Lessons for Modern-Day Autocrats: Farewell to the PRI

Lecciones para el moderno autócrata: Adiós al PRI

Yvon Grenier

What is following the Cold War is not the “end of history,” as we all know by now. Authoritarian and semi-authoritarian regimes of all stripes continue to coexist, often quite harmoniously, with the Liberal democratic hegemon, with a relatively new addition to their rank: let’s call it the Hybrid. This relatively new type of authoritarian regime is a product of both globalization and ideological exhaustion. It features a minimalist and typically incongruous official ideology and self-describes as a producer of “results” (prosperity, security, sovereignty) more than teleological or utopian dreams. What this reminds us is that the “end of history” is in fact an end to grand ideological confrontation, rather than the universal triumph of a pensée unique.

Hybrids come in two varieties: Market-Leninism and Illiberal democracies. The first thrives in China, Vietnam and increasingly in Cuba. For some observers, the so-called “Beijing Consensus” (single party monopoly + state capitalism) will actually dominate the 21st century. “Illiberal democracy” is flourishing in countries like Russia and its satellites, as well as in Venezuela, Nicaragua and Equator. Both have in common a faith in stateness and strong leaders, and a disdain for due process. (There are obviously important differences between them as well: this is not the place to examine them.) In countries ruled by Hybrids, nationalism and populism have supplanted the “thick” political ideologies of the past. Even in a country as saturated with politics as Chávez’s Venezuela, the Revolución is a style, an ambiance (a color: red) and a rhetorical device, not a coherent system of political beliefs.

For practioners and fans of Hybrids, democracy isn’t nearly as attractive as what American sociologist Theda Skocpol, in her analysis of modern revolutions, called “popular involvement in national political life.” Plebiscites, elections (even rigged), emotional connection to the leader, routinized attachment to the party or the god Revolución can accomplish that. In economic policy, the name of the game is export-led capitalism tempered by political patronage (sociolismo).

One could be excused to think that the 20th century Mexican PRI was ahead of its time!

Today’s politics is less “ideological” in the same way that “new wars” are no longer manifestations of ringing ideological conflicts between nation-states. They are also more messy, complex and unpredictable. Mobilizations from below, even uprisings, express cravings for practical gains (e.g. affordable food) or values (“Dignity before bread” was the slogan of the Tunisian revolution) rather than 19th century ideological constructs such as socialism, let alone liberalism. So far at least, the “Arab Spring” has been about freedom (from want, from fear, from mediocrity), not about democracy.

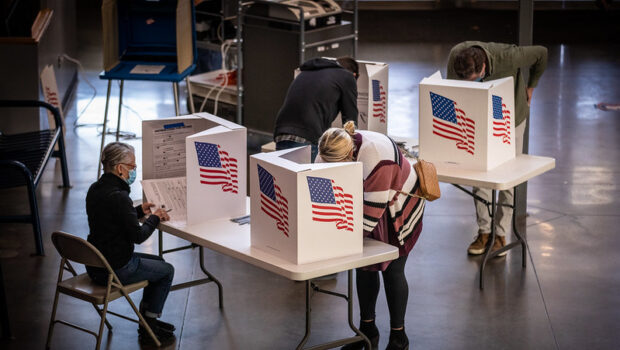

In the absence of great ideological confrontations, the structuring factor of politics is the capacity to understand and adapt to social and cultural change. Indeed, more than ever before, how a regime deals with diversity of politico-cultural forms will be crucial to determine its nature and capacity. An obvious illustration is the use of the Internet and social media as resources for mass mobilizations, most recently in the Arab Middle East. As columnist Thomas Friedman pointed out, Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad can’t handle the brave residents of the small border town of Dara’a (where the uprising against his regime started) and their relentless production of “video, Twitter feeds and Facebook postings of regime atrocities.” Liberation Theology is dead: long life to Liberation Technology! Less dramatic but still noteworthy is the French regulators’ decision to ban the words “Facebook” and “Twitter” from French TV and radio (purportedly, unless those words are used to refer to the companies themselves in news stories). Issues related to immigration (legal and illegal) and cultural diversity is also a key indicator of how good old’ states are capable (or not) to deal with an increasingly globalized and fluid world. Liberal democratic states have challenges of their own, trying to adapt to the increasingly interconnected, wealthy and mobile world of the 21st century. Our system of political participation and representation could use a make over. It is definitely NOT cool or exciting. (Do you remember ever seeing a youngster wearing a t-shirt featuring a picture of John Stewart Mills?) I am not sure the liberal democratic state is better at producing prosperity, security or honesty in government. Where it wins hands down, however, is in its capacity to handle cultural change and diversity.

