The Female Cacique

María Teresa Fernández Acevez

In this abridged excerpt of her book Mujeres en el cambio social del siglo XX mexicano (Siglo XXI, 2014), recently awarded the prestigious Premio Clavijero for its contribution to Mexican historiography, Fernández Acevez proposes the recovery of five abandoned figures of women activists she describes as key to the broad social changes wrought in 20th century Mexico, before and after the 1910 Revolution.

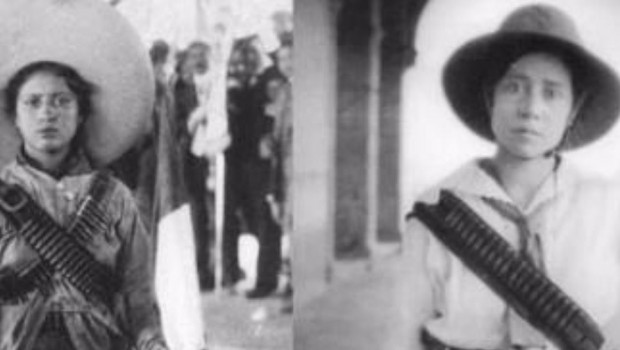

The revolutionary and the political aspects of men have been commemorated and preserved because they showcase their masculinity, whereas the feminine in politics has been forgotten or silenced because it upsets both the reigning social order and gender identities. And yet, women from the working and middle classes resorted to militant and combative representations of femininity in order to garner support and mobilize their sisters. Through these campaigns—educational, rural, electoral, labor, health, and suffragist—they acted decisively to take control of their visual identity, going beyond the female stereotypes endorsed by the Church and the State; occasionally, they became masculinized or were no longer considered to be “traditional women.” Belén de Sárraga Hernández (1872-1950), Atala Apodaca Anaya (1884-1977), María Arcelia Díaz (1896-1939), María Guadalupe Martínez Villanueva (1906-2002), and Guadalupe Urzúa Flores (1912-2004) all fashioned complex representations that confronted traditional stereotypes; they appropriated alternative, transnational imagery (“the mother,” “the angel of the hearth,” “the modern woman,” and “the modern girl”), tailoring it to their own circumstances and careers. Along the way, they changed the public sphere and launched the transformation of the role of women in society, politics, and the workforce.

Categories both theoretical and methodological as well as studies on gender, politics, power, and citizenship in Mexico and Latin America have provided us with a decentralized and regional vision of gender, the State, and power relations, permitting an analysis of the social constructions of gender, caciquismo and citizenship.[1] I chose to analyze these constructions because the cases of Díaz, Martínez, and Urzúa discussed in my book are strongly linked to the political praxis of the cacique in 20th-century Mexico. There is wealth of historiography about caciquismo that characterizes this particular figure as a strongman whose authority stems from informal sources; someone who holds personal and arbitrary political power in a region or location because he has succeeded in mediating with political, economic, social, and cultural structures as well as his own base. Sometimes he wields power through violence in order to dominate; on other occasions he employs more paternalist, clientelist means. The cacique succeeds in controlling wealth, honor, political positions, and political power. He is sustained by hardworking, dependent, close-knit networks built on backscratching and friendship. Likewise, he is considered to be a political and cultural go-between by his superiors and subordinates, because he has successfully articulated different political cultures and created connections between these differences. He is obliged to show his superiors obedience, providing them with information and political support, whereas his subordinates must be loyal and faithful, ready to fulfill any obligations or tasks they are assigned. These characteristics are assembled above all to explain how caciquismo has acted as an integral part of the Mexican political system. Different studies recur to different categories in order to explain the cacique’s wielding of power: intermediation and political articulation, regional and local politics, control, centralization, patronage, clientelism, influence, legitimacy, authority, and domination. From a traditional gender role perspective, women were apparently unable to perform any of these functions.

Both the masculine origin of the word cacique and the reflections of those who have studied the topic have centered their focus mostly on the role of men. However, in recent times, feminist historians have taken women into account as part of cacique power. The historian Raymond Buve points out that the majority of studies regarding caciques have centered on the 19th and 20th centuries and have neglected to mention that in the colonial era, when there were also indigenous women who inherited and exercised roles as caciques. Nicolás Cárdenas García and Enrique Guerra Manzo have suggested a more balanced analysis “in order to interpret the post-revolutionary State and its ties to local powers, proposing that the use of both integrated and marginalized categories allows us to rethink the way in which some actors, in a shifting context, perceived the political system.”[2] Despite these nuances, the perspective regarding caciquismo tends to maintain and reproduce a “natural” distinction between the different traditional roles in society of men —identified with the public and political arena— and those of women —related to domesticity and the private sphere. Although no study has explicitly expressed why women go unmentioned, it seems evident that they fail to appear because they did not go into “politics,” understood as a field exclusive to men.

