Radio Ambulante

Radio ambulante

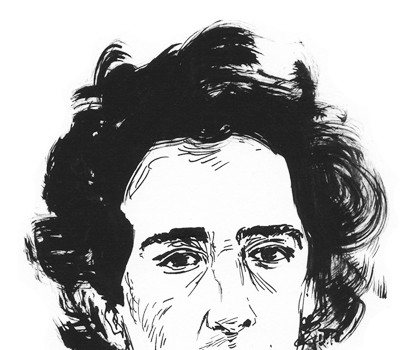

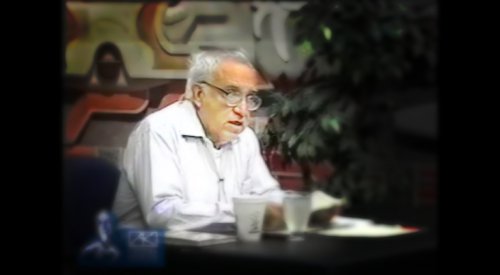

Daniel Alarcón

I first heard of Radio Ambulante while at City Lights Books several months ago, where author Daniel Alarcón mentioned it during a reading. I was intrigued by the idea: a Spanish-language radio program showcasing compelling stories from around Latin America and the United States. As a fan of shows like This American Life and Radiolab, I’ve always taken great radio for granted. But this kind of radio journalism doesn’t really exist in the Spanish-speaking world. Radio Ambulante is changing that. They have built a network of journalists and storytellers from around the Americas and will produce a monthly podcast of stories that can only be told in Spanish. I emailed about the project with Alarcón, now an Executive Producer at Radio Ambulante, and we talked about the art of storytelling and the power of radio.

Daniel Alarcón is author of the story collection War by Candlelight and the novel Lost City Radio. He is Associate Editor of Etiqueta Negra, a quarterly published in his native Lima, Peru, and a Contributing Editor to Granta. He was recently named one of The New Yorker’s 20 under Forty, and his fiction, journalism, and translations have appeared in A Public Space, El País, McSweeney’s, n+1, and Harper’s. Alarcón lives in Oakland, California, where he is a Visiting Scholar at the UC Berkeley Center for Latin American Studies.

***

Nancy Smith: Tell me about Radio Ambulante. How did this project get started?

Daniel Alarcón: In late 2007, I was asked by the BBC to host a documentary about Andean migration to Lima. Naturally, I was intrigued. I come from a radio family, had just published a novel about radio, and the opportunity seemed frankly too good to be true. They sent a great producer from London who took care of the recording, and left me to do the interviews and the narration. I’d just come off a year of book tour, where you read the same text every night, and answer mostly the same questions. I felt my brain had turned off some time in mid-June, but then, doing this radio piece, I suddenly felt like I was thinking again. It was amazing. We spent ten days recording, and I loved every minute of it. But then the audio was mixed down and edited in London without my involvement, and when the final piece was aired, I felt a lot of the most interesting voices had been left out. We’d done interviews in both Spanish and English, and the English speakers got more time. This makes sense from an aesthetic point of view–of course the BBC couldn’t have 45 minutes of voiceovers on the air– it’s just that how do you tell the story of Latin American migration without Spanish speakers? That experience left me thinking about the need for a Spanish language space to tell Latin American stories.

NS: One of your goals is to “tell stories that can only be told in Spanish.” What does this mean for you? There is a lack of this kind of journalism in the Spanish-speaking world, and I also wonder what this means at the level of language and culture.

DA: I’m referring to stories that are by and for Latin Americans, where a certain amount of cultural fluency is expected, where we can delight in the details, the humor, the particularities of speech, of dialects. Something is always lost in translation; we know instinctively that this is the case. A Radio Ambulante story looks at Latin America from the inside.

A lot of attention has been paid in Latin America to the new generation of nonfiction writers, authors like Julio Villanueva Chang, Diego Osorno, Cristóbal Peña, Gabriela Wiener, Leila Guerriero, Cristian Alarcón, among others. These are writers doing important, groundbreaking work. So the talent is there, as is the habit of radio listenership, and what we propose to do is unite the two. We want to have these immensely gifted journalists–men and women who’ve already revitalized the long-form narrative–we want them to tell their stories in sound.

NS: Radio Ambulante brings up some issues of translation. I often wonder if I’m missing anything in a translation. Alejandro Zambra is one of my favorite writers, yet I’ve only read him in English. I’d love to know what goes into translation, especially with fiction, which isn’t just pure content, but style as well. Have you discovered anything in your work that simply can’t be translated?

DA: You’re right, of course: meaning can be usually be approximated, but often by sacrificing style. When I review my translations into Spanish, that’s what I’m most concerned with, reading the sentences aloud in Spanish to make sure they sound the way I want them to. To be honest, I much prefer being translated into Greek or Japanese; in those cases, you have no way of being involved, and no pressure.