The Politics of Culture

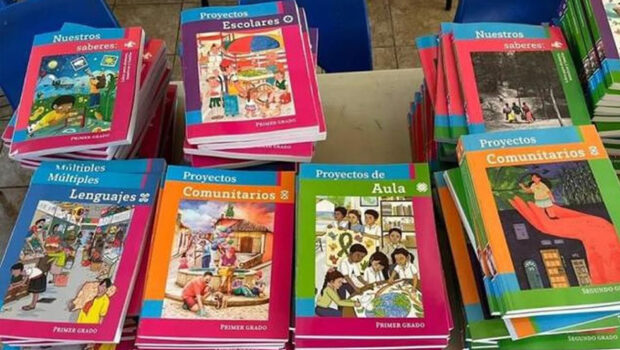

What is at stake is not merely freedom of speech and association, understood primarily as political speech and association, but more broadly, how the state handles the various expressions of freedom. In other words, how it (try to) regulate culture. A priori, culture seems a relatively marginal and non-controversial political issue. Who is against museums, teaching music to the kids, sponsoring theater? In Venezuela, José Antonio Abreu’s “el sistema” (music education for poor children) is probably the only state-sponsored activity championed by the entire cultural and political class. And yet, the reality is that cultural agents fight and compete (notably on the blogosphere) as much as political ones.

Interestingly, for each type of regime one finds a typical cultural policy. Liberal democracies tend to shun them, because for liberals culture belongs to the individual and the private sphere. The best example of this model is the US. But democracies with strong republican and statist tradition, notably France, do have significant cultural policies. In democracies the goal of cultural policy is always to democratize access while fostering creativity and quality, without political interference.

Totalitarian regimes typically considered themselves as the vanguard of genuine cultural revolutions. They sought to unify and control cultural life and artistic production; in fact, the objective was the total control of society. Communist regimes and to a lesser extent Nazism gave some privileges to some artists and intellectuals in exchange for their loyalty and dedication to the party/leader. (Author Miklos Harazti called this their “velvet prison.”) Typically, in their regulation of art, totalitarians wanted control of both the “content” and the “form” of art (remember the Nazi’s attack on so-called “degenerate art”). This type of control would be almost impossible to achieve today. In fact, totalitarianism (a society in which everything is either forbidden or mandatory) is probably unattainable in a postmodern world.

Hybrids have learned to let go on various expressions of freedom, often while retaining a totalitarian core. In Cuba, many visual artists have been authorized to travel and sell their work abroad since the 1980s. Some writers can publish and travel since the 1990s. The state is no longer officially atheist since 1992. Independent bloggers and journalists are harassed, pushed around by government mobs and sometimes imprisoned. But there are dozens of them on the island and they keep pumping out their work. The government almost seems embarrassed to torment outspoken artists directly: see the recent case of painter Pedro Pablo Oliva, expelled from his seat in the provincial legislature but defended by the vice-minister of culture and even, obliquely, by the Communist Youth. It prefers to fabricate charges of “economic crimes” or “corruption,” as some say is currently the case against a number of officials in the Cuban ministry of culture. This is the Chinese government’s official reason for pestering artist and activist Ai Weiwei. In sum, the political logic in Cuba is still totalitarian but the reality is that the country isn’t any more.

In Venezuela, the cultural elite, students and intellectuals oppose Mr. Chávez. The government does not have much lever to impose unanimity the way Cuba did in the early 1960s. Plus Venezuela is not an island, and information is more global than ever before. Only massive repression could produce the kind of unanimity in civil society that would befit the monistic Bolivarian revolution: too high a cost for too limited gain. Political leaders with authoritarian tendencies in Argentina, Equator, Bolivia, and Nicaragua concentrate their fire on the hostile “corporate media,” without ousting them completely. In all these countries capitalism and trade flourish: in fact, Nicaragua is an IMF poster boy.

Again, the Mexican PRI of the twentieth century offers an interesting “model”. It featured some aspects of the totalitarian one-party state, minus its core: it never sought to impose unanimity or to resist social change. Eventually the pluralism of society and culture permeated politics and the PRI-State became a fairly unique Hybrid: what Octavio Paz called a regime “hacia la democracia”. Paz also said, in Hora cumplida (1929-1985), that “Para hacer el elogio del PRI habría que perdirle prestadas a Karl Marx algunas de las expresiones con que hizo el elogio de la burguesía.” For hybrid authoritarian regimes of the twenty-first to become the precursors of more modern and open societies, in tune with their time, studying the recent history of Mexico could save them some very costly mistakes.

Lo que siguió tras la Guerra Fría no fue el “fin de la historia”, como sabemos. Los regímenes autoritarios y semi-autoritarios de todo tipo han coexistido aún con la hegemonía de la democracia liberal –a menudo con notable armonía–, salvo por un añadido más o menos nuevo: llamémosle el Híbrido. Esta forma de régimen autoritario es resultado de la globalización y del cansancio ideológico. Representa a una ideología oficialialista, minimalista y usualmente incongruente que se autodescribe como productora de “resultados” (prosperidad, seguridad, soberanía) más que de sueños telelógicos o utópicos. Así nos recuerda que el “fin de la historia” es, en los hechos, el término de la gran confrontación ideológica pero no el triunfo universal del pensée unique.

