The Boundary between Fact and Likelihood: Darío Robleto at the Menil Collection

Fernando Castro R

The lobby and main hallways of the Menil Collection were packed with people waiting to witness the conversation between Texas artist Dario Robleto and Ann Druyan. Producer of the PBS documentary series Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey, Druyanis also the widow of Carl Sagan. Their conversation was about the Golden Record, a 12-inch gold-plated copper phonograph disk containing sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth. In 1977 it was sent on board space vessel Voyager I to the outer confines of our solar system and beyond. On September 13th, 2013, Voyager I left the solar system and entered interstellar space while still carrying its precious cargo. The Druyan/Robleto dialogue revealed a covert action that changed the Golden Recordproject and that bears directly on the exhibit The Boundary of Life Is Quietly Crossed at the Menil Collection.

Druyan and Sagan were instrumental in making the selections for the Golden Record: sounds and images of thunder, whales, a nursing mother, waves breaking, music by Mozart, Chuck Berry, et al, and 55 greetings in different languages from people around the world, etcetera. Druyan included a couple of personal tracks that were of a more personal nature: her EEG and EKG recorded as she felt her love for Carl. Will that recorded data be sufficient to allow beings more intelligent than we are to reconstruct the feeling of love?

Several assumptions are implicit in the hope that an emotion such as love can be reproduced from the data inscribed in the record, as Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is reproduced by a Bang-Olufsen stylus running through its grooves. In philosophy of the mind the thesis that conscious experience can be accounted for by the physical interactions of neurons, or even molecules, is called physicalism. In the Cartesian dichotomy, res cogitans (mind) and res extensa (body) are ontologically different. Physicalists deny that the mind is a separate entity because they claim it can be fully accounted for by bodily functions. Descartes himself sought a meeting point between the mind and the body in the pineal gland; but otherwise believed both were ontologically exclusive, and irreducible to one another.

The Golden Record is one of those things Robleto would probably like to have made. Like many objects he actually has created, a bystander would probably be skeptical about what it claims to contain, until he/she plays it. The Boundary of Life Is Quietly Crossed is filled with objects such as records, books, daguerreotypes, whale ear-bones, etc., whose authenticity and contents are plausible but may not all be entirely factual. The themes of the exhibit are both benchmarks and challenges from the history of science and technology: the brain, the human heart, the cosmos, and the organisms that live in the depths of the ocean. It is a domain of exploration that encompasses both the infinite and the intimate: the vastness of space, the relationship between mind and brain (terms which Robleto uses enthusiastically and interchangeably). Some of these themes are conspicuously connected, while others require some guidance. Robleto has used recording as a common thread. Do the fossilized whale ear bones hold a record of cetacean conversations across the oceans floors?

Robleto belongs to that rare breed of conceptual artists who are also exquisite craftsmen. His skill is such that one might assume some works actually crafted by him are found objects or readymades (certain books, for example). Secondly, Robleto is also an artist with a strong left brain hemisphere, judging by his ability to use language in order to suggest, persuade and intrigue. At times the very description of the materials of his works constitutes a poetic text. Take Vatican Radio (a work not included in the current exhibit), which I first saw at the Whitney Biennial. Its wall text reads, “Antique Radio: Cast and carved bone charcoal and melted vinyl records of U.S. presidents addressing or declaring war, sulfur, dehydrated bone calcium, cold cast zinc, silver and nickel, melted bullet lead, pigments, dirt, rust, water extendable resin, typeset, speaker. Soundtrack: Loop of the radio broadcast of the first number being called in the draft lottery of W.W. II (October 29th, 1940), Marvin Gaye’s “Sexual Healing,” church bells and choirs. 20” x 15 ½” x 10”.”The viewer may rightfully ask, “Really?” —but at his own risk.

