To be a writer in Cuba

Yvon Grenier

The methodology of Leonardo Padura

Soy un escritor, en lo fundamental, de la vida cubana,

y la política no puede estar fuera de esa vida, pues es parte

diaria, activa, penetrante de ella; pero yo la manejo de

manera que sea el lector quien decida hacer las asociaciones

políticas, sin que mis libros se refieran directamente a ella.

De verdad, no la necesito ni me interesa, pero, en cambio,

me interesa muchísimo que mis libros puedan ser leídos

en Cuba y que la gente pueda dialogar con ellos.

Leonardo Padura Cubaencuentro, 19 December 2008

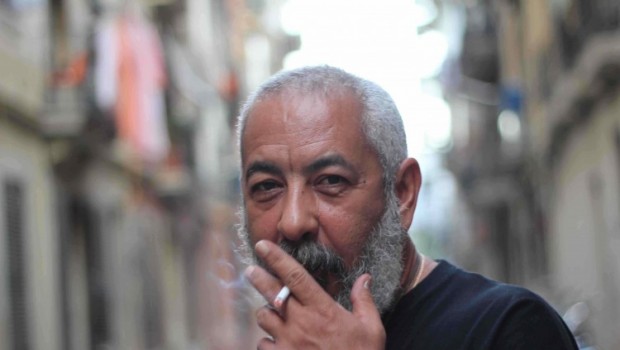

“People think that what I say is a measure of what can or can’t be said in Cuba,” Leonardo Padura once stated in an interview with Jon Lee Anderson. In fact, what he says is a measure of what he—along with some other Cuban writers or artists—is allowed to say in Cuba. It is a privilege, not a right. Lesser authors who don’t enjoy his international fame (and Spanish passport) probably couldn’t have published a book like El hombre que amaba los perros, as he did in 2010, a year after it was edited in Spain by Tusquets. In fact, the book probably wouldn’t have appeared at all in Cuba decades or even years ago, which makes him the beneficiary (and the confirmation) of a recent openness. The government grants Padura some recognition (he won the National Literature Prize in 2012), as well as some privileges commonly bestowed on successful writers and artists: he can travel and publish abroad, and he can accept monetary compensation in foreign currency. But he is kept in a box. His books are nearly impossible to find on the island. The prestigious awards and accolades he is receiving abroad are mostly glossed over by the Cuban media. Finally, his insightful but politically cautious journalism is read all over the world, but not in Cuba (save for a few exceptions).

Numerous times Padura has made clear his desire to live in the house his father built in Mantilla, a working class municipality on the outskirts of Havana. He sometimes signs his articles, “Leonardo Padura, Still in Mantilla.” He also wants to be a “Cuban writer,” and as such, he feels he has “a certain responsibility because our reality is so specific and so hard for many people.” A genuine writer cannot be a mouthpiece for the government. Padura’s success in conciliating these two potentially conflicting ambitions—to be a writer who lives and work in Cuba—is, as John Lee Anderson put it, “a tribute both to his literary achievement and his political agility.” Blogger Yoani Sánchez wrote, “His ‘rarity’ lies fundamentally in having been able to sustain a critical vision of his country, an unvarnished description of the national sphere, without sacrificing the ability to be recognized by the official sectors. The praise comes to him from every direction of the polarized ideological spectrum of the Island, which is a true miracle of letters and of words.” This is why Padura is often seen as a sort of experiment on how to express freedom in a land bereft of freedom of expression.

Itinerary

Padura was born in 1955 in the Havana neighborhood of Mantilla, where he has lived all his life. He studied Hispanic-American literature at the University of Havana from 1975 to 1980, in a time of institutionalization for the regime. Padura has been both a writer and a journalist, two “parallel, almost complementary, apprenticeships.” He worked as a journalist for two publications of the ruling party: El Caimán Barbudo, the monthly supplement of the Communist Party youth branch’s daily, Juventud Rebelde, from 1980 to 1983, and then for the daily itself, from 1983 to 1989. In his reception speech of the National Award, he describes El Caimán Barbudo as “reborn from the ashes of the ‘gray decade’ [meaning the 1970s]”. At El Caimán he “became acquainted with the world and with the figures of Cuban literature of the time,” and “developed a strong sense of generational belonging.” As a matter of fact, at El Caimán he wrote book and theater reviews as well as literary criticism. He rarely fails to mention, perhaps with some pride, that he was thrown out of the monthly for a breach of political orthodoxy. There was no major ideological quarrel, though, only what he remembers as a lot of “foolishness” involving him and other journalists, which cumulatively caused unease on the part of the political leadership vis-à-vis the whole editorial team. This led to a major turnover in the direction of the magazine in June of 1983. Though he often says that he and writers of his generation were under “constant pressure” and experienced “fear”, this was the only time when Padura fell victim to parametración.

