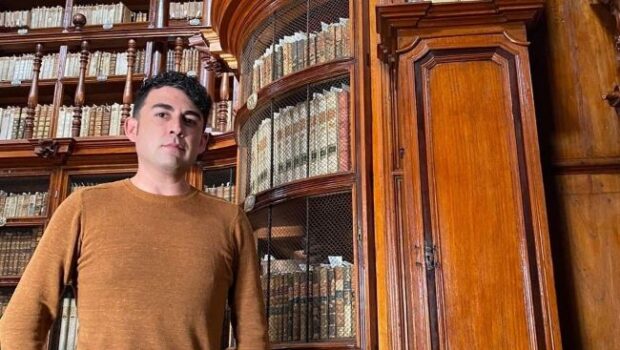

My niece, somewhere near Laredo

Mauricio Ruiz

She came back from the kitchen and put the plate on the counter, poured out more coffee, then dug out her phone and checked her messages. Fine, he thought, you don’t want to look at me, fine. He was grateful, however, for her swiftness and he grabbed his fork and began to eat.

“Not bad,” he murmured, devouring the eggs. When he looked up she was turning away but he caught a glimpse of the letters on her uniform, above her left breast and in script, sown in a fine crimson thread, and he repeated the name to himself. Rita.

She went back through the flapping doors and he noticed the thin waist, the tight peach dress, how it made her buttocks move up and down, like coconut shells adrift in the ocean. He narrowed his eyes and tried to see the shape of her underwear, a vague sense of arousal building up as he stirred on the stool. But he fought it.

She’s probably wearing some of those shaping panties, he thought, the ones that make your ass look firmer, tighter. Women loved that. Yet part of him kept thinking, wondering. How long since he’d been with a woman? He felt old, dejected. He tried to remember someone he’d been intimate with, anyone. He couldn’t remember the face of the convenience store girl who, after many excuses had finally accepted a lift home, their conversation filled with long silences, her hair half-covering her face, and he didn’t force what he knew wasn’t there. He kept his eyes on the road, resigned himself to imagine the unbuttoning of her blouse, smelling the briny sweat of her overworked body. Then, in front of her building she’d leaned over and kissed him briskly on the corner of the mouth before stepping out and disappearing into the depths of the night. The sound wave from the door being shut reverberated through his brain before he realized what had happened. Had it been pity? Curiosity? He still wondered.

He brought the cup to his lips and sipped some coffee. It tasted like burned tires. On the wall, behind the white marble counter, a mirror hung. He held the cup close to his face and watched, almost without blinking. It was inevitable, time, he saw it now; the heavy eyelids, the yellowing teeth. The years, they were unforgiving.

Outside, splitting the prairie, the motorway lay unfurled, vast. Cars streamed past, their wipers on, tail lights gleaming in the distance. Rain filled the pastures.

Harris kept thinking about the moments leading up to the kiss, how his memory of it seemed to be blurry now, with certain elements no longer clear, the name of her street, the creaking sound of her leather jacket, had she said goodbye before stepping out of the car? He was deep in thought when a sound behind him brought him back to the room, to the view of his own face in the mirror, tilted and pale. It was Rita, the sound of her stockings, the friction between her thighs as she walked away. For a moment he tried to picture his routine if he worked there, balancing trays, picking up coins, feeding fries to the cats.

A tanned boy carrying a tray with cups and plates came out of the kitchen. Above his lip, a velvety thin mustache had begun to grow; his arms were bare; a net guarded his hair. He tried his best but the tray seemed to be out to defeat him. Harris watched him.

“Buenos días,” the boy said.

Harris smiled and nodded, then regarded him for a moment while he set the tables. Harris turned his head and stirred his coffee, then gazed at the boy’s image in the mirror and thought of the men squatting, loitering around his house when he was a kid, some of whom he had trouble understanding when they spoke English, and he’d had no patience with them, the same with his mother. For as long as she lived he’d refused to talk to her in Spanish, to listen to her childhood stories from Mexico. As a boy he’d heard how some people talked to her in the streets, called her Latino scum, wetback, and she’d kept her head down, squeezing his hand and saying, Ándale, ya, no mires. Don’t look.

Later, he didn’t want her to pick him up after school; he’d be inside, in the patio, hidden behind a tree, waiting for his father to come instead. Harris looked a lot more like him: the hazel eyes and olive skin, the thinner nose; he’d always insisted on being called by his last name.

He became prickly, even violent, when someone asked if he, too, was Latino. “Speak English,” he’d snap back. The newer immigrants he’d walk away from, ignore them, laugh when they asked if he could speak slower. He’d once beaten his younger brother for calling out to him in public, for saying that a cousin was coming from Mexico. They’d grown distant, estranged, and despite Roberto’s attempts to love his brother, Harris had kept him at bay.

He looked up from his plate and saw Rita behind the counter, holding a pot. “Coffee?”

He nodded.

“Awfully quiet today,” she said.

He kept his eyes on the cup.

“Just call if you need anything, okay?”

When she was gone he turned around. “Casada?” he asked.