In counterbalance, this vision has been refuted by women’s studies, especially from a gender perspective. The pioneering study by Joan Scott regarding the use of gender as a category of analysis has shown us that “politics construct gender and gender constructs politics.”[3] Scott attempts to reach beyond the dichotomies that have dominated Western thinking. Similarly, recent gender studies have criticized political theory because it has failed to include gender relations in its analyses. Gender studies approach the reconceptualization of politics and power from three different angles: 1) when falling back on the concept of power conflicts, one argues in favor of the expansion of the institutional conceptualization of politics to include the family; 2) when invoking the concept of power capacity, one seeks to develop norms within the private sphere as part of an ethical conception of politics, and 3) when referring to pragmatic concept of power, one intends to go beyond the dichotomy of public and private in order to develop a more critical conception of politics. Likewise, this vision sustains that there is no “natural” distinction between public and private; rather, they form part of a continuum. The analysis of women in politics thus examines not only the leaders of organizations, but also those who participate in social and political movements. Different studies have argued that all forms of mobilization lead to a process of politicization.

Studies of citizenship, gender, politics, and power in 20th-century Latin America show that with the emergence of women’s movements, specific demands were made of states: equality under civil, labor, and agrarian legal codes, as well as suffrage. These states sought to regulate gender relations with a variety of laws as women slowly, but surely increased their numbers in state beaurocracy and in official organizations. According to Elizabeth Dore and Maxine Molyneux in their book, Hidden Histories of Gender and the State in Latin America, more recent studies have revealed a silenced history of female activism. The lion’s share of historiography about Latin American women in 20th century politics focuses on the role of middle class women, whereas only recently have the contributions of farmwomen, indigenous women and laborers been recovered.

Joyce Olcott has advanced the analysis of citizenship in Mexico by arguing that from 1917 to 1934, Mexican women brandished three contrasting forms of citizenship previously constructed as masculine: a liberal rhetoric of suffrage, traditional forms of clientelism, and the revolutionary promise of popular mobilization. The Constitution of 1917 incorporated a notion of citizenship that encompassed three activities traditionally considered to be masculine: military service, civic participation, and labor force participation. The participation of women in activities constructed as male triggered a strong reaction, one that revealed the instability of gender roles. This semantic and cultural flux illustrated changing views and practices of gender and of citizenship. Olcott sustains that female activists, by claiming revolutionary citizenship, softened accusations that they were disloyal “malinchistas,” adjusting to the prevailing male ideology in order to appropriate and alter it. She also argues that instead of negotiating revolutionary citizenship through demands based on gender differences, women employed a more generalized strategy of destabilizing the exclusively masculine nature of three cornerstones: military service, wage labor, and civic commitment. Women used these categories to obtain aid and support. The five women featured in my book all recurred at some point in their careers to this triad, thereby complicating the historic analysis of the construction of citizenship in keeping with certain specific historic processes.

In analyses of citizenship, gender, politics, and power additional theoretical tools are employed in order to pinpoint women in politics and to expand political concepts through categories such as empowerment—the process by which the oppressed control their lives through the development of activities and structures in order to increase their participation in issues that affect them directly—, female awareness, and concerns involving gender and maternalism. On one hand, in reactive social movements or those that involve practical gender interests, women accept and reinforce traditional labor divisions. These collective actions are a response to their immediate needs and are formulated by the women themselves. On the other hand, proactive movements or those with strategic gender interests mobilize women in order to radically change gender roles.

The maternalist perspective, for example, takes aim at recounting the contribution of middle class women in the emergence of welfare states (1890-1940) with different competitive discourses —regarding citizenship, class relations, gender differences and national identity. Abundant historiography shows that women often mobilize as mothers and community caretakers. In these mobilizations, they fall back on traditional discourses regarding domesticity and maternity and take them into the public sphere as an indication of just how powerful maternity can be as a form of political identity. Through their actions, women have transformed the discursive and spatial limits of the public and private arenas and, of course, have changed the nature of politics. Some feminist historians have defined maternalism as the arguments that were made so that women could be considered subjects who demanded integrity, autonomy, dignity, a political voice, and to be taken seriously in keeping with what has been called “mother-work.” The debate regarding materialism in the early 20th century in the United States, Europe, and Latin America operates as a discourse on two levels: it extolls the virtues of domesticity while at the same time, legitimizing the public relations of women in politics and in the State, the community, the workplace, and the labor market. Feminist academics coincide in that women have politicized any mobilization they have participated in.