In what hardly looks like a demotion compared to the fate of so many writers in Cuba, he was transferred to Juventud Rebelde itself, to be (as he put it) “ideologically reeducated.” He pointed out that “at that time in Cuba, the state was the only employer, and they could send you wherever they liked, and generally you had to comply or look for another job that was invariably worse (as happens to my character Iván in The Man Who Loved Dogs).” This was a blessing in disguise, for this is where his career as a journalist really started. At this daily, he dedicated himself to long-form investigative journalism for the Sunday edition. His contributions consisted of well-crafted essays on pre-revolutionary Cuba (historical themes, historical characters, lost legends of Cuban folklore, as he puts it), with no politics either in content or in style. They could have been published in Bohemia in the 1950s. He remembers that “It was a strange and beautiful period, during which I could write about whatever I wanted—something that isn’t common in the press, and even less so in Cuba. The result was a very literary journalism, based on historical research—a kind of journalism that, by the way, is now considered a classic model in Cuba.” Thankfully, what he wanted to write about was not politically controversial.

Padura contends that during the 1980s, the quality of journalism improved dramatically for about a decade, even becoming a “reference” in Cuba and abroad. He talks about a “breath of fresh air that prevailed at a time that was auspicious for the press in Cuba, but without having achieved full renewal of a media whose fate was sealed by its subordination to the propagandistic interests of the political direction the country had taken, quantitatively and qualitatively.” During a speech at Casa de las Américas in 2012, he makes a different claim: “For a would-be Cuban writer, my work destinations during the decade of the 1980s were the best that I could imagine or choose even today.” He talks often about how beneficial the experience has been for his career as a writer. And yet, he (at least) once admitted “there was still a lot of pressure about what you could and couldn’t say, and there was a member of the Ministry of the Interior who read our work and called us to account if we got out of line.”

All in all, he says very little, and almost nothing critical, about his experience at either of these venues. In essays and interviews he routinely points out that his time at Juventud Rebelde gave him an opportunity to polish his skills as a writer, and taught him the political “rules of the game” in publishing (without explaining what those are). The experience had some indirect impact on the evolution of his consciousness as a Cuban writer and as a member of a “generation” (a favorite theme of his). While he sometimes talks about the constant pressure he and his colleagues felt, in others, he contends that he was free to write what he wanted while working at Juventud Rebelde.

From 1990 to 1995 Padura was Jefe de Redacción at the La Gaceta de Cuba, a high-brow cultural magazine published by the National Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba (UNEAC). In one statement he sounds almost apologetic for accepting the position: “Unless you worked for an official ‘organismo,’ you really couldn’t work at that time.” The UNEAC is officially a “non-governmental organization” but in fact it is evidently government-controlled, like its sister institution, the ICAIC, in the cinematography sphere. It is routinely used to ostracized writers and artists, for instance by expelling them from its ranks, as it did to writer Jesús Díaz and recently to visual artist Tania Bruguera when they crossed a red line. Unlike the daily media (newspapers, radio and television), however, the Gaceta deals with cultural issues and manages to publish moderately critical material from time to time. UNEAC and especially the ICAIC have also been used to protect individual artists or writers, but when the chips are down they work as conveyor belts for the country’s political leadership.

During his time at the Gaceta, the magazine ceased to publish for two years for lack of resources, leaving him with a modest stipend but no real responsibilities and lots of time to write. I found no specific comments of his on the actual experience of publishing in Cuba or the challenges facing a government-controlled writers and artists’ union. Samuel Farber contends that Padura “has abstained from supporting many of the declarations backed by the cultural apparatchnik of the Cuban State to denounce dissidents.” As far as I know, Padura never signed a petition of protest against the government either (such as the so-called Group of Ten’s petition in 1991). In all, he seemed to have kept a low profile at the Gaceta, just as he did at the previous two publications.

Since his experience at Juventud Rebelde, most of his journalism has been destined to foreign readers. Some of them circulated online on the island and a few were reproduced in Espacio Laical, a project of the Father Félix Varela Cultural Center of the Archdiocese of Havana. He participates from time to time in “debates” organized by that Center with other writers or artists. (Note: The word “debate” in Cuba generally means that everybody agrees with each other.) In short, even though he seems risk-averse he is also keen to occupy whatever space is available for public expression. Padura is very astute when dealing with censorship (and self-censorship). And yet, Padura can never feel completely safe and sound in “revolutionary” Cuba. His “freedom” to work within strict parameters, writing novels, screenplays and journalistic articles, is a privilege, not a right.

Freedom

“He tratado a lo largo de todos estos años, y cada vez con

más conciencia e insistencia, de ser un hombre todo

lo libre e independiente que puede ser una persona

en un mundo y en una sociedad como estos en que

vivimos. […] yo lucharé por continuar siendo el mismo,

por pensar con mi cabeza, por ser cada día

un poco más libre.”

