In Praise of Luxury

En defensa del lujo

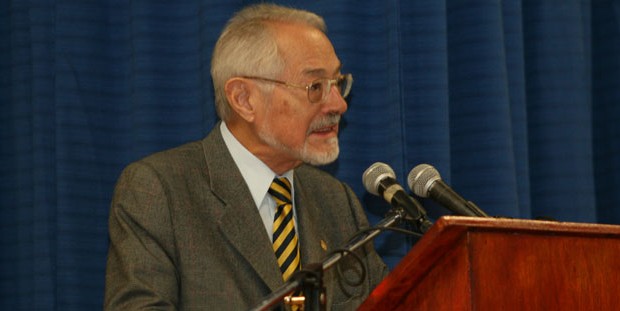

Yvon Grenier

Luxury is something enjoyed as a superfluous addition to the ordinary necessities of life. Christian culture framed it as a foolish and worthless form of self-indulgence. Luxury is materialistic and, worst of all, it is a pleasure: two sins in one. A defining feature of modernity is that it cultivates self-criticism, as Octavio Paz explained in many essays. Since modernity and materialism are intimately related, criticism of materialism and its satellites (cult of progress, positivism, instrumental reason, technology) is central to critical assessments of modern time. One can trace a continuous line between the pre-modern, modern and post-modern renditions of the anti-materialist pose. All have in common the prejudice that materialistic craving distracts us from loftier conceptions of the good life: religious or aesthetic revelations, nationhood, class consciousness, community, and so on. When Voltaire wrote «Le superflu, chose très nécessaire» (poem Le Mondain, 1736), the penseur des lumières was not rejecting materialism per se; only the narrowly materialistic definition of life and its necessities. He was highlighting the importance of poetry, art, and love, none of which are immediately “useful” or historically contingent. For Octavio Paz, poetry and eroticism are not merely necessary additions to material well being. Like André Breton and the Surrealists, he viewed the poetic revelation and eroticism (la luxure!) as essentially “revolutionary”, for they subvert (rather than complement) the dominant values and institutions of our time. Similarly, the French intellectual Georges Bataille, who had some influence on Paz and much on Mario Vargas Llosa, identified both eroticism and the dépenses improductives (such as the Potlatch) as “transgressions” in a bourgeois society based on the totems of productivity and repression of natural impulses. The denigration of materialism and instrumental reason led many artistic vanguards of the twentieth century to embrace irrationality and even violence. That risqué penchant would have been hazardous for public safety had not its exponents been so typically and mercifully harmless (at least to others).

Radical critiques of materialistic indulgence also meet in demanding tougher standards for others than for themselves. The Catholic Church, Marxists in power, and bourgeois “anti-bourgeois” poets, to name a few, are not known for snubbing privileged access to material gratification. I have yet to see any of my leftist university colleagues turning down a pay raise (or for that matter, not asking for one) for fear of increasing inequalities in our community. Incidentally, the new “cultural” left did itself a favour when it shed its itchy populist skin: now it can be both subversive and audaciously chic. In short, in many tirades against the “fetishism of commodity” one finds an “enough for me, way too much for you” undercurrent (the Malthusian version: enough of me, way too many of you), one that usually goes undetected.

The fact and the matter is that consumerism does provide satisfaction, even pleasure, to the many. Who said that money is the sixth “sense” that allows one to better enjoy the other five? That’s how most people feel. Greater material satisfaction killed the revolutionary drive in the working class. It probably caused the Berlin Wall to tumble, more powerfully than a yearning for liberal democracy. In both cases the outcome was good for freedom and well-being. Anti materialist and anti-consumerist folks come in different shades, but they all have one key feature in common: they hail from the middle class or higher; they speak with their mouth full. Poor people are not anti-materialist. Nor are poor countries. Of course, for most people the point is to have enough money so that money is not the point anymore. But how much is enough? Marx was wrong to see Communism as the final stage of human development, after capitalism, but he was intuitively right to consider abundance as the necessary step toward a superior, post-“necessity” stage of history. In fairness, the liberals are the ones who were right all along: they praised prosperity without ever presenting it as an end in itself. Well fed citizens can sit and afford the luxury to deliberate about the right path to the Good Society. So-called post-materialist societies are in fact prosperous societies, in which general wealth create the conditions for the emancipation, not from basic material needs but from dependence to the fulfillment of those needs. Whether we like to say it or not, democracy is a luxury that is affordable only at a certain stage of material development. All right but, isn’t prosperity and productivism a threat to the environment? Yes, but in a democratic society, it also provides a fertile ground to imagine both political and technological solutions to this vital problem. Inequality is a problem too, to be sure, but what does luxury have to do with it? If everybody had access to luxury (whatever that means in each historical context), would it be still considered luxury? What do we want to redistribute: wealth or poverty?

I propose to give a break to individuals and societies who wish to improve their material conditions of living. Better deal with difficult social policy issues clearly and directly, away from fuzzy and duplicitous malaises about materialistic self-indulgence. And let’s celebrate all the little pleasures that life brings to us.