Studies of caciques, not unlike those of women and politics (feminine consciousness, empowerment, gender interests and maternalism) use very different categories of analysis, which in turn leads them to obtain different results. It is worthwhile to emphasize that studies about caciques have been strongly biased, as they have been conceived of solely as a male phenomenon. However, once we have incorporated feminist crticism and the category of gender, the door has been opened toward questioning whether this was indeed solely a phenomenon encountered among men. I do not believe that the concept of cacique should be used to study women in order to consider them as heroines, or to compensate their absence in the political system. On the contrary, I consider the concepts of cacique and gender useful in helping us to elaborate more balanced analyses that recognize the different power relations between men and women in systems of both cacicazgo and politics in general.

That is why in my book, Mujeres en el cambio social en el siglo XX mexicano, I chose to contribute to the understanding of the role of women in the constructions of citizenship, education, power, politics and work in relation to the conflict between the Catholic Church and the State, the 1910 Mexican Revolution, the formation of the new State, the consolidation of corporative institutions, and running for elected office. I have attempted to illustrate the interaction between the historic agency of women on a local, regional, national, and transnational level. I analyze and describe in detail the active participation of women as anti-reelectionists, Maderistas, constitutionalists, “reds”, syndicalists, and leaders of women’s sections of labor unions and political organizations. Based on different trends of thought, through social processes, positions, and struggles, they became involved as women, mothers, or workers in the struggle for secular education, labor rights for workers, and the civil and political rights of women. In doing so, they changed our society.

[1] See the essay by Heather Fowler-Salamini entitled “Género y la Revolución mexicana de 1910.”

[2] Raymond Buve, “Caciquismo: un principio de ejercicio de poder durante varios siglos,” Relaciones XXIV, no. 96, 2003. For a very interesting analysis of widowed indigenous women who acted as caciques in the colonia era, see Josefina Muriel, “Las viudas en el desarrollo de la vida novohispana,” in Viudas en la historia, Manuel Ramos Medina (Ed.), Mexico, Condumex, 2002.

[3] Scott, Gender and the Politics of History, New York: Columbia University Press, 1999, p. 27.

MARÍA TERESA FERNÁNDEZ ACEVES es doctora en historia por la Universidad de Illinois en Chicago. Se desempeña como profesora e investigadora en el CIESAS Occidente desde 2001. Su investigación se centra en la historia del trabajo, la historia de mujeres y de género en México en el siglo XX y archivos y memoria. Autora del libro Mujeres en el cambio social en el siglo XX mexicano, México: CIESAS-Siglo Veintiuno Editores, 2014. Editora junto con Susie Porter, Género en la encrucijada de la historia social y cultural, Zamora, El Colegio de Michoacán, CIESAS, 2016; editora junto con Carmen Ramos Escandón y Susie Porter, Orden social e identidad de género. México siglos XIX y XX, Guadalajara, CIESAS-Universidad de Guadalajara, 2006; Autora junto con Alma Dorantes González, Luisa Gabayet Ortega y Julia Preciado Zamora, Guía de la Colección Independencia y Revolución en la Memoria Ciudadana, México, CIESAS-INAH, 2011.

MARÍA TERESA FERNÁNDEZ ACEVES es doctora en historia por la Universidad de Illinois en Chicago. Se desempeña como profesora e investigadora en el CIESAS Occidente desde 2001. Su investigación se centra en la historia del trabajo, la historia de mujeres y de género en México en el siglo XX y archivos y memoria. Autora del libro Mujeres en el cambio social en el siglo XX mexicano, México: CIESAS-Siglo Veintiuno Editores, 2014. Editora junto con Susie Porter, Género en la encrucijada de la historia social y cultural, Zamora, El Colegio de Michoacán, CIESAS, 2016; editora junto con Carmen Ramos Escandón y Susie Porter, Orden social e identidad de género. México siglos XIX y XX, Guadalajara, CIESAS-Universidad de Guadalajara, 2006; Autora junto con Alma Dorantes González, Luisa Gabayet Ortega y Julia Preciado Zamora, Guía de la Colección Independencia y Revolución en la Memoria Ciudadana, México, CIESAS-INAH, 2011.

Posted: December 2, 2015 at 10:00 pm