Leonardo Padura, Premio Nacional Speech, 2012

Padura is on record denouncing the poverty of Cuban media, the mediocrity of much of what was considered literature during the 1970s and 1980s, and the continuous challenges to finding great books on the island. He talks about the “very serious problem of cultural information in a country with Cuba’s capacity for cultural consumption.” He asks, “When will a Cuban be able to read Roberto Bolaño? When will he be able to read the Japanese writer (Haruki) Murakami or the Swedish writer Henning Mankell?” All of which implicitly raises the key issue of political control of cultural activities and censorship, something he can’t or won’t discuss explicitly in either his essays or his literary work.

In his novels, political problems are more openly mentioned and discussed if they belong to the past, becoming therefore evidence of how things have changed for the better. Hence, in the past, “a compañero was someone capable of handling with skill the castrating art of self-censorship to avoid the insult of being censored.” In a comment on the Obama/Castro accord: “For many years in Cuba, unanimity was promoted as the only alternative. Over the past few years, the possibility of plurality has opened up. While this has not culminated in the existence of political parties (…) it has signaled the possibility of starting to establish different points of view without this meaning that one is an opponent. It is very important to understand this and put it into practice.” When talking about “liberty” in Cuba, Padura points out in an interview that the situation for writers has improved, as a result of their determination to conquer more space: “this space of liberty was no gift, it cost plenty of blood, sweat, and tears.” Again, what Padura can’t or won’t talk about is the political cause of the problems he is examining. In Cuban literature, he wrote, “political realities are submerged, most often remaining unnamed, intentionally alleged.” Which does not preclude the reader from drawing political conclusions. He makes that clear in the following two statements:

My novel Pasado perfecto (1991) took four years to be published in Cuba; Máscaras (1997) was criticized as a work complacent with the “market”… but I insisted, and I increasingly tried to hit rock bottom, going down to the dregs of society and its issues without turning my novels into political documents, although without eluding the political readings that can be made of them, not only about themes such as liberty and totalitarianism but so much more, such as the loss of values and hopes, the drama of exile, the presence of opportunism as a way of life and of betrayal as an attitude…

(1997) was criticized as a work complacent with the “market”… but I insisted, and I increasingly tried to hit rock bottom, going down to the dregs of society and its issues without turning my novels into political documents, although without eluding the political readings that can be made of them, not only about themes such as liberty and totalitarianism but so much more, such as the loss of values and hopes, the drama of exile, the presence of opportunism as a way of life and of betrayal as an attitude…

In my case, the boundaries I have no interest in transgressing can be found in the bogged-down, biased universe of politics. I am not at all attracted to a literature that plays politics because I am a writer, not a politician, nor am I interested in having politicians use my literature as a circus act. And since I am repelled by that universe, I stay clear of it. I am, fundamentally, a writer of Cuban life, and although politics cannot exist outside that life, given that they form a daily, active, penetrating part of it; I handle it in such a way that it is the reader who decides to make the political associations without my books referring directly to them. In truth, I don’t need them, nor am I interested in them; but on the other hand, I am very much interested in having my books read in Cuba, so that people are able to dialogue with them…

This last sentence is important: his books are not easily available in Cuba, but they do circulate. He told me that his books are hard to find for three reasons: first, the economic crisis makes it difficult to publish many books; second, there is a high demand for his books; and third, there is a “lack of will” to publish them. He says that his friends are pressuring the proper cultural authorities to reprint some of his detective stories to honor the twenty-fifth anniversary of the first in the series, Pasado Perfecto (1991), as well as its famous main character, the detective Mario Conde. Although 4,000 copies of his book El hombre que amaba a los perros were published in Cuba, to his knowledge, only 1,400 copies were sold during two public presentations of the book (first 400 copies were made available, then one thousand). Padura doesn’t know what happened to the other copies.

When the journalist John Lee Anderson asked Padura if his novels had ever been censored, he answered, “Fortunately, no.” Regarding the current situation, Padura recently said before a Cuban audience at the Spanish Embassy in Havana: “There is no current policy of what should or should not be published [. . .] I believe enough space has been achieved for almost everything to be published in Cuba.” But according to Anderson, “Onstage, Padura acknowledged that he had frequently suffered from political anxiety: ‘Every time I finish a novel, I say: This is the one they’re not going to let be published.’” Between this and the “almost” of the previous statement, one finds enough qualifying elements to make the first statement (“There is no current policy of what should or should not be published”) ring hollow. “You never know how far you can go,” he also said, adding: “Sometimes it seems as if spaces open and then close again.” With each book, his wife Lucía López commented, “it’s been a matter of pushing the envelope a little further, seeing how far he can go.” Asked if he ever fears retaliation, he responds: “I have done this work from my narrative, but also from my journalism, and I would be lying if I told you that I don’t feel afraid at times. When I finished La novela de mi vida (2002) I thought that I had crossed certain limits of permissibility, but I went ahead anyway. Likewise with La neblina del ayer (2005), and much more so with El hombre que amaba a los perros. But the problem isn’t feeling afraid, which is normal and only human in a society like Cuba’s, but the accumulated experience of what has happened to so many Cuban writers in the past, indeed, with what has happened to me at certain times… The problem, or the solution to the problem, is to overcome the fear. And that is what I have done.”