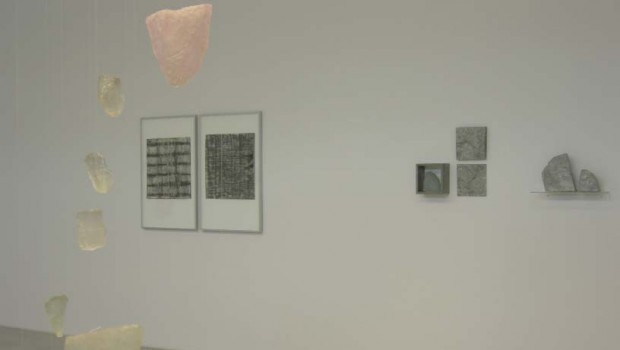

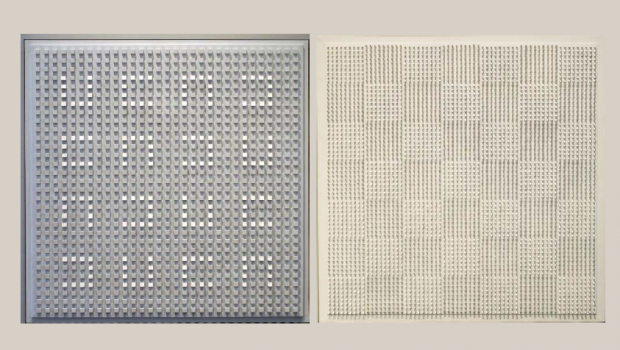

The exhibit at the Menil was structured around three window displays, a stand-alone glass case (“Fossilhood Is Not Our Forever”), and a wooden table (“Things Placed In the Sea, Become the Sea”). The displays are the same kind the museum uses to show objects from its archaeological collection, or even the assortment of things that fascinated Surrealist artists in its “Room of Wonders.” This mode of exhibition contributes to making whatever is contained in them more document-like, and yet more subject to scrutiny. Robleto’s first showcase is titledMachines for Observing Emotions. It is also the title of a chapter in the book The Physiology of Faith and Fear that contains a bit of the little-known history of the heartbeat and the brain pulse. It is a hardcover book printed on vintage paper with the fonts appropriate to the 19th century. As conceptual art, it juggles materiality and content, verisimilitude and factuality. The work consists as much of the stories contained therein as the glue, paper and ink that compose it, the hand that put it all together and the mind that conceived it.

Indeed, the exhibit includes a whole gamut of “books” classified as sculptures, some historical, some factitious and/or fictitious, that hinge upon 19thcentury efforts to observe emotions through ingenious contraptions that record heartbeats and brain pulses. Like the 1877 story of Bertino, an unfortunate man whose skull was cracked by a falling brick which left an opening large enough to observe his “brain’s heartbeats under various stimuli.” The viewer is teased by books qua objects of art that he/she is unable to open: Emotionology (19th Century Graphs of Blushes), Tears That Can Never Rust Vol. I., An Unknown History of the Human Heartbeat, The Lost History of the First Encounter of a Poet and a Stethoscope, Hearts Succumb to Babel: Early Tracings of Lovelorn Heartbeat, The Material Basis of Emotion, etc. A section of the latter reads,“Till the present day no one can imagine how the molecules of the blood penetrate the mass of cerebral cells and become part of consciousness and neither do we know how from the joint life of single cells, something can arise which represents consciousness and sensitivity. And still we persist.” A mystery that also persists.

Michelle White, the curator of the exhibit and Robleto have intermingled objects from the Menil Collection with the artist’s own work. One of the most appropriate is from a documentary by Roberto Rossellini titled Science (1973). During a brief stay in Houston, Rossellini became fascinated with cardiological research and practice, and did a film about it. A second section titled “An Unknown History of the Human Heartbeat” holds recordings of the heartbeat under different circumstances, the most remarkable of which is the humming of a beat-less artificial heart that was implanted for the first time in Craig Lewis, a 55-year-old Texan in 2011. The patient was able to live for only five weeks after the surgery, but the technology changed the paradigm for artificial heart design. Moreover, it defied some of our dearest beliefs about the heart, like its pulse as proof of our being alive, our taking emotions “to heart,” etc. Robleto’s recording of the beat-less heart’s humming takes us back to the Golden Record, and leads us to question Aristotle’s belief that the heart is the seat of emotions, or even to finding consciousness in the brain; then forward again to our so-called “singularity” —the point at which we as humans will transcend our biology. Will consciousness, even our consciousness, ever possess a material basis other than our brains? The latter is perhaps the most salient and important issue prompted by the exhibit The Boundary of Life Is Quietly Crossed.*

*Dario Robleto’s exhibit The Boundary of Life Is Quietly Crossed was shown at the Menil Collection from August 16th, 2014 to January 4th, 2015. The reader may view his works at www.dariorobleto.com.

Fernando Castro is an artist, critic and curator. He studied philosophy at Rice University as a Fulbright scholar. He is a member of the art board of FotoFest and of the advisory board of the Houston Center for Photoography. He is a contributing editor of Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal, and Spot. Last year he delivered the lecture “Elian” at the University of Cambridge, England.

Fernando Castro is an artist, critic and curator. He studied philosophy at Rice University as a Fulbright scholar. He is a member of the art board of FotoFest and of the advisory board of the Houston Center for Photoography. He is a contributing editor of Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal, and Spot. Last year he delivered the lecture “Elian” at the University of Cambridge, England.

Posted: April 19, 2015 at 4:37 pm

Great job Fernando! Hope all is well for you, take care.

John Zotos