Still, I’m a believer in the benefits of translation. It’s a necessity and a privilege–it would be awful to be limited to reading authors who’s work was composed in the languages I happen to have learned.

NS: It looks like you’ll have audio in English at some point too?

DA: Yeah, though we’re still working out how that can be done. We’re producing a bonus track in English for every episode–beginning with a great piece by producer Annie Murphy, but there’s a philosophical as well as aesthetic question that has to be answered: if Radio Ambulante is a Spanish language podcast, what does a Radio Ambulante story in English sound like? How would a Radio Ambulante story in English be different from a similar story produced by This American Life or The Moth or Snap Judgment?

NS: Because Radio Ambulante covers stories from all over Latin America and the United States, I wonder if you see any regional differences in the kinds of stories you produce? Any particular cultural influences that you’ve seen in any of the individual countries? Or are there commonalities?

DA: We begin from the premise that the United States, with 55 million Spanish speakers, is a Latin American country. And to be quite honest, those cultural differences you’re talking about are part of what I find so exciting about this project. I want to hear the diverse accents of Spanish as it is spoken across the Americas. I want to hear those stories that challenge and complicate accepted notions of what Latin America is. We’re working on pieces about the Jewish community in Guatemala, about Mexico City’s best gay soccer team, about a Colombian shaman caught up in a scandal because he couldn’t make it stop raining. The stories we’re looking for are both very specific and completely universal. Of course there will be cultural differences between a story from say, Cuba and a story from Bolivia, but that’s fine. It’s wonderful, in fact.

NS: You mention stories being both very specific and completely universal. The first episode is all about “moving.” Migration, exile, and travel, which seem like completely universal things. Yet we all have very specific, unique stories about moving. How did this theme come together? Will all the episodes have themes?

DA: We wanted to launch with a theme that everyone could understand and relate to, and stories started coming in that were all based on the idea of a move. All of our episodes will have a theme.

NS: I noticed that you’re also featuring fiction writers on the site! This is such a great addition to the journalism.

DA: Thanks! Yeah, it’s something we all agreed is important to the concept of Radio Ambulante. We are journalists, and we are storytellers, and we don’t see that there is a contradiction there. And of course, as a novelist myself, I was committed to the idea of including the voices of the writers I admire. I’m hoping we can someday put out the Radio Ambulante Anthology of Latin American Fiction, in print in both English and Spanish, and as an audio book in Spanish. That would be really exciting, and a fun way to get new voices out there.

NS: Aside from reminding me how rusty my Spanish is, listening to Yuri Herrera read from his novel reminded me how writing is so tied into sound. The element of the human voice feels so essential here, and being able to hear someone speak (as opposed to hearing our own voice in our heads when we read) feels like a more elemental kind of storytelling. More like having a conversation.

DA: That’s what’s great about radio, or at least about the kind of radio we propose to do. It can be almost like a conversation, that intimate, that personal.

NS: You’ve written about radio before in your novel Lost City Radio. What is it about radio that you find compelling? What can radio do that a book can’t do?

DA: Radio is the medium that most closely approximates the experience of reading. As a novelist, I find it very exciting to be able to reach people who might not ever pick up one of my books, either because they can’t afford it (as is often the case in Latin America), or because they just don’t have the habit of reading novels. Radio, or at least the kind of radio we’re proposing to do, can cut through that. It can reach people who would otherwise never hear your work, and of course I find that very notion inspiring. Radio stories are powerful because the human voice is powerful. It has been and will continue to be the most basic element of storytelling. As a novelist (and I should note that working my novel is the first thing I do in the morning and the very last thing I do before I sleep), shifting into this new medium is entirely logical. It’s still narrative, only with different tools.

NS: What have you been reading lately? What Latin American writers should we be reading?

DA: Patricio Pron and Samanta Schweblin of Argentina, Alejandro Zambra and Cristian Alarcón of Chile, Marco Aviles and Gabriela Wiener of Peru, Yuri Herrera, Diego Osorno, and Guadalupe Nettel of Mexico, just to name a few.

Illustration by Joshua Cowan

Traducido al español por Rose Mary Salum

La primera vez que escuché hablar de Radio Ambulante fue en City Light Books, hace algunos meses, cuando el autor, Daniel Alarcón, lo mencionó durante una lectura. Me intrigó la idea: un programa en español presentando historias convincentes de América Latina y los Estados Unidos. Como una devota de los shows This American Life y Radiolab, siempre he dado por un hecho la existencia de buenos programas de radio; pero este tipo de periodismo que se hace en la radio realmente no existe en el mundo hispanoparlante. Radio Ambulante está cambiando eso. Han desarrollado una base de datos con periodistas y narradores de las Américas y producirán mensualmente historias en versión podcast que sólo pueden ser contadas en español. Intercambié correos electrónicos con Alarcón, ahora el productor ejecutivo de Radio Ambulante y hablamos del arte de contar historias y el poder de la radio.