“In all of my crime novels,” he told Oscar Hijuelos, “from Havana Blue to the one I will publish in Spain this year, Herejes (Heretics), I have always taken a critical view of Cuba’s reality.” The story of detective novels in Cuba is interesting. In 1972, the Ministry of the Interior announced a competition to develop the genre: “The works that are presented will be on police themes and will have a didactic character, serving at the same time as a stimulus to prevention and vigilance over all activities that are antisocial.” The heroes were to be champions of the people, so upright that they refrained from swearing. As Samuel Farber points out, “The first two prizes were awarded in 1973 to two works authored by two MININT [Ministry of Interior] lieutenants, but in subsequent years the prizes were awarded to civilian writers.” In Padura’s novels, on the other hand, the villains are not the usual “counterrevolutionaries”: they are typically “bad apples” of the ruling class. As Anderson puts it, “what Padura does is to find a politically acceptable way to acknowledge the obvious.”

publish in Spain this year, Herejes (Heretics), I have always taken a critical view of Cuba’s reality.” The story of detective novels in Cuba is interesting. In 1972, the Ministry of the Interior announced a competition to develop the genre: “The works that are presented will be on police themes and will have a didactic character, serving at the same time as a stimulus to prevention and vigilance over all activities that are antisocial.” The heroes were to be champions of the people, so upright that they refrained from swearing. As Samuel Farber points out, “The first two prizes were awarded in 1973 to two works authored by two MININT [Ministry of Interior] lieutenants, but in subsequent years the prizes were awarded to civilian writers.” In Padura’s novels, on the other hand, the villains are not the usual “counterrevolutionaries”: they are typically “bad apples” of the ruling class. As Anderson puts it, “what Padura does is to find a politically acceptable way to acknowledge the obvious.”

His most daring novels, from the point of view of publishing within the parameters of Cuba, are the two most recent: El hombre que amaba a los perros (2009), a fictionalized account of Leon Trotsky and his assassin, Ramón Mercader, and Herejes (2013), on prejudices in various times and places. Both are historical novels that concern Cuba obliquely, which a priori is a smart way to handle censorship: it is always easier (and in fact, often encouraged) to talk about faults committed in the past (El hombre) or in any society at any time (Herejes). His previous novels focusing on Cuba tended to think of the past as a cemetery of errors—for instance institutionalized homophobia during the 1970s in Máscaras (1997) —hinting that they may or may not have been rectified today, something the reader has to figure out for herself. As he publicly stated (in Spain): “By my way of understanding, the novel that depends on history to make its artistic trajectory, the writer must take into account that his mission is fulfilled only if his effort is useful in illuminating the present through the examination of experience already accumulated by man in his passage of time, that is to say, historic..” How does El hombre illuminate the present? “My novel has been experienced as a revelation in Cuba, since that history is still unknown here today. The fact that this novel was published in Cuba and that it has won prizes also shows that it is possible now to talk about Stalinism in the Soviet context and in relation to the rest of the world—with respect to the Spanish Civil War, for instance, and, of course, to Cuba.” But the novel does not shed direct light on the relations between Stalinism and Cuba, and he does not make that link clear in interviews either. It does not address the simple question: what was Ramón Mercader (Trotsky’s assassin) doing in Cuba? As we know, Mercader lived in Cuba and worked as an adviser to the Ministry of the Interior. Mercader’s mother, Caridad, worked for seven years in the sixties as civil servant in charge of public relations at the Cuban Embassy in Paris. Padura can’t or won’t connect the dots. None of this takes away the importance and interest of the novel in the Cuban context. Almost anywhere else in the world, this novel would be appreciated primarily for its historical and literary value. There are few other places in the world where condemning Stalin’s assassination of Trotsky “busts myths,” as he said about the book’s impact in Cuba. The novel was clearly dissonant in the Cuban context, and therefore an act of courage on the part of the novelist.

