Spain’s Enticing “Other” Silver Age

Vanessa Fernández-Frey

Maite Zubiaurre,

Cultures of the Erotic in Spain: 1898-1939

Vanderbuilt, 2012.

Cultures of the Erotic in Spain: 1898-1939 is an elegant book with magnificent reproductions. The array of risqué novelette covers, ribald illustrations, racy posters, photographs of nude women in compromising poses and erotic paintings of gay culture are a testament to Maite Zubiaurre’s extensive recovery of an almost forgotten moment in Spanish history. More than a cabinet of erotic curiosities, her study rewrites the prevailing narrative about early twentieth century Spain and presents the other Silver Age—or Edad de plata—in its previously unseen fullest colors. Employing the term sicalipsis, a Spanish word referring to the sensual, she examines the “explosion of erotic artifacts and discourses on sexuality that infused Spanish popular culture,” during the first half of the twentieth century” (5). Delving into early sexology, writings on love and psychoanalysis, as well as salacious novelettes, postcards and magazines, Zubiaurre’s reconstruction of Miguel de Unamuno’s and José Ortega y Gasset’s era reveals a “third” hidden Spain buried under the conventional representation of the country as being either liberal or staunchly conservative. According to Zubiaurre, the culture of erotica and its history was repressed by Francoism and high cultural snobbery as well as neglected by scholars more interested in modernist literature and art. But, countering this disregard, Zubiaurre finds that popular culture’s defiance of conservative cultural norms was crucial for importing modernity into Spain. Unlike conservative and liberal high culture, both intent on preserving Castilian values, this Other Spain, brimming with frivolity and lusty euphoria, openly engaged ongoing contemporary debates regarding patriotism, Spanishness, technology, sexuality and gender, pushing them to unchartered terrains.

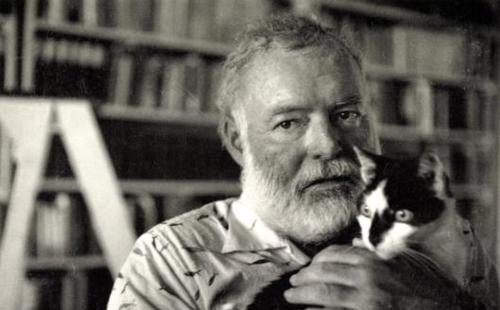

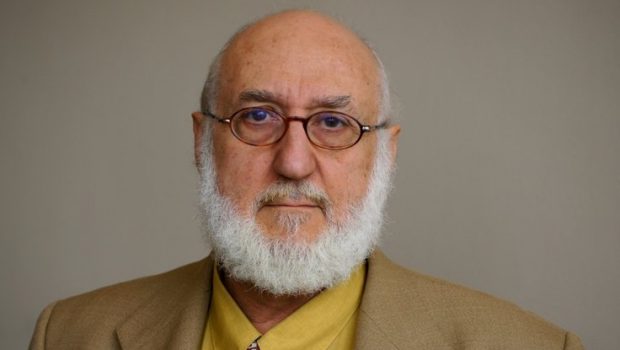

Divided into ten chapters—each organized thematically around high culture’s writings on sexual discourse and paraphernalia used in erotic representations of women such as books, bicycles, typewriters, cigarettes and mantillas—the first section of Zubiaurre’s study typifies her approach. For example, “Spain as Erotic Wunderkammer,” details popular erotica’s importance as a counter movement to dominant modernist and conservative representations of the nation, sexuality and gender. Juxtaposing an image of renowned novelist Miguel de Unamuno with one of Álvaro Retana, a successful sicaliptic author, Zubiaurre illustrates her methodology. On the one hand, bespectacled, distinguished, masculine, austere and erudite, Unamuno’s image visually embodies traditional Castilian values of sexual virtue and a strong sense of españolidad. Such self-fashioning was harnessed by a generation of writers and thinkers bent on rescuing Spain from its post-imperial decline. On the other hand, Álvaro Retana’s more malleable, colorful dress, informal posture, sexual ambiguousness and relaxed demeanor starkly contrast Unamuno’s poise. Retana’s more effeminate, inviting and coquettish glance illustrates popular culture’s unbarred disposition towards sexual variance and acceptance of more modern European trends and fashion.

Zubiaurre’s thematic organization around objects used in erotic illustrations allows her to fully explore how this visual imagery countered specific cultural norms. Women reading books invoked feminist discourse while women on bicycles sanctioned imported modernity. Hybrid representations of barely clad women wearing modern stockings and mantillas were at once patriotic, subversive and anticlerical. Although Zubiaurre concedes that erotica is patriarchal in its objectification of women, she notes that, nevertheless, such depictions desacralized cultural norms and proposed alternatives. Much like this rebellious visual culture, Zubiaurre also reveals that sicaliptic fiction daringly confronted Spain’s anxiety towards modernity, heteronormative sexuality and shifting gender roles, topics consciously ignored by high modernism. Indeed, her inclusion of this genre as worthy of critical attention dramatically rewrites canonical Silver Age literary history. Zubiaurre’s exhaustive study of popular erotica’s importance as a counterculture in Spanish history is a significant contribution to Peninsular literary, cultural and visual studies. An engrossing tour through the tantalizing visual and literary culture of an era, Maite Zubiaurre’s Cultures of the Erotic in Spain: 1898-1939 will certainly reshape how scholars understand the first half of the Spanish twentieth century.

Posted: September 14, 2012 at 4:10 pm