Daniel Alarcón es el autor de la colección War by Candlelight y de la novela Lost City Radio, designada como “la mejor novela del año” por el San Francisco Chronicle y el Wasgington Post, entre otros, y ganadora del Premio Internacional de Literatura 2009 otorgado por La Casa de la Cultura de Berlín. Es editor asociado de Etiqueta Negra, publicación trimestral de su oriunda Lima, Perú, y editor invitado de la revista Granta. Ha sido incluido en la lista de los mejores 20 escritores menores de 40 años del New Yorker y su obra tanto literaria como periodística, así como sus traducciones, han aparecido en A Public Space, El País, McSweeney’s, n+1 y Harper’s. Alarcón vive en Oakland, California, donde es profesor visitante en UC Berkeley y del Centro de Estudios Latinoamericanos.

***

Nancy Smith: Platícanos, ¿cómo empezó Radio Ambulante? Daniel Alarcón: A finales del 2007, recibí la invitación de la BBC para narrar un documental acerca de la migración de los Andes a Lima. Naturalmente, me intrigó la oferta. Provengo de una familia que ha incursionado en la radio y acababa de publicar una novela sobre ésta; la oportunidad, francamente, era muy atractiva. Mandaron un gran productor de Londres, quien se encargó de la filmación y me dejó a mí las entrevistas y la narración. Acababa de terminar el tour de mi libro, en el cual se lee el mismo texto cada noche y respondes en su mayoría a las mismas preguntas. A mediados de junio, sentía que mi cerebro se había apagado, pero al estar haciendo esta pieza en la radio, advertí que estaba trabajando de nuevo. Fue sorprendente. Dedicamos diez días a la grabación y lo disfruté en todo momento. Sin embargo, el audio se editó en Londres sin mi participación y cuando el programa salió al aire, me pareció que habían dejado fuera las voces más interesantes. Habíamos realizado entrevistas en inglés y en español, pero se les dio preferencia a los participantes que hablaron en inglés. Todo esto tiene sentido desde una cierta estética –la BBC no podía llevar al aire 45 minutos de doblaje–, pero ¿cómo cuentas la historia de la migración latinoamericana sin hispanoparlantes? Esta experiencia me dejó pensando en la necesidad de abrir un espacio al español para poder contar historias latinoamericanas.

NS: Uno de tus objetivos es “contar historias que sólo pueden ser dichas en español”. ¿Qué significa esto para ti? Hace falta este tipo de periodismo en el mundo hispanoparlante y también me pregunto qué significado tiene para el idioma y la cultura.

DA: Me refiero a historias que son por y para latinoamericanos, donde una cierta cantidad de afluencia cultural es esperada, donde nos podemos regodear en los detalles, el humor, las particularidades del habla, de los dialectos. Siempre se pierde algo en la traducción, instintivamente sabemos que ese es el caso. Una historia de Radio Ambulante ve a Latinoamérica desde su interior.

En América Latina se ha puesto mucha atención a la nueva generación de narradores como Julio Villanueva, Diego Osorno, Cristóbal Peña, Gabriela Wiener, Leile Guerriero y Cristian Alarcón, entre otros. Son autores haciendo un trabajo y abriendo brechas importantes. El talento existe, así como el hábito de los radioescuchas; nuestra propuesta es reunir a los dos. Queremos tener a estos periodistas dotados –hombres y mujeres que han revitalizado la narrativa–, queremos que cuenten sus historias en audio.

NS: Radio Ambulante presenta algunos conflictos con la traducción. Continuamente me pregunto si no me habré perdido algo en el traslado a otro idioma. Alejandro Zambra es uno de mis escritores favoritos, y aún así sólo lo he leído en inglés. Me encantaría saber qué se va en la traducción, especialmente en la narrativa, que no se limita al contenido sino que también es estilo. ¿A propósito de tu libro, has advertido algo que, sencillamente, no se puede traducir?

DA: Estás en lo correcto, el significado usualmente es una aproximación del contenido y muy a menudo se sacrifica el estilo. Cuando reviso mis traducciones al español, eso es lo que más me preocupa; leo las oraciones en voz alta para asegurarme de que suenan de forma adecuada. Para ser honesto, prefiero ser traducido al griego o al japonés. En esos casos, no tienes forma de involucrarte y ninguna presión.

Aún así creo en los beneficios de la traducción. Es necesaria y es un privilegio –sería terrible limitarse a leer autores cuyo trabajo se realizó en los idiomas que sé.

