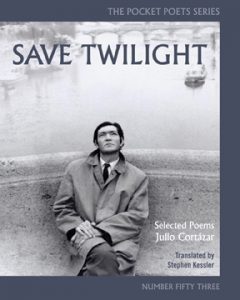

Save Twilight – Poems

Greg Walklin

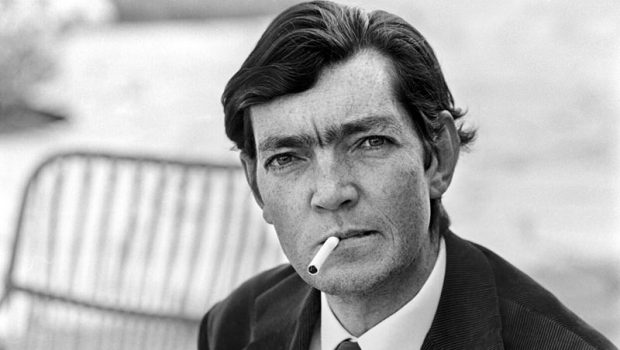

Julio Cortázar

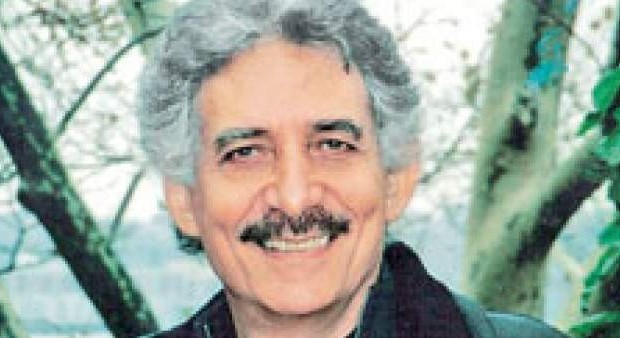

Translated by Stephen Kessler

City Lights Books

Toward the end of his life, Julio Cortázar, living in Paris and surveying the significant trove of verse he had written—to go with all those novels and short stories—decided that their presentation needed an element of randomness. “I never wanted butterflies pinned to a board,” he writes on the subject, in “Save Twilight: Selected Poems.” Despite the opposition of some acquaintances, who claimed he needed some kind of order, Cortázar elected to have “no chronology than that of the heart, no other schedule than that of unplanned encounters.”

So here they are, presented as such, poems interspersed with “prosems” or “peoms” in “Save Twilight” (“Salvo El Crepûsculo”). This new, expanded second bilingual edition from City Lights Books incorporates work that had been cut from the 1997 first edition; the format is a small pocket version with English and Spanish side-by-side, which can be easily carried around. (Pocket poetry editions have an underrated history: when the American poet John Neihardt was a teen, he would carry pocket editions of Tennyson and Browning with him while he weeded beets. They would prove inspirational.)

Cortázar is not known for his verse, but instead for his masterful short stories, and for novels such as “Hopscotch.” Yet for his English-language readers it is a treat to get a more sizeable portion of his verse to go long with the prose. Among the work cut from the first edition—also translated by Stephen Kessler—appearing here is the prosem “For Listening Through Headphones,” a representative example of some of the “improvisational jazzlike prosody” (in the words of Kessler) contained in this volume. There, Cortázar riffs on the experience of listening to music in such a fashion, the private and inscrutable world to others it creates “into a different night, another kind of darkness.” In listening to a Bartók quartet, Cortázar says: “I feel the deepest part of a me a pure connection with that music fulfilling itself in its own time and simultaneously in mine”; mass-transit city-dwellers who spend so much of their days with those small white pearls firmly implanted into their skulls should recognize something. Parts of the piece merge into meter, and then return to prose. “Poetry,” he writes, “is a word heard through invisible headphones.”

