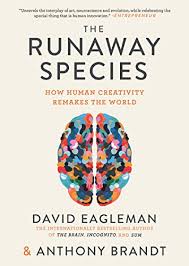

The Runaway Species

Greg Walklin

By Anthony Brandt and David Eagleman

Catapault Books

$28.00

Among the many interesting facts one can learn in reading The Runaway Species, by Anthony Brandt and David Eagleman, is that sea squirts eat their own brains. The invertebrates find a spot to latch onto and, their life quest complete, consume their brains for nutrition. If that seems an apt metaphor for American political life, or the current state of film, or American culture, or whatever has you down, perhaps you should not become too depressed—because humans are wired to find ways out of such messes. As Brandt and Eagleman write, “[o]ur constant itch to combat routine makes creativity a biological mandate.” Brandt and Eagleman have charted this itch in a book that explores the basic ontology of creativity: how it works, what makes it happen, how to spur it and where it may take us.

This is popular science, so it is not meant to dig deep into its subject, but provide something readable and accessible that helps those trying to scratch creative itches—or enjoying seeing the scratches—assemble some kind of picture of others’ imaginary pictures. Brandt and Eagleman describe three “basic routines of the software of invention,” which they categorize as “bending,” “breaking,” and “blending.” Each are supported by numerous examples from the creative and technological arts. For “bending,” they cite Katsushika Hokusai’s myriad depictions of Mount Fuji, and also Monet’s many views of the Rouen Cathedral in Normandy; both artists kept taking the same iconic visuals and reworking them, over and over, to achieve something new and different. Similarly, Seurat employed the technique of “breaking” in his trademark pointillism style—the idea being to deconstruct the form or process of something and create something new from it. “Blending” is an ancient technique that dates at least all the way back to the most famous example cited in this book—the Sphinx.

Of course, the same techniques that allow for expansion in the creative arts also allow for restrictions, such as signal scrambling (bending) that early broadcasters used to ensure potential viewers paid up. Creativity swings both ways: the human mind’s creative power can be used for artistic flourishing, for saving lives—think of the creative problem NASA engineers faced with recharging the Apollo 13 command module’s batteries, famously dramatized in Ron Howard’s film—and authoritarian control. Whatever method of creativity is used, the success of the result, Brandt and Eagleman posit, is still dependent on the culture in which they land. Novelty is no guarantee of success, but a complicated web of history and culture can determine an invention’s success or artwork’s acceptance or popularity. “We live,” the authors write, “in a perpetual tug of war between the predictable and the surprising.”

The issue facing the creative, then, is whether to stay too much with the current mileau or push farther into new territory. On one end was Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge, which was panned by critics at its release but has since grown greatly in reputation; on the other side is Blackberry’s smart phones, which hewed too close to then-extant preferences for physical keyboards, while the virtual keyboard of the iPhone passed them by. These conclusions can feel a bit reductive at times—the Blackberry, for example, failed for many reasons other than its physical keyboard—but the larger points still remain.

The hardcover edition of the book is littered with a lot of rich color pictures, illustrating the various examples the authors cite. These are essential—this is not a book you want to read on Nook or Kindle, or listen to on audiobook, because it benefits greatly from its visuals. At the risk of bringing up a persona non grata in the popular science world, the style here is reminiscent of Jonah Lehrer (at least the good traits of his work!): Brandt and Eagleman have put forth easy-to-read prose that distills concepts down to digestible nuggets, conversational and non-technical. There are no flourishes, but there never need to be. Eagleman is a neuroscientist, while Brandt is a composer, so their professions naturally enable the book to have a dual focus on both the brain’s side of the creative process, and its practical application to people driven to translate those brain waves into painting, music, sculpture, text or anything else.

As for the future, the authors (refreshingly) don’t even try to predict, instead saying it will be unpredictable—that there may even be a time where, for example, even Shakespeare is forgotten. Yet there are plenty of insights in this book for the here and now. The best lesson to be gained from this book, at least for those for whom, in the words of writer Megan O’Rourke, “the only compensatory religion is art,” is a bit of advice from Thomas Edison, quoted here: “When you have exhausted all possibilities, remember this: you haven’t.”

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. Twitter: @gwalklin

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. Twitter: @gwalklin

©Literal Publishing

Posted: April 16, 2018 at 11:12 pm