The Gelatiere´s Lover

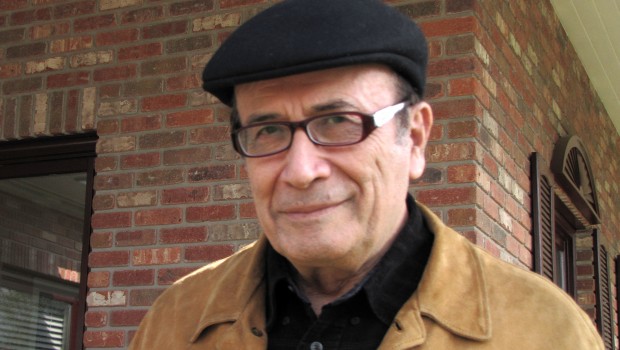

Daniel Zahno

Translated from the German by Janina Joffe

I was born on the eleventh day of the eleventh month of the year. Even though I’m not a numerologist I presume this is no coincidence. My father called me Stuccatore meaning “plasterer”. I have no idea why, but for him I was always the Stuccatore even though I was never interested in the art of plastering. He worked as a boatman on a vaporetto and I was very proud whenever I saw him at the rudder on the Canal Grande. My mother helped out at a hairdresser on the Via Garibaldi in the Sestiere Castello. Both moved to Venice from the mainland in search of happiness when they were young.

In my early childhood this happiness consisted of a tiny two bedroom apartment on the second floor of a reddish brown house on the Rio della Misericordia. It was quiet, had a small garden and a courtyard. A door opened from the laundry room onto this courtyard and while my mother did the washing, I would sit on the stoop or kick a ball against the mouldy walls while the smell of fresh laundry rose through the quad.

Canareggio, where I grew up, was a place where simple people lived. Our neighbours were bricklayers, confectioners and gelatieri. Lawyers, teachers or doctors lived elsewhere. We lived on the farthest edge of Venice, all the way in the north, “fora dal mondo”, outside of the world as even the Venetians would say. There were no gondolas here and tourists seldom strayed to these parts. The only thing that was certain to come here was the water.

We had a small blue boat tied up in front of our house. When Venezia wasn’t playing at the Penzo stadium on weekends we would take the boat out into the lagoon. Other times we would just cruise through the city where my father preferred to head for the Rio del Santissimo which leads underneath the church of Santo Stefano so that he could shout “Pope Hoi” while mass was being read.

That was my childhood–a life alongside water, on water, surrounded by thousands of posts, washed around by waves, a constant rocking and swaying motion. We practically lead a nautical life, deep down we were all sailors and seafarers even though none of us could swim. When I fi rst set foot on the mainland age fi ve, it was a total shock for me. I had assumed that everyone lived the way we did. I saw no appeal whatsoever in driving cars on roads or living in high-rises.

My first walking attempt wasn’t the only thing that proved diffi cult on the mainland. I found school very taxing because I first had to learn how to navigate this completely new terrain–a social Terraferma if you will. My classmates were all bigger, stronger and louder than I was. I was an outsider from the word go since they saw me as a typically spoilt only child. Even the term “only child” upset me–as if it were a disease to grow up alone; as if one couldn’t be normal if one hadn’t grown up with siblings; as if one was scarred irreparably from this experience. It’s not as if the others were labelled with a derogatory term like multiple children. But that didn’t matter to them. What mattered were my many defects. I was far too fragile and sickly. Far too quiet and reserved. Far too small and weak. Far from a stuccatore.

Things only changed for me when the new girl started in our class. Her father was American and her mother from Rome and they had just moved to town from the United States. Since I was the best student in most of my lessons she was sat next to me. I was supposed to look after her and help her out if she fell behind. I was totally unimpressed. I was at the age where a boy wants nothing to do with girls and where one certainly cannot sit next to one of them in class. I feared the mocking I would receive from the other boys–after all it was clearly worse to be called a “girly boy” than an only child.

But the new girl was also an only child. And even though I was sceptical and dismissive at fi rst and my behaviour toward her was clumsy and insecure we became closer every day. She spoke Italian with an American accent which was somehow attractive to me. Her name was Noemi and she was more refi ned and delicate than all the others. Born in Manhattan and raised in Brooklyn she had already seen more of the world than all of us combined. She appeared fragile, nervous and sickly but her beaming eyes and charming smile quickly won me over. I ignored the risk of being bullied as a “girly boy” and did everything I could to help her fi nd her feet as quickly as possible.