Indeed, the potent verses here often feel like the poet whispering in your ear, especially in the lovesick verse—among them “Come Here Alejandra,” “The Brief Love,” and “The Future.” In “The Future,” the narrator talks of the sad times yet to come (“I know full well you won’t be there”) reflecting on an imperfect love—probably doomed from the start, as how it’s now “in the prison where I still hold you.” It will be forgotten altogether, it seems, as everything eventually fades.

Other highlights include “The Brief Love,” which reflects a similar aesthetic, and the caesura-filled “Inflation Lies,” maybe the most gnomic poem here, which expands the romantic focus of “The Future” but still has the best line on the subject: “Love is free you pay at the end.” More of “Inflation Lies,” in fact, is worth quoting at length:

Mirrors are free

but how costly to really look at yourself, and how to see yourself

without it being a pre-stamped postcard

greeting with a view of the leaning

tower.

The rest of these prosems, peoms and poems are filled with such heavy doses of introspection, and even some dashes of the poet’s famous politics. (Cortázar once assigned the rights from a nonfiction book he published to the Sandinistas.) Writing, Cortázar says in a prosem, is “the only fixation given to me to keep me from dissolving in that person who drinks his morning coffee and goes out into the street to start a new day.” From looking at his life, there is no doubt that he wasn’t that sort of person. Born of Argentinian parents in Brussels, Cortázar spent much of his youth in Argentina, but his adulthood in Paris; it was that kind of dislocation that he brought into “Hopscotch,” but which also appears here, such as in “Inflation Lies,” and even more prominently in “The Other”: “Transformation, double enchantment / exposing in me a different self / behind the person I pretend to be.”

Many poems and writings in this collection make it essential for any  fans of Cortázar’s fiction, and a few, such as “To Be Read in the Interrogative,” the most instantly arresting poem here, make it equally accessible to first-time Cortázar readers. That poem begins by asking, “Have you seen / have you truly seen / the snow the stars the felt steps of the breeze.” It continues:

fans of Cortázar’s fiction, and a few, such as “To Be Read in the Interrogative,” the most instantly arresting poem here, make it equally accessible to first-time Cortázar readers. That poem begins by asking, “Have you seen / have you truly seen / the snow the stars the felt steps of the breeze.” It continues:

[H]ave you known

known in every pore of your skin

how your eyes your hands your sex your heart

must be thrown away

must be wept away

must be invented all over again

Part of what makes “To Be Read in the Interrogative” so lovely is Kessler’s translation, which has bestowed a bit more lyricism than was present in the Spanish. When one reads a Cortázar translation, there is an additional layer of interest; Cortázar himself worked as a translator for most of his life, with a day job at UNESCO while also translating literary works by Edgar Allen Poe and Daniel Defoe. Thus, one can read the Spanish and the English translation both as how the translator has translated it and how, perhaps, someone like Cortázar would have written it with a translation already in mind.

Kessler has translated verse from Jorge Luis Borges, Luis Cernuda, and Vicente Aleixandre—and from Pablo Neruda, whose love poems remind one of Cortázar’s missives here—and his work here is both sturdy and creative. In “Law of the Poem,” for example, Kessler has worked out a lyrical rhyme scheme that was absent from the Spanish—although without venturing too far from the original language, rendering line-enders such as “curva del camino” as “curving way” as opposed to a more literal “curved road” or “path,” and the verb “desatar” as “disentwine,” as opposed to a more literal “untie.” Gregory Rabassa, who famously translated Gabriel Garcia Marquez, among others, has observed: “A translation is never finished…it is open and could go on to infinity”—which is precisely what makes bilingual editions like this one so enjoyable; you can pull out your Spanish dictionary and play along, with enough gems in the collection that you could probably land on one by simply picking a spot anywhere in the book.

And that is exactly what you should do: enjoy this collection on the subway or on a walk by pulling out a poem or prosem at random and start reading. Or thumb through and let the heart decide. Either, of course, would have the approval of the author.

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction.

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction.

Posted: November 28, 2016 at 11:34 pm