An Author’s Rights.

Tanya Huntington

“You are the books you have read, the paintings you have seen, the music heard and then forgotten,

the streets explored. You are your childhood, your family, selected friends, a few loves, a great many nuisances.

You are a sum reduced by infinite subtractions.”

The Art of Flight, Sergio Pitol

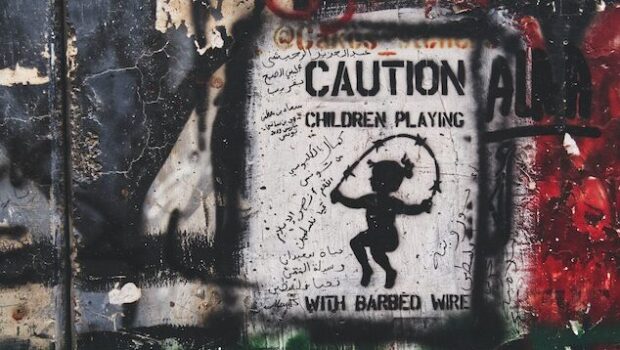

Years ago, while passing through a picturesque town in the state of Jalisco known as Lagos de Moreno, I happened to notice a bridge over a dried-up gully. It bore a sign announcing a $1 peso toll to cross the river that once ran underneath. I remember wondering, is the river still a river once it’s dry?

That image came back to me this month within a very different context: that of how the flow of works generated by artists is interrupted by our inevitable demise.

When an author passes away, her publications are recast as an elegy of her entire career, briefly occupying once again the privileged tables and displays at the forefront of bookselling establishments. Plus, her editor can now in good conscience market the definitive complete works, once her desk drawers have been emptied of any manuscripts that may have lingered there.

As for the recently deceased visual artist: his passage is rewarded with an immediate boost in his monetary assessment–determined per square meter of artistic production–given that overnight, his works have become a commodity limited to those already in existence.

A switch hitter myself between letters and visual imagery, I can attest to the fact none of us like to dwell on the potential difficulties to be experienced in a (hopefully) distant future by our heirs: our sons and daughters squabbling over a certain painting, the possibility that one’s beloved spouse could very well end up sitting on the rights to a novel published long before you met her.

And yet, these things do happen.

Here in Mexico, there have been several cases in recent history that smack of extreme injustice: the writer sequestered during her old age for fifteen years by two trusted figures she had designated as concierges, then buried in secret after having allegedly named one of them as her sole heir in a suspicious new will; the widow who took legal action against an author for selecting an epigraph that quoted her late husband’s verse without her permission; the exiled painter who, eschewing matrimony, failed to formalize her relationship with her partner of decades and whose valuable legacy wound up in the hands of a niece on another continent; the interdisciplinary artist who died unexpectedly of AIDS in a distant land –but this fact cannot be mentioned by his curators, at the risk of incurring the wrath of the conservative, provincial clan that controls his avant-garde oeuvre.

Indeed, even in the best of families the sudden introduction of a valuable long-term legacy tends to end in strife. Like the land parceling system introduced by President Cárdenas in the 1930s, once you fast-forward a generation or two, it becomes a question of how to distribute a finite possession among an increasing number of hungry mouths. Those who suffer most are the deceased’s adoring public; the rights to specific titles, for example, can become obscenely expensive, making it more and more difficult for new readers to access works considered to be classics.

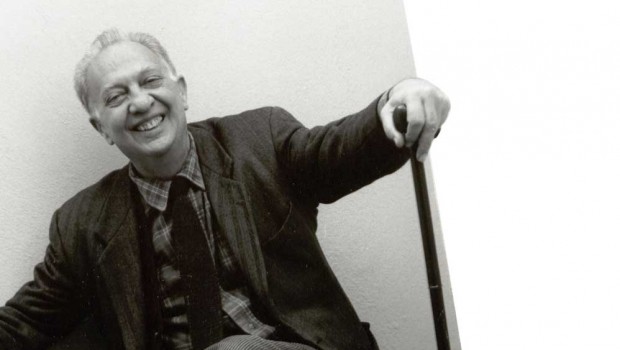

This thorny issue is on my mind because of the unfortunate situation affecting the great Mexican author Sergio Pitol, winner of the Cervantes Prize. Pitol suffers a degenerative disease that has left him with, among other symptoms, aggravated aphasia. A lifelong bachelor, although continuing to make public appearances, he chose in the face of this condition to reside peacefully within his inner circle, formed by his personal secretary, his chauffeur, and his cook.

Until his cousin filed a lawsuit last fall in the state of Veracruz, claiming that he was not of sound mind and body –possibly because Pitol had, in turn, accused him of administering a contraindicated medicine– and should be compelled to accept his “family’s” care. Fortunately, the judge ruled against him and since then, the head of the state Department of Integral Family Development and two professors from the Universidad Veracruzana have been empowered to make decisions regarding Pitol’s wellbeing.

Yet even this ruling, as it would seem, is not enough to prevent these woodwork relatives from acting against his wishes, trying to harness the river of his literary production even before it has dried up completely –eagerly anticipating, no doubt, the future toll to be charged to all those who would cross the bridge spanning Pitol’s many important works.

After gastric hemorrhaging left him briefly hospitalized, this same cousin has once again garnered media attention by claiming that the author’s appointed caretakers are negligent. Those of us who know him are, first and foremost, overjoyed at the news of his recovery. Now it is up to us as colleagues, friends and readers to rush to Pitol’s aid and insist upon his right to privately determine not only how he lives, but how he dies.

Cover image: Alberto Tovalín

Tanya Huntington is a contributing writer at Literal. Follow her on Twitter at @TanyaHuntington.

Posted: March 3, 2015 at 7:30 am

Only someone who has never met Pitol’s family can think they mean harm to him. How easy is to choose a side without knowing the complexity of circumstances surrounding this issue.