NS: También incluirás en algún momento el inglés ¿no es así?

DA: Sí, aunque aún estamos viendo cómo puede hacerse de la mejor manera. Estamos produciendo una pista extra en inglés por cada episodio –empezando con una muy buena pieza de la productora Annie Murphy, pero hay una cuestión filosófica y estética que aún falta responder: Si Radio Ambulante es un podcast en español, ¿cómo se escucharía una historia de Radio Ambulante en inglés? En qué se diferenciaría una historia de Radio Ambulante en inglés de una producida por This American Life o The Moth o Snap Judgment?

NS: Si Radio Ambulante cubre historias de toda América Latina y Estados Unidos, me pregunto si observas diferencias regionales en los relatos que produces. ¿has visto influencias culturales en cada país que cubres? ¿o existen más cosas en común?

DA: Partimos de la siguiente premisa: si Estados Unidos tiene 55 millones de hispanoparlantes, entonces es un país latinoamericano.

Para ser honestos, esas diferencias culturales de las que hablas, son parte de lo que encuentro fascinante en este proyecto. Quiero escuchar los distintos acentos del español tal y como se hablan a lo largo de las Américas. Quiero escuchar historias que desafían y complican las nociones típicamente aceptadas de lo que es América Latina. Estamos trabajando con historias de la comunidad judía de Guatemala, sobre el mejor equipo de futbol gay de la ciudad de México o a propósito del escándalo que se armó alrededor de un chamán colombiano que no “paró” la lluvia. Las historias que buscamos son particulares pero, a la vez, universales; claro, siempre habrán diferencias entre una de Cuba y otra de Bolivia. Aunque eso está bien: son hechos maravillosos.

NS: Mencionas que las historias son a la vez específicas y universales. El primer episodio habla de la “mudanza”. Migración, exilio y viajes parecen temas universales. Sin embargo, tenemos algo muy específico, historias únicas sobre la mudanza. ¿Cómo surgió? ¿Todos los episodios serán temáticos?

DA: Queríamos iniciar con temas que todos entendieran y con los que se pudieran relacionar. Comenzaron a llegar crónicas sobre la mudanza. Todos nuestros episodios tratarán sobre un tema.

NS: Pude observar que estás incluyendo escritores en tu sitio web. Es un acierto para el periodismo.

DA: ¡Gracias! Sí, es algo con lo que todos estuvimos de acuerdo y va con el concepto de Radio Ambulante. Somos periodistas y cuentistas y no vemos ninguna contradicción en ello. Y claro, siendo novelista, estaba comprometido a incluir las voces de los escritores que admiro. Espero que algún día podamos publicar la Antología de los cuentistas latinoamericanos de Radio Ambulante en formato bilingüe; y también en audiolibro. Sería una forma divertida de promover voces nuevas.

NS: Escuchar a Yuri Herrera leer su novela no sólo me recordó lo oxidado que está mi español, sino los lazos que existen entre la escritura y el sonido. El elemento de la voz humana es tan esencial. Y al escuchar una lectura (en lugar de oír nuestra voz mental cuando leemos) se “siente” la forma natural de contar un relato. Es como tener una conversación.

DA: Eso es lo magnífico de la radio, o al menos del tipo de radio que estamos proponiendo. Es como una conversación; así de íntima, así de personal.

NS: Ya has escrito sobre la radio con anterioridad en tu novela Lost City Radio. ¿Eso es lo que te atrae? ¿Qué puede hacer la radio que un libro no?

DA: La radio es el medio que más se acerca a la experiencia de la lectura. Como novelista, me entusiasma la idea de llegar hasta esa gente que, de otra manera, nunca tomaría en sus manos un libro mío, ya sea porque no lo puede pagar (como es el caso en América Latina) o porque no tienen el hábito de leer novelas. La radio, o al menos el tipo de radio que estamos proponiendo, puede ser más directo. Alcanza a personas que de otro modo no oirían de tu trabajo; y claro, esa posibilidad muy atractiva. Lo que se cuenta en la radio es fuerte porque la voz humana es poderosa. Ha sido y continuará siendo la forma más elemental de contar una historia. Como novelista ( y debo enfatizar que lo primero que hago en las mañanas, y lo último que hago antes de dormir, es trabajar en mi novela) el traslado hacia este medio es enteramente lógico. Sigue siendo narrativa, sólo que con herramientas distintas.

NS: ¿Qué has estado leyendo últimamente? ¿Qué escritores de América Latina deberíamos estar leyendo?

DA: Patricio Pron y Samanta Schweblin de Argentina, Alejandro Zambra y Cristian Alarcón de Chile, Marco Aviles y Gabriela Wiener de Perú, Yuri Herrera, Diego Osorno y Guadalupe Nettel de México, por nombrar sólo algunos.