The novel Herejes is more ambitious but it is also several steps further removed from controversies about how Cubans are ruled. As Padura said in September 2013: “To reflect on individual freedom in Cuba, it seemed suitable to me to find parallels that would demonstrate that this phenomenon has been a constant in the history of man…” (my emphasis). His new search for the present gets drawn in the history of humanity, leaving the quest for freedom in today’s Cuba a distant and diluted quest. Thus, he said, “totalitarianism is an ongoing attitude taken by forms of power that may come to be, shall we say, a more full-fledged totalitarianism in determined societies and systems. And individual freedom is a condition or necessity for which we must struggle every day in all societies, even those that proclaim themselves to be more free and open. But, of course, all these readings I make of universal realities part from my Cuban experience and literally, they come and go in Cuba, as is evident to anyone who has read my novels..” Herejes is a celebration of freedom and a condemnation of intolerance in different periods and situations, emphasizing the rather obvious fact that intolerance has been part of the human condition forever (i.e., it is not a specifically Cuban issue). In an interview Padura calls José Martí a “heretic,” (“the intellectual who had committed the heresy of possessing a super talent and human sensitivity”), which arguably defuses the prospect of talking about heresy to critically “highlight the present” in Cuba. If the national hero of Cuba—but also of the regime in place—is a heretic, then possibly Fidel is also fighting for freedom in Cuba. A heretic is a rebel, and officially, in Cuba, rebels are in power, to oppose them is counter-revolutionary, and so on.

The novel Herejes is more ambitious but it is also several steps further removed from controversies about how Cubans are ruled. As Padura said in September 2013: “To reflect on individual freedom in Cuba, it seemed suitable to me to find parallels that would demonstrate that this phenomenon has been a constant in the history of man…” (my emphasis). His new search for the present gets drawn in the history of humanity, leaving the quest for freedom in today’s Cuba a distant and diluted quest. Thus, he said, “totalitarianism is an ongoing attitude taken by forms of power that may come to be, shall we say, a more full-fledged totalitarianism in determined societies and systems. And individual freedom is a condition or necessity for which we must struggle every day in all societies, even those that proclaim themselves to be more free and open. But, of course, all these readings I make of universal realities part from my Cuban experience and literally, they come and go in Cuba, as is evident to anyone who has read my novels..” Herejes is a celebration of freedom and a condemnation of intolerance in different periods and situations, emphasizing the rather obvious fact that intolerance has been part of the human condition forever (i.e., it is not a specifically Cuban issue). In an interview Padura calls José Martí a “heretic,” (“the intellectual who had committed the heresy of possessing a super talent and human sensitivity”), which arguably defuses the prospect of talking about heresy to critically “highlight the present” in Cuba. If the national hero of Cuba—but also of the regime in place—is a heretic, then possibly Fidel is also fighting for freedom in Cuba. A heretic is a rebel, and officially, in Cuba, rebels are in power, to oppose them is counter-revolutionary, and so on.

There is no doubt that both El hombre que amaba a los perros and Herejes can be read as denunciations of the regime and the official history in Cuba, as indeed they are by most readers. But they can also be read as criticism of Stalinist Russia (which has been allowed and to some extent, encouraged in Cuba since the collapse of the USSR) and as an ahistorical celebration of freedom, a value that is officially embraced, in principle, in the 1976 Cuban constitution. His choice to portray Cuban Emos (tattooed and pierced urban youths who defy the revolutionary totem of the ‘new man’) in Herejes is interesting, for it concerns persecution of those who are different socially, not politically, although their apoliticism is in a way a critique of stale utopia and hyper-politicization: “And there they enter the world of urban tribes and more specifically, emos, who would gather at night. You would see them on G Street in Havana. They looked like strange birds, but they were a manifestation of something more profound: the desire to step out of the crowd and create their own identity, which in the end expresses a world-weariness. Cubans need reaffirmation and their most habitual strategy is to keep their distance, to disbelieve. They are heretics.” The political ramifications are clear, but perhaps less so than the psychology of urban youth, making Havana just another city dealing with teenage alienation in the 21st century. Herejes may be read either as a Cuban-style J’accuse or as a mostly apolitical historical novel that confirms Tory prejudices concerning human nature. Padura and the Emos he describes reach the same conclusion: one cannot oppose the political status quo, one can only retreat from it.

In sum, novels like Herejes and El hombre que amaba a los perros are small heresies in the Cuban context, but not predominantly political novels anywhere else. Yet they can be read as condemnations of intolerance and celebration of freedom, with full political implications, which no doubt is a source of concern for the most short-sighted members of the regime. If one can’t call Padura a dissident, it is equally impossible to deny that his work can be read as an invitation to “bust myths” and to foster freedom. Which is why Padura’s books are not readily available, let alone publicly discussed in Cuba.

Journalism

Padura subscribes to the fairly common view in Cuba about literature replacing government-controlled media as a source of information and reflection on the reality of daily life in Cuba, but he can’t bring himself to explain why journalism is so poor. On the other hand, in her foreword to a collection of Padura’s essays mostly published abroad, his wife Lucía López Coll writes that “the writer himself has recognized on more than one occasion that he relies on the practice of journalism to say what he cannot express in his narrative.” In any case, one has to turn to his articles for foreign readers to find Padura’s famed journalism on current events in Cuba.