The boy laughed. “No. Divorced,” he said, still in Spanish. “Though she has a boyfriend.”

“Does she?”

“And a daughter. My age, I believe.”

Harris nodded. “You believe, yes.” Then he grinned. “So you wouldn’t know her name, or what school she goes to, or anything like that, would you?”

The boy’s cheeks flushed, then they laughed. The boy picked up his tray and said, “Did they give you enough? I can get you more beans, hash browns. What would you like?”

Harris tapped his belly. “I’m fine,” he said, then saw him disappear behind the flapping doors. “Hash browns,” he murmured and shook his head a little, a faint smile beginning to form. He thought of his daughter, Mandy, how she loved that for breakfast. “Amanda, Amanda is my name,” she would correct everyone, including him. It hadn’t been easy, raising her alone. After giving birth, Amanda’s mother had turned her face away and refused to hold the baby; she’d left them without notice. In his building, in the poorest area of town, it had been Dolores, his neighbor, who’d helped him, always open-handed. It seemed like yesterday when he’d heard Amanda call him Da-da, his eyes welling up with tears, and all the pains from work would be gone when he’d find her with Dolores, her little arms waving with joy upon seeing him arrive. Roberto had tried to get closer, be present in Amanda’s life, and Harris hadn’t objected. In his tiny apartment the Sundays were pleasant, even joyful as long as Amanda was near, playing, the center of attention. But after she was put to bed they seemed tense and evasive, almost strangers, while they rearranged crayons and toys and memory cards, Roberto squatting like an old catcher behind home plate, taking his time, always longer than necessary, hoping not to leave again in silence.

Harris hadn’t complained when he first heard Amanda speak in Spanish with Dolores, though he’d intended to. Was he past his insecurities, the shame he felt toward his own mother’s past?

His daughter, his little angel had been the one who tried to redeem him. On her fifth birthday, after Roberto had left, Harris tucked her in and was bending over her to say goodnight when she whispered something.

“That was my birthday wish, Daddy.”

He pretended not to hear her, “Oh, no, no. You’re not supposed to tell me, honey-bun.”

She giggled. “Come on, Daddy, you don’t count. I can tell you everything, like I always do.”

And so she knew, even at five, she knew. She’d wished for her Daddy to make peace with her uncle, to see them laugh and hug each other, the way she did with her teddy bear.

Sitting alone in the diner he thought about Roberto, the news about his possible move to Mexico. A good-hearted woman with two small children, he’d told Harris. She wasn’t interested in coming to America, not really, even if she could see the advantages; so many people in her town receiving cash from relatives, it sometimes made her wonder about her position, but she felt close to her family, the things she had learned to value, which was something she was afraid of losing in America. All this Roberto had mentioned over the phone, more than anything else because of Amanda; that’s what he’d said.

With both elbows on the counter Harris sat hunched. His face looked ashen, his lips dry. He raised his head and brought the coffee to his lips. Behind the counter, Rita was arranging Heinz and Grey Poupon bottles in one of the cupboards. She was watching him.

“You okay?” she asked.

Harris put down the cup and looked at his plate. He stabbed a piece of bacon, the fat, with his fork.

“I’m fine.”

Rita walked over and stood behind the counter, examining him. “Since you came in I’ve been watching you,” she said. “You seem to be thinking about the world coming to an end or something. Not that it’s any of my business, because it’s not, but I can say this, You’re different.”

Harris frowned.

“First thing I have to tell them is, ‘I have a baby at home. Yes, loose skin and belly flab, leave me alone’. It’s a routine, even before I list the specials. Nobody wants to clean diapers. Yes, she’s fifteen and lives two states away with her father. But still, she’s my baby.”

Harris tried not to smile.

“You think I’m joking? Here I get everything. Invitations, obscene remarks about my legs and what not. It never ends. If it weren’t for my boyfriend –” She paused, looked down at his coffee cup. “You married?”

Harris shook his head.

“We’ve been together for ages,” she said. “Or so it feels like. He’s a fireman, tall and strong, though not as handsome as he used to be. He’s lost his hair and most of his tenderness. Truth be told, he’s not the same but hey, show me a woman who doesn’t like a man in a uniform.”

She laughed a little, then coughed. Harris watched her as she blew her nose. There was something about the way she talked with her hands, the long red nails, well cared for, how at ease she seemed to be with her body, voluptuous even in maturity, that he found himself feeling envious, wishing he could embrace his latino self the way she did hers.

Then she said, “But sometimes he drinks and everything changes. For no apparent reason, he goes like.” She snapped her fingers, then sighed. “But I’m not perfect, I know. Nobody’s perfect, right?”

There was silence.

“He shouldn’t treat you like that,” he said.

She gazed at him for a moment. “You know, tomorrow I get off at eleven. Maggie has to leave early, around eight. Her sister’s in the hospital.” She paused. “I could use a ride home. Maybe stop for some tacos on the way?”

She was smiling at him, her head tilted.

Harris looked down and began to stir his coffee.

