Mephisto’s Waltz

Greg Walklin

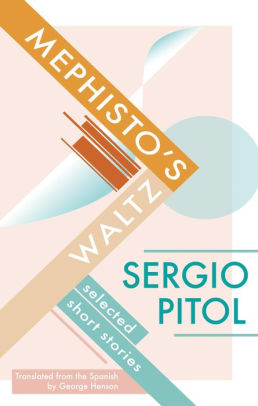

Mephisto’s Waltz

Sergio Pitol

Deep Vellum Press

Sergio Pitol died earlier this year. He left behind celebrated short stories, novels, and nonfiction. A review couldn’t hope to adequately summarize his life, except to say that the word “globetrotter” fit few people better. He lived out in the world, preserved art, and fought for the things he believed in. More than a decade ago, he won the Cervantes Prize, one of the most prestigious literary awards in the world. And yet, despite all of this, not much of his fiction has made its way into English.

Now comes Mephisto’s Waltz, from Deep Vellum Publishing in Dallas, translated by George Henson; the first short story collection of Pitol’s to be published in English. This collection, however, is not simply a translation of “Vals de Mephisto,” which appeared in Spanish in 1984, but a selection of thirteen tales written from the 1950s through the 1990s, picked by Pitol himself before his death. While some individual stories have appeared in translation before, this is a career-spanning collection of the Mexican master in his all M.C. Escher-like complexity. The book generally improves as it goes along—the stories appear chronologically in this volume, so one can see Pitol’s vision sharpening—with the last three indelible pieces: “Mephisto’s Waltz,” “Bukhara Nocturne,” and “The Dark Twin” being both the strongest and most lucid.

In the title story, supposedly Pitol’s favorite, the author displays his ability to weave a story and meta-stories together into brilliant reflexivity. An unnamed woman reads the short story “Mephisto’s Waltz” written by her husband Guillermo. Having fought and separated, they’d come to a “truce” to “know the sober pleasure of being apart.” The story’s sudden publication—”without the slightest warning,” meaning without her having reviewed the draft—she interprets as “a polite way of telling her that things were no longer the same between them.” There follow two stories: the story of the woman and Guillermo, and the story-within-the-story of “Mephisto’s Waltz” (itself titled after four Lizst compositions), in which she cannot help but search, in the allusions, details, and the feelings of the characters, for clues and memories of what soured between them. This being a Pitol story, those are only the first imaginative layers—as simulacra builds on simulacra, metaphor on metaphor, the result is astonishing, the kind of story one could read again and again and probably discover a new dimension each time.

This threading of fiction within fiction is common throughout the collection—it is also featured in “The Wedding Encounter” and the longest story in this volume, “Cemetery of Thrushes.” The stories importune on the reader’s attention, making extensive demands of imagination and memory; the rabbit hole goes deep. Pitol even seems to anticipate criticism at one point, having one character complain to another about a story: “It had no roots, she pontificated, everything in it was too abstract. It was impossible to locate where the action took place.” One may be able to say this about a few of the tales here, but ultimately Pitol never falls into the trap of gimmickry. His metafiction—often requiring one to pay close attention as to who is imagining what—is usually a reflection on the writer as a character, or on the human need to tell stories, and not navel-gazing or a commentary on the artificiality of writing. Nor is it just a storytelling trick meant to dazzle a reader.

The idea of storytelling takes on a different form in the eerie and gothic “Burkhara Nocturne.” The unnamed narrator, a traveler, reflects back on an encounter in Warsaw two decades ago, when he had become acquainted, against his will, with Issa, a rich Italian artist. He and his friend, Juan Manuel, convinced her to change her eastern travel itinerary to visit Samarkand, the ancient Silk Road city that housed the tomb of Tamerlane. As the narrator reflects back on that time, while he is in Bukhara—another ancient city in present day Uzbekistan—he remembers the tactics he and Juan Manuel used to convince Issa to change her travel plans: “We began to use all the tricks at our disposal when we talk about such places, a hodgepodge of clichés, facile images, fuzzy details that confuse the Caucasus with Byzantium, Baghdad with Damascus, the Near East with the Far East…” It was a game for them, taking advantage of their wanderlust and her pretension, but ultimately ending tragically. Later, he rues not convincing her to visit Burkhara (“the city of Avicenna”) instead of Samarkand. The story has much more to say than that, as it meditates on travel, alienation, and the divide between the West and the East.

A capstone to this volume, “The Dark Twin” splits into a distinct essay and a short story—well, at least at first—which then come back together and develop a sort of symbiotic relationship. It begins by quoting the Spanish writer and translator Justo Navarro, who seems to have encapsulated much of what Pitol has conveyed in the stories that make up Mephisto’s Waltz: “Being a writer,” Navarro concludes, “is to become a stranger, a foreigner: you have to start to translate yourself. Writing is a case of impersonation, forging an identity, writing is passing yourself off as someone else.” The essay portion of “The Dark Twin” focuses on Tonio Kröger by Thomas Mann, and then segues into a story taking place at the Portuguese Embassy in Prague, involving a “diplomat who was also a novelist” and the imperious wife of the ambassador. It turns round to Mann again, but this time in the mind of the novelist. If it wasn’t already clear that Pitol liked to blend his genres, “The Dark Twin” also was included in Pitol’s genre-bending memoir “The Art of Flight.”

Translating the twists and turns and folds of Sergio Pitol’s sentences must have been no easy feat, which is why George Henson deserves a medal for his work here. Henson renders Pitol’s sentences in a rich mix of formality and informality—fitting for a writer who was both a lawyer and diplomat, someone so used to exacting methods of communication. At one point, however, the translation seems to stumble; Henson translates a line into the idiom “mind-blowing”—while it seems anachronistic at first, that may be a product of Pitol’s general aristocratic and anti-idiomatic voice, than something truly implausible at the time of the story. If it feels off, that may just be because it broke this reader’s hypnosis.

“If ever there was anyone who did not shut himself away,” wrote Elena Poniatowska, another Cervantes Prize winner, “it was Sergio Pitol.” Perhaps the idea of being out in the world, and part of it all, is put best in these stories by the narrator of “Burkhara Nocturne.” There is a sort of magic to that ancient city, which has been occupied for thousands of years. “I began to feel as if I were in the very center of the planet,” he says at one point. Pitol show us that the true center of the world was not a place, but the point from where all of its stories can be grasped.

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. Twitter: @gwalklin

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. Twitter: @gwalklin

©Literal Publishing

Posted: October 9, 2018 at 11:34 pm