Most of Padura’s articles on Cuba were commissioned by the Inter Press Service (IPS), an independent and moderately leftist “international communication institution with a global news agency at its core, raising the voices of the South and civil society on issues of development, globalisation, human rights and the environment.” They were published for twenty years under the rubric La esquina de Padura, in many countries but not in Cuba —except illicitly via the internet, or the few times his essays were reproduced in the Catholic magazine Espacio Laical. Padura underlines, defensively, that IPS doesn’t belong to any government and that it pays him very little: about 15 CUCs (or dollars) per article. His pieces vary in genre from “street” journalism (if not very “investigative”) and storytelling to thematic essays on the meaning of history or utopias. A selection of those finally came out in Cuba in three books published in 2005 (Entre dos siglos, La memoria y el olvido, and Un hombre en una isla), all with marginal publishers. One searches in vain for any of these in Cuban bookstores.

Padura explained to Le Monde’s journalist Pablo Paranagua that his journalism is not considered acceptable for publication in Cuba because his “vision of reality is not the one promoted in Cuban media, which prefers propaganda rather than information and analysis.” During the presentation of one of his books featuring a collection of his articles (Un hombre en una isla) at the Feria del Libro in 2014, Padura publicly stated that these were considered unfit for publication in mainstream Cuban newspapers. It begs the question: why?

To begin with, unlike the Panglossian views peddled in Cuban media, his journalism is not triumphalist in tone, quite the opposite. His articles discuss the harsh conditions of living in Cuba, the growing inequalities, problems of corruption, bureaucratic inefficiencies, opaque and top-down decision making, and the bland kowtowing of the media. Padura’s unadorned portrait clashes with official media but it is quite in sync with the dominant literary trend that started during the 1990s, which he characterizes as a “narrative of deconstruction, of ruins, of the apocalypse and marginalization.” Always mindful of boundaries, Padura warns that one can go too far in this direction: “As with any reaction,” he commented, “this one ran the risk of excess and Cuban narrative used to be overflowing with activists, militiamen, abnegated workers and happy farmers, it became overpopulated with prostitutes (jineteras), émigrés (balseros), the corrupt, drug addicts, homosexuals, and a wide variety of marginalized and disenchanted people of all kinds .” In his journalism, Padura alludes to the collapse of the Soviet Union (another rather unusual topic in Cuban media), often referring to it as the “Stalinist” model. It is not always clear if he does that to distinguish it from the better, Leninist original model, i.e., to denounce the deviation from the model rather than the model itself, or because it is a safe way to denounce communism in Cuba. His article entitled “Utopías perdidas, utopías soñadas” (2010) discusses the Katyn massacre and the censorship of Vassili Grossman’s Life and Destiny (a novel that impressed him tremendously). It quotes Orwell and states that totalitarianism is still alive today, though without saying where. He calls for a lucid understanding of past mistakes but remains elusive regarding the lingering effects of those made in Cuba.

I am and will always be convinced that it is useful, indeed urgent, to know and relive in the 21st century the political as well as social and human reasons for the perversion of the marvelous idea that man can live in a society with equality and not only with free health care and education but also the maximum freedom and the maximum of democracy, to make human existence truly more full and whole. The urgency and relevance of this understanding derives from the reality of our world today, battered by economic, ecological, migratory, and religious crises. It is a world that extols its democracy but in which millions of humans suffer from chronic hunger and misery, which makes us consider the necessity of refounding a utopia, a better world, and one doesn’t repeat the mistakes and horrors and that characterised (and ruined) the first attempt, scarring the 20th century.

In this quote, it is typical that as he is becoming more specific with comments on tradeoffs between health care and education on one hand, freedom and democracy on the other, he changes course and reverts to beauty contest platitudes on “a better world” free of hunger and misery. In both his essays and his literary work Padura condemns the most egregious mistakes committed years ago by the “revolution” (one is left to wonder: not by Fidel?): the UMAP (labor camps in the 1960s), the quinquenio gris (the only years—1971-76—officially acknowledged as culturally repressive in the country) and the persecution of homosexuals (until the 1980s). All of this is done in scrupulous compliance with the official parameters: never criticize Fidel and the official narrative about the never-ending revolution; criticize some mistakes made in the past by “bad apples” in the system; and finally, keep criticism well within the cultural field. Fidel Castro is rarely mentioned in his essays and never in his literary work. True, government officials, starting with the Castro brothers, admit mistakes from time to time. But criticism is a rarity in the media, so just to admit the admissible appears edgy.