She didn’t seem to mind that I was shy and reserved. After the early stages of getting to know each other, I began to sense that she liked me. I think she admired me even though it was unclear why. Maybe she admired me because I was a bit better than the others at mathematics and writing but somehow I don’t think it was anything as banal as that. There was a hidden tenderness in her gestures and glances. I had finally found a friend in class. That this friend happened to be a girl didn’t bother me anymore.

The rest of the grade accepted Noemi reluctantly. She was respected because of her dignifi ed demeanour but some felt inferior and insecure about the fact that she spoke English fluently. She was always friendly but still most found her cool, haughty and arrogant. She wasn’t what a girl from Canareggio should be like. It hurt me that the others didn’t appreciate her the way I did but somehow it bothered me less when I realised that this way she would focus more of her attention on me.

Usually we went home together after school because she lived very close to my house. She visited me sometimes but only when my parents weren’t there. I don’t know if this was the result of her shyness or her intuition. When my mother looked out from the window she never came upstairs with me. Likewise, I was never allowed to go to her house–probably because her mother was usually at home.

I was ill frequently, which my fellow students took as a sure sign of the damage sustained from being and only child and resulted in repeated phone calls to my parents from various teachers. After my tonsils had been removed at the Ospedale Civile I was bedridden for several days. Naturally I had been very afraid before the operation. I remember having my arms and legs strapped to a chair and being shown an orange balloon, the colour of which I had been asked to choose earlier and decided on my second favourite. I tried to reach for the balloon, and as I moved my arm another hand pressed a mask onto my face–gas streamed into my mouth making it nearly impossible to breathe. I panicked and tried to break free thinking they were trying to kill me. The operation was a success.

To my mother’s shame, I threw up in the water taxi on the way back to the Rio della Misericodia. When we arrived at home I still felt nauseous with a very sore throat. My father joked that I should be careful not to end up in the Ospedale degli Incurabili, The Hospice for the Incurable, a place that scared me so much I didn’t even dare walk past it. Somehow the words “incurable” and “only child” were invariably linked in my mind. I expect this was also the case for my classmates, although their reasons were different from mine.

That afternoon, while my father was steering his vaporetto and my mother was working at the hairdressers Noemi visited me. The doctor had recommended I eat a lot of ice cream and so she arrived at my house with two enormous gelati–one was lemon and orange and the other vanilla and stracciatella. Because I loved vanilla more than anything I went straight for that cone. Somehow she had known I wouldn’t be able to resist two of my favourite flavours. I would never have dared to tell her this, but that day I thought she smelled of vanilla too.

I sat upright in my bed and Noemi sat on a chair next to me, both of us very excited about our ice creams. She was happy to see how delighted I was about the vanilla flavour and that her surprise had been such a success. We clutched our gelato cones and looked at the little harbour and colourful boats I had built out of Lego.

Noemi waited a while for her ice cream to begin melting so that its full flavour could expand and only began carefully licking it when it threatened to drip on her skirt. She licked the lemon scoop very slowly, savouring every moment. She treated the ice cream with such care–as if it were fragile. I sat on my bed, devouring my stracciatella scoop and watched her every move. I admired how fully she indulged in the experience. When she had fi nished eating the waffle she licked her fi ngers and wiped her mouth and hands with a little paper napkin. Then she turned toward me with a huge smile.

We seldom ate ice cream at my house. My father didn’t like all the new flavours that were becoming popular these days. And he was convinced that too much ice cream resulted in diarrhoea. That is one of the reasons why I was so totally overjoyed when Noemi turned up at my house with those two giant cones that day.

Dusk began to settle outside. Thick clouds moved across the sky, the Scirocco howled through the streets and I imagined how the boats and ships in the lagoon were being tossed back and forth by the frothy waves. But inside my room on the Rio della Misericordia it was warm and a small lamp created a matt shimmer all around us. Like most times we spent together, Noemi and I didn’t speak much. The song Volare was playing on the radio and Noemi’s smile and the delicious vanilla ice cream had left my spirits so high I really thought I could take off at any moment.

Noemi wore a blue turtleneck sweater that day. Her mid-length blonde hair was pinned up so that she looked completely different to me. She had one leg crossed over the other. Her gaze was lost in the ships in my Lego harbour while Volare kept floating through my bedroom.

“Do you think it’s true what they say–that people who don’t like ice cream are fools?” she asked.