Existen dos tipos de Híbridos: el leninismo de mercado y las democracias iliberales. El primero ha tenido su auge en China, Vietnam y cada vez más en Cuba. Según algunos observadores, el llamado “Consenso de Beijing” (monopolio de un solo partido más capitalismo de Estado) va a dominar el siglo XXI. Las “democracias iliberales” están floreciendo en países como Rusia y sus satélites, del mismo modo que en Venezuela, Nicaragua y Ecuador. Tienen en común su fe en el estatismo y los líderes fuertes así como un desdén por los procesos legales. (Existen diferencias importantes entre ellos, obviamente, pero no es el momento de examinarlas.) En países gobernados por Híbridos, el nacionalismo y el populismo han reemplazado a las ideologías políticas “densas” del pasado. Incluso, en un país tan saturado de política como la Venezuela de Chávez, la Revolución es un estilo, un ambiente (un color: rojo) y un recurso retórico, no un sistema coherente de convicciones políticas.

Para los practicantes y los fans de estos Híbridos, la democracia no es ni remotamente tan atractiva como lo que la socióloga estadounidense Theda Skocpol, en su análisis de las revoluciones modernas, llamó “participación popular en la vida política nacional”. En cambio, sí pueden lograr eso los plebiscitos, las elecciones (incluso arregladas), la conexión emocional con el líder, el vínculo rutinario con el partido o el Dios de la Revolución. En términos de política económica, el nombre del juego es capitalismo basado en la exportación, matizado por el patrocinio político (sociolismo).

¡Se podría hasta pensar que el PRI mexicano del siglo XX se adelantó a su época!

La política de hoy es menos “ideológica” de la misma manera que las “nuevas guerras” ya no son manifestaciones de conflictos ideológicos entre las naciones-Estados. También es más desordenada, compleja e impredecible. Las movilizaciones desde abajo, incluso las insurrecciones, expresan un deseo de ganancias prácticas (por ejemplo, alimentos costeables) o valores (“La dignidad antes que el pan” fue el eslogan de la revolución tunecí) en lugar de modelos ideológicos del siglo XIX como el socialismo, ya ni hablar del liberalismo. Por lo menos hasta ahora, la “Primavera Árabe” ha sido sobre libertad (de la necesidad, del miedo, de la mediocridad), no sobre democracia.

A falta de grandes confrontaciones ideológicas, el factor estructural de la política es la capacidad de entender y adaptarse al cambio social y cultural. Ciertamente, ahora más que nunca la manera en que un régimen trata con la diversidad de formas político-culturales es crucial para determinar su naturaleza y su capacidad. Una ilustración obvia es el uso de internet y los medios sociales como recursos para movilizaciones masivas, más recientemente en el Medio Oriente árabe. Como lo señaló el columnista Thomas Friedman, el dictador sirio Bashar al-Assad no puede manejar a los valientes residentes de la pequeña ciudad fronteriza de Dara (donde comenzó el levantamiento en contra de su régimen) y su producción implacable de “video, entradas de Twitter y publicaciones en Facebook sobre las atrocidades del régimen”. La Teología de la Liberación ha muerto: ¡Viva la Tecnología de la Liberación! Menos dramática, pero igualmente notable es la decisión del gobierno francés de prohibir las palabras “Facebook” y “Twitter” de la televisión y la radio francesas (supuestamente, a menos que las palabras se usen para referirse a las compañías mismas en nuevas historias). Los problemas relacionados con la migración (legal e ilegal) y la diversidad cultural también son un indicador clave de qué tan bien los Estados pueden (o no) lidiar con un mundo cada vez más globalizado y fluido. Los Estados liberal-democráticos tienen sus propios retos, tratando de adaptarse al mundo cada vez más interconectado, rico y móvil del siglo XXI. Le vendría bien una remodelación a nuestro sistema de participación y representación política. Definitivamente NO es genial ni emocionante. (¿Recuerdan haber visto alguna vez a un adolescente usar una playera con la imagen de John Stewart Mills?) No estoy seguro de que el Estado liberal-democrático sea mejor para producir prosperidad, seguridad u honestidad en el gobierno. En lo que sí es indudablemente superior es en su capacidad de manejar el cambio y la diversidad culturales.