Lujo es todo lo que se disfruta como añadido superfluo a las necesidades ordinarias de la vida. La civilización cristiana lo catalogó como una forma vana e insensata de autocomplacencia. Aparte de ser materialista, el lujo es un placer, lo que lo convierte en doble pecado. Como en muchas ocasiones lo explicó Octavio Paz, si algo define a la modernidad es su cultivo de la autocrítica. Toda vez que la modernidad y el materialismo están íntimamente relacionados, la crítica del materialismo y sus satélites (el culto del progreso, el positivismo, la razón práctica, la tecnología) está en el centro de las valoraciones críticas de nuestro tiempo. Podemos trazar una línea continua entre las manifestaciones premodernas, modernas y posmodernas de la postura antimaterialista. Todas comparten el prejuicio según el cual las inclinaciones materialistas nos desvían de las más altas aspiraciones de la buena vida: las revelaciones religiosas o estéticas, el amor a la patria, la conciencia de clase, la comunidad, etc. Cuando Voltaire escribió: “Le superflu, chose très nécessaire” (en su poema Le mondain, 1736), no es que el pensador de las Luces rechazara el materialismo per se, sino tan sólo la estrechez de la definición materialista de la vida y sus necesidades. Con ello hacía hincapié en la importancia de fenómenos como la poesía, el arte y el amor, ninguno de los cuales posee inmediata “utilidad” o limitación histórica. Para Octavio Paz, la poesía y el erotismo no son meros añadidos necesarios al bienestar material. Al igual que André Breton y los surrealistas, consideraba la revelación poética y el erotismo (¡la lujuria!) como esencialmente “revolucionarios”, por cuanto subvierten (más que complementar) los valores e instituciones dominantes en nuestros tiempos. Del mismo modo, Georges Bataille, quien ejerció cierta influencia sobre Octavio Paz y mucha sobre Mario Vargas Llosa, definía tanto el erotismo como los gastos improductivos (según ocurre en el potlatch) como “transgresiones” en el seno de la sociedad burguesas basadas en los tótems de la productividad y la represión de los impulsos naturales. Denigrando el materialismo y la razón práctica, numerosas vanguardias artísticas del siglo veinte llegaron a abrazar la irracionalidad e incluso la violencia. Tan arriesgada propensión habría resultado peligrosa aun para la seguridad pública si sus exponentes no hubieran sido siempre tan típica y piadosamente inofensivos (al menos para los otros).

Los críticos radicales de la propensión a la vida regalada comparten otra característica: exigen mucho más de los otros que de sí mismos. La Iglesia católica, los marxistas en el poder y los poetas burgueses “antiburgueses”, por nombrar sólo a unos cuantos, no se distinguen por desdeñar el acceso al disfrute material. Todavía no he visto que ninguno de mis colegas universitarios de izquierda rechace un aumento de sueldo (o bien, que no lo solicite) por temor a fomentar las desigualdades dentro de la comunidad. Dicho sea de paso, la nueva izquierda “cultural” hizo bien al despojarse de su quisquilloso barniz populista: ahora puede ser a un tiempo subversiva y atrevidamente chic. Dicho en dos palabras: en muchos de los ataques al “fetichismo de la comodidad” lo que se ve es una actitud encubierta de “bastante para mí, demasiado para ti” (en su versión malthusiana: bastantes en mi caso, demasiados en el tuyo), la cual suele pasar inadvertida.

El hecho es que el consumismo proporciona satisfacción, incluso placer. ¿Quién ha dicho que el dinero es el sexto “sentido” que le permite a uno disfrutar mejor de los otros cinco? Así es como piensa la mayoría. Una mayor satisfacción material mató el impulso revolucionario de la clase obrera. Probablemente fue, más que los anhelos de la democracia liberal, lo que provocó el derrumbe del Muro de Berlín. En ambos casos, el resultado fue bueno para la libertad y el bienestar social. Los antimaterialistas y los anticonsumistas se presentan en diferentes tonalidades, pero todos comparten un rasgo clave: surgen de la clase media o más arriba; hablan con la boca llena. Los pobres no son antimaterialistas, como tampoco lo son las naciones pobres. Desde luego que para la mayoría de la gente se trata de tener dinero sufi- ciente para que el dinero deje de ser lo más importante. ¿Pero cuánto es bastante? Marx se equivocó al ver el comunismo como la fase final del progreso de la humanidad, después del capitalismo, pero acertó intuitivamente al considerar la abundancia como un paso necesario hacia un estadio superior, superada ya la “necesidad”, de la historia. Justo es reconocer que fueron los liberales quienes tenían la razón desde el principio: defendían la prosperidad sin siquiera presentarla como un fin en sí mismo. Los ciudadanos bien alimentados pueden darse el lujo de reunirse a deliberar acerca de cuál sea el camino correcto para llegar a la Sociedad Ideal.

Las llamadas sociedades posmaterialistas son de hecho sociedades prósperas en las que el bienestar general crea las condiciones para la emancipación, no a partir de las necesidades básicas sino de la dependencia respecto de la satisfacción de dichas necesidades. Nos guste o no decirlo, la democracia es un lujo que sólo puede uno darse en cierta etapa del desarrollo material. ¿Pero no es acaso la prosperidad y el productivismo una amenaza para el ambiente? En efecto pero, en la sociedad democrática, dicha condición es terreno propicio para imaginar soluciones políticas y tecnológicas a tan vital problema. Desde luego que la inequidad es también un problema, ¿pero qué tiene que ver con ella el lujo? Si todos tuvieran acceso al lujo (independientemente de lo que éste sea en cada contexto histórico), ¿seguiría considerándose lujo? ¿Qué es lo que necesitamos redistribuir: la riqueza o la pobreza?

Propongo que dejemos en paz a los individuos y las sociedades que desean mejorar sus condiciones materiales de vida. Lo mejor será tratar de manera clara y directa los difíciles temas de política social, que nos olvidemos de esos turbios e imprecisos malestares que supuestamente provoca la autoindulgencia, y que celebremos todos los pequeños placeres que la vida nos da.