Ode to Tributaries: Mario Reis’s River Paintings

Fernando Castro

The time will come / when I will have to / flow into the oceans, / when I will have to mix my / clear waters with their / murky waters, / when I will have to / silence my luminous song, / when I will have to quiet / my furious cries at / the dawn of day, / when I will have to clear my eyes / with the sea. / The day will come, and in the vast seas, / I will no longer see my / fertile fields, / I will not see my green trees, / my neighboring wind, / my clear sky, / my dark lake, / my sun, my clouds, / I will not see anything, / nothing, / only the immense / blue sky and everything will be dissolved in / a plateau of water, / where another song or poem / will only be a small river that descends, / a rich river that descends to join / my new luminous waters, / my new / extinguished waters. Javier Heraud

The bond between people and rivers is an obvious one. Humans are about 65% water and they need it in order to replenish their bodily fluids. This fact has made rivers the main natural ingredient for the establishment of human settlements and consequently, for the development of civilizations. Not surprisingly, many rivers around the world are considered sacred: the Ganges, the Urubamba, the Nile, and countless others whose native names speak of their vital mission. Rivers descend onto seized lands and flow into shared oceans and seas; they divide as much as they unite us. Rivers also nurture other living organisms. However, many have become polluted by humans to the point that their relationship with the ecosystem has changed from being beneficial to being detrimental.

For over a quarter century German artist Mario Reis has been producing what he calls “nature’s watercolors.” The ambiguity generated by the conjunction of the three terms helps to unravel what these works are about. On the one hand, “nature’s watercolor” means a representation of nature in the medium of water-soluble paint; on the other, it is a “watercolor” made by nature. Whereas, a watercolor is both a type of painting, and the color of water. This multiple entendre is actually a clue to an understanding of Reis’s poetics.

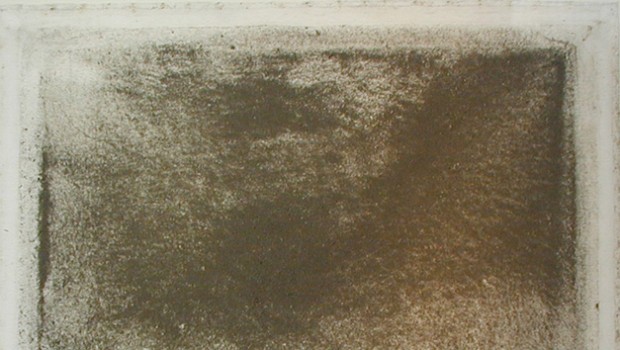

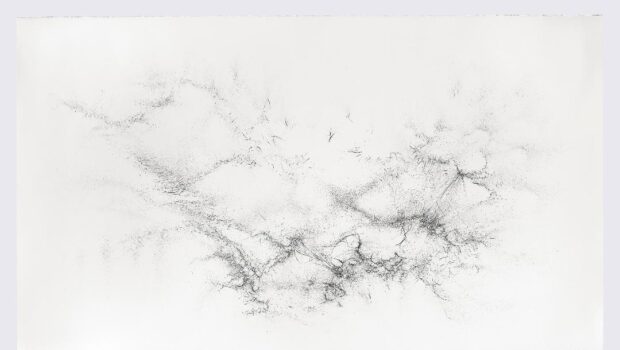

Reis’s technique for making these works is both ritualistic and clinical. He submerges a blank stretched canvas on the shallow waters of riverbeds and waits whatever time is necessary for the fabric to collect sediment at the bottom. He then carefully retrieves it keeping the canvas perfectly horizontal so as not to alter the pattern in which the sediment has accumulated on the fabric. Once the water has sieved through, Reis allows the canvas to dry, detaches the frame and fixes the sediment with a transparent medium. The finished work has the rectangular shape of the frame that cropped it and the color of the sediments. The mineral and/or organic pigments of the sediment collect on the canvas following the rhythm of the waves and currents. Whether the “watercolor” is of the Colorado River or the Mississippi River, its representation is made according to this same algorithm, yet each river painting is quite unique.