After a moment she cleared her throat, picked up his plate and the cutlery, the crumpled napkins.

“Do you like pecan pie?” she asked. “Let me get you some pecan pie.”

“Thanks, but – ”

The front door opened and a man with a heavy platform shoe entered. He came in dragging his foot, the right leg abnormally thin.

“Howdy,” he said, to no one in particular. He sat a couple of stools away from Harris.

Rita walked over and put the menu on the counter.

“Take your time,” she said. “Be right back with you.” Then she turned away.

He gaped at her rear as she went back into the kitchen. “Now I’m starving,” he said under his breath. The boy came out carrying clean glasses on his tray; he was singing in Spanish.

“Hey, kid.”

The boy kept singing. He began to put the glasses below the counter.

“Hey, Mexico. Habla inglés?”

The boy froze.

“Café, por favor?” the man said.

The boy nodded, then disappeared behind the doors.

Harris looked at all this, the way the man shook his head a little and muttered something. Then he turned to look at him.

“What do you think of that? It’s not their fault, is it? Living in a country like that. I’d sure as hell do the same, wouldn’t you?”

Harris nodded and tried to smile, a smile that was meant to say, I suppose so but what do I know.

Rita came out and stood behind the counter. She took out her pad and flipped a page. “What will it be?”

The man looked at her breasts as if they were the menu, then said, “Is Rita short for Margarita?”

“No, it isn’t. Anything to eat?”

“What’s the rush?” the man said. His face was unshaven, his pale bluish eyes deeply set, and though his face was rather angular, he might have been perceived as okay looking by some women.

“You seem lonely,” he went on. “I can tell.”

Rita looked more tired than annoyed; she shifted her weight from one leg to the other.

“Why don’t you sit down, have a drink on me.”

“Stop wasting my time,” she said. “You’re not even my type.”

“Not yet. Wait until the lights go out.”

“Is this a joke? Do I have it written on somewhere, come and rub your manhood on my face? Because in case you wondered, I have a boyfriend and I’m happy with him. But that never occurred to you, did it?”

The man just sat there.

“You better find yourself another diner,” she said.

She turned around but the man reached over and grabbed her arm. “Wait up. We’re just talking.”

“Leave her alone,” said Harris.

Rita yanked her arm free and rushed into the kitchen.

“She’s told you she’s not interested,” said Harris. “That should count for something.”

The man slipped down from his chair and walked in small, quick, jagged steps. He did so expertly, the platform-shoe an extension of his body. In a moment he was within arm’s length, smiling, a faint smell of tobacco emanating from his pores.

“Look,” said Harris. “I don’t mean any trouble. The lady there,” and he pointed to where Rita had been. “She has a boyfriend. Let’s not – ” He began to say something but then did not. It was, he knew, an argument he’d already lost.

The boy came rushing in from the kitchen. “La policía, ya viene,” he said to Harris, a bit short of breath. “She’s called them.”

The man walked over to the boy. “What did you just say? Speak English, goddamn it.” He examined him, then laughed. ”Don’t worry, Mexico,” he said. “This is too much for your brain.”

“Leave him alone,” said Harris. “He’s just a dishwasher.”

The man looked at Harris, his eyes slit. “Who the fuck do you think you are?” he said, then dragged his feet up to where Harris stood. “You are just another liberal donkey, aren’t you? Claiming benefits and riding on the sweat of decent Americans.”

Rita appeared at the counter. “Why don’t you sit down?” she said. “Have some coffee, maybe a slice of pie. I can even put it in a doggy-bag for you when the police comes and shows you some manners.”

The man stared at her, then pulled up his shirt and showed the gun tucked in his pants. “What about some respect for a change. Oh man, oh man. Why’s everyone gone so quiet all of a sudden here?”

There was silence. Harris watched him as he smiled, the wrinkles around his eyes and mouth, then he ran a hand through his golden fine hair.

“That’s what I thought,” the man said, as he walked out through the front door.

After the man had gone, Harris sat on his stool, slumped, looking at a photograph he’d taken out of his wallet. It was Roberto, pushing Amanda on a swing.

“Are you all right?” the boy asked.

Harris nodded, half smiling, his eyes still on the picture. “Have you been there?” he asked. “It’s not far from Laredo.”

“Can’t say I have but it looks beautiful. And the girl, she’s having the time of her life.”

“The time of her life,” Harris repeated. “That’s my brother. Do you think we look alike?”

The boy considered this for a moment. “Oh, yeah,” he said. “And your niece, even more so.”

Harris laughed a little, then put the picture back in his wallet.

When he looked up, Rita stood a few feet away, her white apron tossed over her shoulder; she was texting something on her phone.

“When will your daughter come to visit you?”

“What’s that?”

He didn’t say anything more until she put her phone away, walked over to him.

“What did you say about my daughter?”

“I was just thinking.”

“Yes?”

He looked at her for a moment, almost without blinking.

“What?” she said.

“Maybe we can invite him too,” he said, nodding toward the boy. “How would you like that?”

Posted: October 18, 2016 at 9:52 pm