La política de la cultura

Lo que está en juego no es meramente la libertad de expresión y de asociación, que se entienden básicamente como expresión y asociación políticas, sino cómo el Estado maneja las varias expresiones de libertad en un ámbito más amplio. En otras palabras, cómo regula (o trata de regular) la cultura. A priori, ésta parece un asunto político relativamente marginal y apenas controvertido. ¿Quién está en contra de los museos, de enseñar música a los niños o patrocinar al teatro? En Venezuela, “el sistema” de José Antonio Abreu (educación musical para niños pobres) quizá sea la única actividad patrocinada por el Estado celebrada por toda la clase cultural y política. Sin embargo, la realidad es que los agentes culturales pelean y compiten (notablemente en la blogosfera) tanto como los políticos.

Es interesante que para cada tipo de régimen exista una política cultural típica. Las democracias liberales tienden a evitarlas, porque para los liberales la cultura pertenece a las esferas individuales y privadas. El mejor ejemplo de este modelo son los Estados Unidos. Pero las democracias con tradiciones republicanas y estadistas fuertes, Francia en especial, tienen políticas culturales importantes. En las democracias la meta de la política cultural siempre es democratizar el acceso a la vez que se fomenta la creatividad y la calidad, sin interferencia política.

Los regímenes totalitarios usualmente se han considerado la vanguardia de las revoluciones culturales genuinas. Buscaban unificar y controlar la vida cultural y la producción artística; de hecho, el objetivo era el control total de la sociedad. Los regímenes comunistas y, en menor medida, el nazismo, daban algunos privilegios a artistas e intelectuales a cambio de lealtad y dedicación al partido/líder. (El autor Miklos Harazti llamó a esto su “prisión de terciopelo”). Por lo general, en la regulación del arte los totalitarismos buscan el control tanto del “contenido” como de la “forma” (recordemos el ataque nazi en contra del llamado “arte degenerado”). Tal tipo de control sería casi imposible de lograr hoy en día. De hecho, el totalitarismo (una sociedad en la que todo es obligatorio o prohibido) quizá sea inalcanzable en un mundo posmoderno.

Los Híbridos han aprendido a ser más flexibles en diversas expresiones de libertad, mientras que retienen un núcleo autoritario. Desde los años ochenta en Cuba, a muchos artistas visuales les han concedido permiso para viajar y vender su trabajo en el extranjero. Algunos escritores pueden publicar y viajar desde los noventa. El Estado ya no es ofi- cialmente ateo desde 1992. Los periodistas y bloggers independientes son acosados y amedrentados por turbas del gobierno y a veces son encarcelados; pero hay docenas de ellos en la isla y siguen bombeando su trabajo al mundo. El gobierno parece casi avergonzado de atormentar directamente a los artistas boquisueltos: léase el caso reciente del pintor Pedro Pablo Oliva, expulsado de su escaño en la legislatura provincial, pero defendido por el subsecretario de cultura e, incluso, de soslayo por la Juventud Comunista. Es preferible falsificar cargos de “delitos financieros” o “corrupción”, como dicen algunos que es el caso en contra de varios funcionarios en la Secretaría de Cultura cubana actualmente. Esta es la razón oficial por la que el gobierno chino asedia al artista y activista Ai Weiwei. En resumen, la lógica política en Cuba sigue siendo el totalitarismo, pero la realidad es que el país ya no lo es.

En Venezuela, la élite cultural, los estudiantes e intelectuales se oponen al Sr. Chávez. El gobierno no tiene mucho con qué imponer la unanimidad como lo hizo Cuba a principios de los sesenta. Además, Venezuela no es una isla y la información es más global que nunca. Sólo la represión masiva podría producir el tipo de unanimidad en una sociedad civil que beneficiaría la Revolución bolivariana monista: el costo es demasiado alto para una ganancia muy limitada. Los líderes políticos con tendencias autoritarias en Argentina, Ecuador, Bolivia y Nicaragua concentran su fuego en los “medios corporativos” hostiles, sin derrocarlos por completo. En todos estos países el capitalismo y el comercio florecen: de hecho, Nicaragua es un icono del FMI.

Una vez más, el PRI mexicano del siglo XX ofrece un “modelo” interesante. Tiene algunos aspectos del Estado totalitario y unipartidista, menos su núcleo: jamás buscó imponer la unanimidad ni resistirse al cambio social. Al final el pluralismo de la sociedad y la cultura permeó la política y el Estado-PRI se convirtió en un Híbrido bastante singular: lo que Octavio Paz llamó un régimen “hacia la democracia”. Paz también dijo, en “Hora Cumplida (1929-1985)”, que “Para hacer el elogio del PRI habría que pedirle prestadas a Karl Marx algunas de las expresiones con que hizo el elogio de la burguesía”. Para que los regímenes autoritarios híbridos del siglo XXI se volvieran los precursores de sociedades más modernas y abiertas, en sintonía con su tiempo, estudiar la historia del México reciente podría ahorrarles algunos errores bastante costosos.