Padura and Raúl Castro seem to agree on what is the most urgent problem in post-Soviet Cuba: the lethargic economy, still reeling from the post-Soviet crisis, and the persistently low standard of living of the population. He told El País’s columnist Mauricio Vicent that in his view, the worst legacy of Stalinism in Cuba has been its economic model (i.e., not its totalitarian political system, which Padura can’t or won’t discuss.) For Padura, as we saw earlier, the relative prosperity of the subsidized 1980s was a mirage and the contradictions of the socialist economic model were exposed when the socialist bloc fell like a house of cards. Most of Padura’s articles deal with how Cubans can’t afford basic necessities. He talks repeatedly about the weight and inefficiency of the bureaucracy as a particularly negative legacy of the “Stalinist” model. All of his articles on Raúl’s reforms find some faults; typically, they are not fast and comprehensive enough, there is no sufficient information and transparency in the process, and the like. As with many “middle class” Cubans, he seems particularly frustrated by the clumsy policy on sale of private cars. In sum, for him, “The problem is that the great pending task on the Caribbean island is its functioning and internal economic development, something that not even the policies of change carried out in the heat of the ‘updating of the economic model,’ as it has been called, has managed to consolidate.” Still, he remains supportive and cautiously optimistic about the actualización’s chances of success.

On the issue of relations between islanders and exiles, he comes across as generally tolerant and favorable to reconciliation. He berates “fundamentalists at home and abroad” and advocates dialogue and reconciliation. Many of his avowed literary influences squarely belong to the anti-Castro camp (Padilla, Cabrera Infante, Vargas Llosa), or to American literature (Chandler, Chester Himes, Faulkner, Hammett, Hemingway, Salinger, Updike), none of which is officially beyond the pale, of course, but it still gives his intellectual profile an aura of audacity and independence. Since the election of Barack Obama his articles have been cautiously optimistic about the possibility of a rapprochement with the US. He does denounce the “embargo/blockade” (prudently remaining neutral on which term is most appropriate) but does not dwell on this issue and never indulges in anti-Americanism. He emphatically welcomed the Cuba-US December 17th agreement and the rapprochement between the two countries more generally.

Padura is on record saying he is “not a dissident,” adding that he can’t even imagine what he could be dissenting against.” Dissidents do not appear to be part of the “reality” he describes in Cuba, either. He simply never talks about groups or individuals opposed to the Castro regime. Padura wants to preserve his independence on all sides. As he explained to John Lee Anderson, he has “no militancy, not with the Party, nor with la disidencia.” This equal distance between the Party and dissidence means that he must be equally critical of the latter, which may seem absurd, since the Cuban dissidence is minuscule, oppressed and powerless. In fact, he has nothing to gain from the opposition’s “side,” whereas he clearly needs to maintain a good working relationship with the reigning regime. He should therefore at least seem to be more jealous of his independence from the much-maligned opposition.

Padura evidently harbors no illusions about the authoritarian nature of the regime in place. But he seems to believe in the possibility of participation under this system of government. For all of his open-eyes chronicles of day-to-day hardship in the island, his musing on the political situation in Cuba—undoubtedly the central part of the “reality” he professes to describe—is overly cautious. I don’t know the extent to which this results from choices he made freely (like when he wrote uncontroversial pieces for El Caimán Barbudo). Here we touch on the thorny issue of free will in a totalitarian or post-totalitarian environment such as Cuba. What would Cubans say if they could express themselves freely? Whom would they vote for if they had free and fair elections? How different would Padura be as a writer? Arguably, the binary scheme “free will/censorship” doesn’t begin to illuminate the gray zone of self-censorship and path to dependency that prevail under authoritarian systems.

Conclusion

Rather than pushing for more room for expression, Padura’s method seems to be to occupy all the space available without crossing any red lines. This has allowed him to elude the fate that befell so many writers in Cuba. His criticism of many aspects of Cuban society is achieved without directly addressing the political system in Cuba. This method works, in the sense that it provides him with basic guidelines to practice his métier in Cuba. Padura is not an exponent of the “art for art’s sake” viewpoint. He wants to talk about the “reality” in Cuba, but without acting like an activist for change. He cultivates a “practice of social and human introspection that occasionally reaches politics, but that does not part from there..” But one wonders, what happens when it comes to politics, “cuando llega a la política”? The answer is: not much, because he can’t go there and continue living and working in Mantilla. Living and working in Cuba is most valuable not only for him, but also for his readers. In one of his essays entitled “I would like to be Paul Auster,” he complains that he would love not to be constantly asked about politics in his country and how and why he continues to live there. But this is very much his niche: he is widely seen as the best writer in Cuba. He offers us an off-the-beaten path view of a relatively closed society, one that is free of propaganda if not entirely free tout court. No writer could attain global respectability producing a prose laden with official propaganda. By occupying a small but significant critical space in Cuba, Padura becomes more interesting for Cuba observers and more intriguing for students of cultural and literary trends on the island. In this sense, he may be compared to authors and artists who produce somewhat critical material under dictatorial regimes, like Ismael Kadaré (Albania-France) or Murong Xuecon (China) —he is closer, in fact, to the former than the latter.

