she could have offered a fresh perspective on the profound tragedy visited upon Mexicans. But instead, she chose to depict the flirtation with crime, the grisly imagery, and the hyperbolic helplessness of a people whose greatest virtue might just be survival itself.

But none of this surprises me either. During these few weeks of inflamed rhetoric, victimization, and laudable efforts of the Latinx literary community to reform American publishing, something no one seems to have noticed is that what needs to be reformed might not only be the publishing industry, but the American reader. Or rather, how America chooses what it reads. While the opinion of a celebrity might be innocuous when choosing the best deodorant, selecting what books will inform us and shape our view of reality is quite different.

The premise of a celebrity as literary oracle might be a good plot for a reality show, but it does nothing to explain the matter at hand. But perhaps that is the point—to observe profound social reality through the comical lens of TV mythology, in which case Cummins’ novel provides the perfect script. American Dirt has reduced a great transnational human crisis to the status of what another commentator has called “trauma porn,” placing its characters in a sociohistorical vacuum and denying them any psychological depth. In doing so, the culprits of the tragedy playing out south of the border—America’s gun production and drug consumption, Mexico’s vast inequality and educational failure—go on unchallenged and unanswered.

Cummins has successfully recreated the narrative American readers want and need—the image of “the other” they have been amusing themselves with and profitably exploiting since the 19th century. And that’s how you, America, (un)see us. Rather than seriously considering the existential dilemma of millions of people who are, like me, permanently stuck in a legal limbo, liberal Americans prefer to imagine us as fictional characters—a vast congregation of shadows inhabiting America’s underbelly.

I can picture him, the average reader, thinking he’s diving into an accurate depiction of profound human misery, utterly oblivious to the fact that he’s responding to his own preconceptions, his ingrained Platonic forms. Does he think about this false sense of empathy? Does he think how, through this vicarious experience, he has helped usher the author into the rank of millionaire?

But that might just be the secret lurking behind America’s creative genius—trivializing suffering in the service of entertainment. In writing American Dirt, Cummins carried on the American tradition of mimicry. She wrote the script for the minstrel show demanded by the current political and cultural climate, and the American audience readily bought into it. Perhaps that’s why apologists of the American publishing industry and those who have been seduced by its money-making miracle were quick to bestow Cummins’ novel the paradoxical status of an instant “classic.”

In a recent interview, Cummins lamented the tenor of the conversation around her work. A victim of her own commercial success and cultural naiveté, Cummins has also regretted that her novel had not been written by a slightly browner person. But no brown person would belittle the deep trauma of violence, of forced displacement, of walking into the endless night of America, just to realize that their humanity has been illegalized.

This is just to say—there are plenty of brown writers, Ms. Cummins, some authors of their own personal narratives, myself included. Then the question becomes: is America willing to listen?

José Ángel Navejas came to the United States from Mexico in 1993. He is the author of Illegal: Reflections of an Undocumented Immigrant and Invierno. In 2019, the Spanish version of Illegal became the first book translated by the University of Illinois Press in its 100-year history. He was Scholar in Residence at Monmouth College (2014), delivered the Dean’s Diversity Lecture at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (2017), and has been invited to speak at the University of Notre Dame (2019), Princeton (2018), Northwestern (2014-2015), and the University of Chicago (2015), among many others. Follow him on Twitter: @joseangeln000

©Literal Publishing

Posted: March 5, 2020 at 11:19 pm

I am privileged to know José and to call him a friend. He is living what used to be called the American dream. Unfortunately, that dream has been transformed into what at times would be more accurately characterized as a nightmare.

I am profoundly touched by José’s tenacity and determination to carry on in the face of the obstacles that have been placed in his path. It is incumbent on all of us to join in his struggle, because it is the struggle for the future of our country.