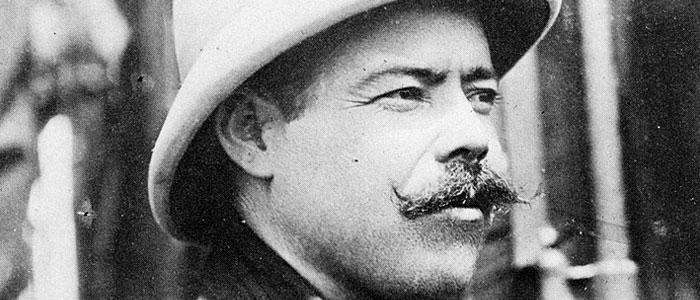

MARTÍN LUIS GUZMÁN and the paradox of random violence

Tanya Huntington

The general sentiment shared by most Mexican writers today is one of perplexed outrage. All too aware that criminal violence has taken on a terrible randomness and that simply choosing not to partake in the drug trade is no longer any guarantee of personal safety, we find ourselves appalled, moreover, by the fact that corruption has diminished (and in some parts of the country, eradicated) the capacity of the State to act as an advocate for justice, leaving us helpless to do anything other than exclaim in horror at each fresh tragedy, “¡No puede ser!”

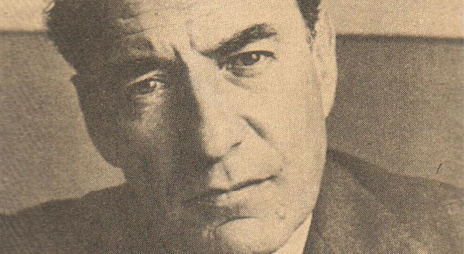

As fate would have it, while in local news this telluric panorama unfolds of implausible escape tunnels and all-too-real mass graves, I find myself proofreading a book of literary criticism I have been working on for years, soon to be published by Tusquets. The subject is Mexican author Martín Luis Guzmán (1887-1976), who participated in the Revolution of 1910 as an officer under the legendary general Pancho Villa and who penned his bestselling memoirs, The Eagle and the Serpent, during his years of exile in Spain. Under the circumstances, it was tempting for me to note some of the ways in which History—that forgetful mnemonist—has repeated itself once again.

Guzmán was pigeonholed early on as an author who portrayed “los de arriba”, or men of power, in contrast with Mariano Azuela, renowned for his seminal novel about revolutionaries titled “Los de abajo”, or The Underdogs. In an attempt to break away from this stubborn diptych, I chose to read The Eagle and the Serpent as an autobiography or rather, an “autofiction” in which Guzmán reveals that while men of action like Villa were able to freely take control of any situation, men of letters like Guzmán were paralyzed despite their commitment to the same ideal, namely, that the deplorable political and social circumstances of Mexico demanded radical change. A revolutionary in spirit, Guzmán turned out to be not only unwilling to get his own hands dirty, but powerless to do anything beyond trying to ensure his own survival.

Guzmán does not hesitate to admit that he shirked his responsibility as an officer when faced by the immoral excesses that accompany war: on the contrary, he reveals with admirable honesty that whenever push came to shove, he consistently acted in a cowardly fashion, hiding behind curtains, stymied by his fear of betrayal as various factions struggled for power. As Guzmán himself put it in a letter to Alfonso Reyes written in 1928, the same year The Eagle and the Serpent was first published in book form, “any impartial reader of my book will note that the occasions I paint myself as a coward outnumber those in which I pass myself off as valiant.”(1)

This open declaration of his own consistent inability to take on a role of leadership, not even as the protagonist of his own memoirs, belies the longstanding critical perception that Guzmán exaggerated the importance of his own role in the revolution.

Guzmán’s vision of this historic event and above all, his derogatory portrayal of himself as unworthy of the trust placed in him to carry out revolutionary business, dovetails nicely with the episodic structure of The Eagle and the Serpent, considered by many critics to be too fragmentary. Scenes pass by quickly as reality is upended from one moment to the next. There is no time to stop and think. This goes against grain of the intellectual, devoted to reflection beyond the here and now. The Revolution became a whirlwind into which Guzmán threw himself with the Quixotic dream of performing brave feats, battling wrongs and meting out justice, only to find himself paralyzed in the attempt. A useless figure as far as the immediate needs of a battered nation were concerned, even in the “hour of triumph” of his own cause, he is barely able to save his own skin.

This paralysis is partly due to the fact that as an intellectual, and a politically engaged one at that, Guzmán subscribed to a longstanding tradition founded by Parmenides, the philosopher who stipulated the intrinsic rationality of man. What to do, then, when reality itself becomes irrational, making it impossible to adapt the world to bookish standards? What happens when bullets impose their will over that of letters? When the sword proves itself to be, for the time being, mightier than the pen?