I flinched momentarily. If that were the truth, then my father was a fool. I simply couldn’t let that be.

“I don’t really know” I said. “Where did you hear that anyway?”

“My uncle told me. People who don’t like ice cream are either idiots or barbarians.”

I swallowed. Of course her uncle was right but maybe he should have kept his mouth shut. The thought of my father as a barbarian was inconceivable to me.

“Hmmm…” I mumbled.

“Do you know anyone who doesn’t like ice cream?”

“Could be” I said evasively. I was trapped and looking for a way out. But I couldn’t think of anything and just as I was about to speak everything in my head became jumbled and confused.

“Biters are barbarians” I finally said, pleased that I had managed to come up with a halfway decent comment.

“Biters?”

“Yes, people who don’t slowly lick their gelato but bite into it and swallow it greedily. Like Lucio, for example. Lucio is a barbarian–you can tell from the way he eats his ice cream.”

This appeared to make sense to her.

“Yes, you’re right. Lucio really is a barbarian. And not just when he’s eating ice cream.”

Jokingly I added: “He is a multiple child after all.”

We laughed. We had both been bullied for being only children so many times that a jibe like this felt great.

“Volare” faded in the background and I felt a sharp pain in my throat again.

“Could you imagine having a sister or a brother?” Noemi asked after a moment’s silence.

I didn’t know if I could. I had to let the idea run through my mind first. I had neither a sister nor a brother and consequently didn’t know what it meant to have a sibling at all. It was impossible for me to say something about it because it was impossible for me to even think about it.

“I think I’m getting by ok on my own” I finally said.

“You mean you don’t need anyone to argue with.”

“Exactly”

She looked at me calmly and adjusted her skirt a little.

“Some people think only children don’t learn how to share and are inconsiderate.”

“Only barbarians would say such a thing” I said “and biters.”

We laughed. Her laughter enveloped me in the most wonderful way. It was disarming.

“Didn’t your mother want another child?” she fi- nally asked.

“Could well be” I said. “But may she only had one child in order to spare me from having her experience– my mother had twelve siblings.”

“Twelve siblings!”

“I’m sure she missed out on lots of thing with that many children around. She doesn’t speak about her childhood much and when she does it isn’t particularly positive.”

Noemi nodded. She stared at my Lego harbour again, lost in thought, her eyes lingering on the colourful boats and the model of the Arsenale. Suddenly her expression changed, her face and lips tensed up as if a painful thought was distressing her.

“Do you think parents of only children don’t really love each other?” she asked.

I paused for a moment, unsure of how to answer her.

“Did your uncle tell you that too?”

“No, the mother of a friend in America told me that once. I was so upset I nearly couldn’t breathe anymore. I had to think about how my parents really are like cats and dogs, so different and so argumentative. But then I guess they are also like very close friends.”

I thought about how my parents were around each other and thought it was much the same.

“I don’t think you can set up rules like that” I said defiantly. I was angry at this American mother. She was clearly the mother of a multiple child. “And I don’t understand why your friend’s mother would say such a horrible thing to you.”

Noemi looked down at her hands. Then she placed her right hand on my hot forehead. It was the first time that a female being other than my mother and my aunts had touched me in this way. I could feel something crazy happening inside of me, I was confused but bursting with joy all at the same time. Her hand only rested on my head for maybe three or four seconds but during those few moments a whole new world opened up for me. When Noemi took her hand away I was in a complete mess. I knew that I wanted to go back there, that I was burning to feel her hand again, the warmth of her fingers. At the same time I was strangely sad and nearly began to cry.

My forehead must have been extremely warm, even feverish, because Noemi said I needed to rest and get some sleep. But how could I sleep in the state I was in? She said good-bye and went home.

When I returned to school ten days later, the seat next to mine was empty. At first I thought Noemi was ill but then my teacher told me that her family had unexpectedly returned to New York. I was distraught. Noemi had disappeared just as suddenly has she had arrived in my life. How could this be when I had only just felt this immense joy and the gentle pressure of her hand? Forlornly, I stared in the mirror at the place where her hand had rested on my forehead and locked myself in my room.

For a long time after that I smelled Noemi’s vanilla scent and felt her gentle touch in my daydreams. Her touch was different from every touch I felt before and after that moment. There was only room in my heart for her. But she was gone. It was awful returning to a class full of barbarians and biters without her and from that moment on I was only known as “the girly boy”.

Posted: April 20, 2012 at 7:30 pm