Reis judiciously photographs the production site of each river “watercolor” as if he were providing forensic evidence of the connection between a given “watercolor” and a particular river. The ensuing photographic images of the frames in the surrounding landscape have an aesthetic interest in themselves; not unlike the photographs of Christo’s projects, or even more relevantly, those of Andy Goldsworthy’s earthworks.

What collects at the bottom of a river is a good indicator of what its waters hold and what happens upriver –be it a sulfuric volcanic eruption or chemical contamination. So there is something clinical, evidentiary and taxonomic about Reis’s river “watercolors.” Their appearance is as ambiguous as their name. They look like geological samples while at the same time they exhibit the purity of a monochromatic abstract painting. They can hang next to Brice Marden’s Four Seasons, Kazimir Malevich’s White Square, or Yves Klein’s Blue, although the palette of Reis’s river “watercolors” is exclusively the one provided by water and earth: algae greens, iron reds, igneous blacks, sulfuric ochres, and ash whites. More importantly, unlike the aforementioned works whose meaning is open and infinite, Reis’s works are more concrete. The modernist aspiration to reach spirituality through aiming for the void is no longer echoed in Reis’s aesthetics. If any spirituality is reached, it is through the concreteness of the sediment that links a river to the world, and the artwork back to the life of the very people whose river it is. Says Reis, “I had a show in Montana. In that show I had something from each of the 50 states in the U.S. and at the opening I saw ten people standing in front of the work. They didn’t know each other but they were talking, really animated, saying “hey, where are you from? I’m from here,”–pointing at the painting from their state. This interaction is rare. People who don’t know each other were talking, really talking and getting to know each other just because of a piece of art. That’s very rare.”

Curiously, Reis’s “watercolors” represent certain rivers not by depicting them in their liquid splendor but by sampling what is not water in them: their sediment. They show us the connection between water and earth because the sediment is directly dependent on what type of soil the river washes off. There is, however, one aspect of the river paintings that is not representation-by-sampling but rather by something akin to photography. It becomes apparent only when several watercolors of the same river site are arranged in a grid as in Nature Watercolors, Colorado (Colorado River, river sediment on cotton cloth, 1992). The sediment registers the rhythm of the waters on the canvas so that one can almost discern in them reflections of the surface undulations of the river.

It is not the case, by the way, that the sediment that colors the river paintings represents the river by picking out its color, that is to say, the color of its waters. Photographers and seascape painters alike are keenly aware that the color of a body of water is only partially due to the color of the particulates suspended in its liquid and largely due to the color of the sky and light that illuminates it. Thus, a river may change color throughout the day if the sky changes from overcast gray at dawn to light blue at noon.

Neither is it the case that the authorship of these river “watercolors” is to be adjudicated to the river itself as we would to an elephant that had taken up the brush and palette. The river paintings are the makings of nature only in the sense that where the sediments fall on the canvas and what sediment happens to be there, is due to physical and chemical phenomena and not to Reis’s decisions. But the decision to make art this way belongs only to Reis and to his conception of art as collaboration between humans, nature and chance. Reis’s art is conceptual in the sense that it requires the viewer to wonder not only why river sediment has a certain color but also to understand that the point of these works is that they are made in a certain way. Reis stated, “A person can stand in front of my work and tell me ‘I really don’t like it’ or tells me ‘I really love it.’ Both of those are important. Because that means they started thinking. That’s a great thing, to get someone to think.”

Finally, Reis’s river works are–in a very subdued and poetic way–both environmental and social. Their clinical and evidentiary nature may provide evidence of the health and/or unhealthiness of a river. It allows the thoughtful viewer to realize that it is humanity’s responsibility to care for the river’s waters. In Reis’s own words, “We make borders for political reasons. But the water that runs in a river in Japan is the same water that runs in a creek in Mexico. Water is all connected, it moves all around the world (…) and we are like that too. We are the same; people everywhere are the same except for what they pass through.”

Posted: November 3, 2013 at 9:55 am

Hi this cherished one! I would like to declare that this information is remarkable, fantastic published and include close to just about all major infos. I must find far more content this way .