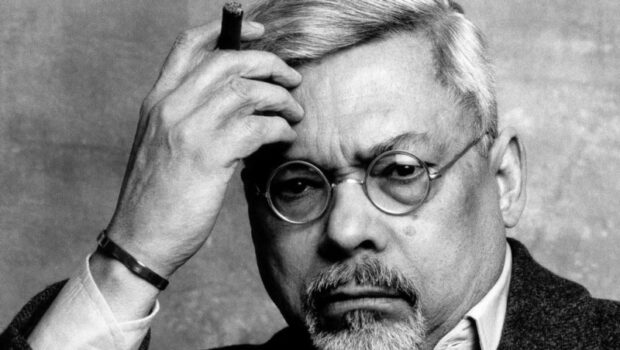

Falling back on the dichotomy of civilization vs. barbarism, I chose in my book to paraphrase the enigma expressed by Nicola Chiaromonte regarding the extreme violence of World War I, deemed necessary as the means to attain the ideal goal of socialism: a dilemma, in the end, not unlike that confronted by Guzmán in the 1910 Revolution of Mexico. How can a historic event defeat an idea, Chiaromonte asks us? In his exploration of the paradoxes of history depicted in novels like The Charterhouse of Parma, this critic wrote something that remits me to the very marrow of the narrator of The Eagle and the Serpent, suggesting that perhaps the Revolution of 1910 is also a stage upon which Guzmán strutted and fretted:

The chasm between the impulses of the soul and common ‘reality’ is just as deep in ordinary life as in a battle. For ‘real life,’ filled as it is with the deadly dregs of personal profit, utilitarian calculation […] and tinselled philistinism is the enemy of spontaneous action. Yet the world would be an insubstantial fairy tale without them. Stendhal’s double-edged irony is engendered by a vivid, vigilant and unromantic awareness of this fact. He spares neither youthful impulsiveness nor worldly wisdom. The former is doomed to destruction at its first collision with ‘real life’; the latter can only be achieved at the expense of natural feeling and free action, that is by selling one’s soul. (2)

The Revolution would act, then, as an exacerbation of our already existing human condition, in which youthful impulses will fail, wisdom will fall short, and free action will be immobilized. The inability to act in keeping with one’s own ethics during a conflict is, indeed, the equivalent to selling one’s soul. Such is the rub of finding oneself, as a humanist, immersed in a historical process—be it Revolution or drug war—in which human life is cheap. This is the perspective adopted by Guzmán, beyond any moral judgment he may have levied against military leaders or underdogs. Even taking into account the corrupt caudillos above and ignorant infantry below, caught as he was between the heaven of political power and the earth of social movements, the sentence passed down on his own shortcomings is the harshest of all. The solution Guzmán finds to this intolerable situation, that of belittling himself as comically or tragically inept, is not unlike the one described by Chiaromonte:

The wisdom of Stendhal lies elsewhere —in the ability to sustain with spirit and detachment the situation in which life places one and to play a game in which one knows that the dice are loaded, as Nietzsche put it. (3)

Herein lies the “indeterminate determinism” that is, according to Chiaromonte, the essential paradox of history. The only way out of this dead end is to exercise one’s memory of how things used to be:

Confronted with a world that appears bare and senseless, the individual is naturally led to cling to his old beliefs: to the world of yesterday. It is, however, precisely because the world is no longer what it was yesterday that he clings to the last strip of what was once credible.(4)

Which explains why Guzmán describes himself in The Eagle and the Serpent as a young man clinging to shreds of credibility from the past—from enjoying a luxurious meal in New York while people are dying out there, to futilely seeking a bureaucratic solution via telegraph while people are dying out there—exposing his own role with dark humor as none too praiseworthy, at best, and as tragically useless, at worst, given his ultimate failure to assist in the building of a modern Mexico. The outcome is a tragicomedy that transmits a sensation of the absurd, as well as a mea culpa that I find to be unique in the genre of narrative of the Mexican Revolution, through which Guzmán expresses, not unlike Hamlet in his soliloquys, his torment at having wasted through inaction an historic opportunity to change the direction his country was headed in.

Our dilemma as writers living in Mexico today is akin to that of Guzmán a century ago, minus the revolutionary ideals. Does not the same sense of the absurd pervade us? Is it not what lies behind our helpless mantra, “No puede ser”? As a profession charged with upholding reason over violence, when will we find the courage to follow Guzmán’s example and instead of considering ourselves survivors, at best, or victims, at worst, recognize our own failure in the mirror of our failed surroundings?

Notes

1 Guzmán, Martín Luis y Alfonso Reyes. Medias palabras: Correspondencia 1913-1959. Fernando Curiel (ed.). México, d.f.: unam, 1991. p. 130.

2 Nicola Chiaromonte, The Paradox of History: Stendhal, Tolstoy, Pasternak, and Others. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985. P. 17.

3 Idem, p. 22.

4 Idem, p. 88.

Tanya Huntington is the author of Return and Managing Editor of Literal. Her Twitter is @Tanya Huntington

Tanya Huntington is the author of Return and Managing Editor of Literal. Her Twitter is @Tanya Huntington

Posted: July 29, 2015 at 9:50 pm