In sum, Leonardo Padura found a sweet spot that has allowed him to navigate the tumultuous waters of censorship while searching for (and finding) his own voice. He has managed to become, as one observer wrote, “perhaps the foremost chronicler of the island.” Does he (and do his readers) pay too high a price for his privilege to write “from Mantilla”? Would he be more valuable to us, and a better writer, in exile?

References

Anderson, Jon Lee. 2013. “Private Eyes.” The New Yorker. 21 October.

Burnett, Victoria. 2015. “Blurring Boundaries between Art and Activism in Cuba.” The New York Times. 23 January.

Cancio Isla, Wilfredo. 2014. “Leonardo Padura: ‘El problema es imponerse al miedo’.” Digital magazine Café Fuerte. 18 February.

Curet. José. 2013. “‘Herejes,’ la novela más reciente de Leonardo Padura.” Digital magazine 80 grados. 11 October.Farber, Samuel. 2012. “La izquierda y la transición cubana—En diálogo con El hombre que amaba a los perros, de Leonardo Padura” Nueva Sociedad 23 (March-April).

Farber. Samuel. 2014. “Trotsky in Cuba.” Digital magazine Jacobin. (www.jacobinmag.com). March.Hijuelos, Oscar. 2014. “Leonardo Padura.” Digital magazine Bomb no. 126 (Winter).

López Coll, Lucía. 2012. Foreword in Leonardo Padura. Un hombre en una isla, Crónicas, ensayos y obsesiones. Selection by Lucía López Coll and Vivian Lechuga. Santa Clara, Cuba: Ediciones Sed de Belleza.

Padura, Leonardo. 1994. El viaje más largo. Ediciones Unión.

Padura, Leonardo. 2005. Entre dos siglos. Inter Press Service.

Padura, Leonardo. 2008. “Cuba es un país que mira al pasado: De la tetralogía de Mario Conde a ‘El hombre que amaba a los perros'”. Interview with Luis Manuel García. Digital magazine Cubaencuentro. 19 December.Padura, Leonardo. 2009. El hombre que amaba a los perros. Barcelona: Tusquets.

Padura, Leonardo. 2010. “Utopías perdidas, utopías soñadas.” IPS 26 October.

Padura, Leonardo. 2012. Speech, reception of Premio Nacional de Literatura. Reproduced in digital magazine Café fuerte. 18 February 2013.

Padura. Leonardo. 2012. November speech at the Casa de las Américas, Semana de autor. Translated and reproduced as “Writing in Cuba in the Twenty-first Century.” In World Literature Today (www.worldliterature.org). May.

Padura, Leonardo. 2012. La memoria y el olvido. Habana: Editorial Caminos, Centro Martin Luther King, Cuban office of the Inter Press Service and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation.

Padura, Leonardo. 2012. Un hombre en una isla, Crónicas, ensayos y obsesiones. Selection by Lucía López Coll and Vivian Lechuga. Foreword by Lucía López Coll. Santa Clara, Cuba: Ediciones Sed de Belleza.

Padura, Leonardo. 2013. “En Cuba, la herejía expresa necesidad de reafirmación y cansancio histórico.” Interview with Fernando García. In Spanish daily La Vanguardia (www.lavanguardia.com). 22 September.

Padura, Leonardo. 2013. Herejes. Barcelona: Tusquets.

Padura, Leonardo. 2014. “Cuba, la integración y la normalidad.” IPS 14 February.

Padura, Leonardo. 2014. “El instinto de libertad del hombre es invencible.” Speech, reception of X Premio Internacional de Novela Histórica, Ciudad de Zaragoza, 28 May. In digital magazine Café fuerte.

Padura, Leonardo. 2015. Aquello estaba deseando ocurrir. Barcelona: Tusquets.

Padura, Leonardo. 2015. Personal interview. Yvon Grenier. 19 June.

Paranagua, Paulo. 2014. “L’écrivain Leonardo Padura critique la bureaucratie et l’anti-intellectualisme à Cuba.” Paranagua’s blog in Le Monde (America-latina.blog.lemonde.fr.) 22 September.Sánchez, Yoani. 2012. “Leonardo Padura: The Man Who Loved Books.” Digital magazine Huffington Post. 12 January.

Yvon Grenier teaches and writes on Comparative politics, Latin American politics (esp. Cuba, Mexico and Central America), Art /literature and politics, as well as political violence.He is also a Contributing Editor for Literal as well as an occasional political commentator for Radio Canada/CBC. His Twitter is @ygrenier1

Yvon Grenier teaches and writes on Comparative politics, Latin American politics (esp. Cuba, Mexico and Central America), Art /literature and politics, as well as political violence.He is also a Contributing Editor for Literal as well as an occasional political commentator for Radio Canada/CBC. His Twitter is @ygrenier1

Posted: February 1, 2016 at 10:50 pm