Invention of Love

La invención del amor

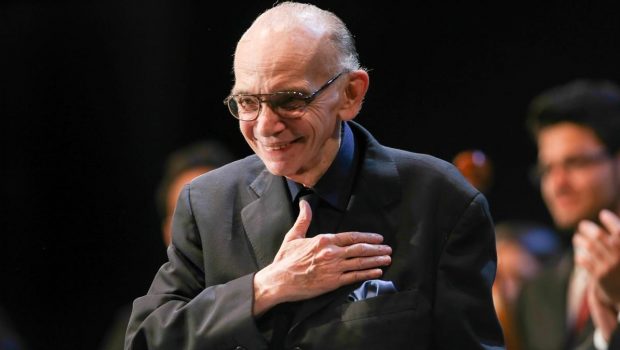

Ilan Stavans

Traducción al español de Anahí Ramírez Alfaro

Ilan Stavans is the Lewis-Sebring Professor of Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College. He is also Professor of Poetry at Columbia University. His books include the best-selling The Hispanic Condition(1995) and On Borrowed Words: A Memoir of Language(2001). He is also the editor of The Oxford Book of Jewish Stories (1998), The Poetry of Pablo Neruda(2003) and the 3-volume set of Isaac Bashevis Singer: Collected Stories (2004). Random House published The Schocken Book of Modern Sephardic Literature (2005), which he edited. His groundbreaking 4-volumeEncyclopedia Latina (Grolier/Scholastic), the first reference book to comprehensively address every aspect of Hispanic life in the United States, has been released recently. Dictionary Days: A Defining Passion(Graywolf), an autobiographical meditation on words and multilingual lexicons, has just appeared. And in November, Penguin Classics will bring out his anthology Rubén Darío: Selected Poetry and Prose.

WHO INVENTED LOVE? Animals don’t know a thing about it: many mate and separate. Since language— verbal, that is—is a unique human quality, no other animal expresses affection and becomes neurotic about it.

Or do they? In my childhood, I had a dog, a Cocker-Spaniel named Cookie—in Spanish, Cuki. She enjoyed sitting on my brother’s bed as well as mine for long hours, looking out the window at the passers-by, airplanes, and the sunset. She particularly enjoyed rainy afternoons, when a cloud of nostalgia descended on her. She would grow taciturn. Her gesture was contemplative, almost philosophical. What went on in Cuki’s mind in such moments is impossible for me to know. She certainly was a love starved pet.

In the neighborhood Cuki was known as a loner, enjoying the company of people but not of other dogs.

She lived with us for more than a decade. When my siblings and I left home, Cuki also decided to change her life: one day after breakfast, she walked out the door and disappeared.

For weeks we looked for her in vain.

Approximately a year later, my parents moved to an apartment several miles away. One day they happened to drive by the old neighborhood when they spotted Cuki in a nearby park. They told me she was with a bunch of rowdy street dogs. My parents whistled. They called her name repeatedly. Cuki finally turned around. For a minute or two she looked at them with the same concentration she had when sitting on my bed. Then, in a pose of indifference, she looked at her canine friends.

It took her less than a second to confirm the choice she had already made: Cuki rejoined her bunch.

She was never seen again.

Her love was significant, no doubt. But human love is different. Is it passion that makes a difference?

Passion is defined by the OED in a bizarre, almost mysterious fashion: “An eager outreaching of the mind… a vehement predilection.” Of the mind, I say? Wasn’t passion intimately rooted in the heart? And what does it mean to allow the mind to outreach, and to do so eagerly?

But back to love: The Acadians, Caldeans, Phoenicians, Sumerians, Babylonians, Egyptians, Normans, Toltecs, Vikings, and Quechuas didn’t have a word for it, and hence didn’t know a thing about it.

But we do… isn’t that what matters? For love is a modern invention.

The word itself—amore in Italian, amour in French, amorin Spanish, liebe in German, love in English— remind me of the definition Herbie Hancock gave for jazz: “It is something very hard to define but very easy to recognize.” Go to your local drugstore and admire the greeting-card section: Hallmark Cards has made it its duty to define love a thousand different corny ways. Or pay attention— if you dare!—to Hollywood movies: from Clark Gable’s “Frankly my dear, I don’t give a damn!” to Ali McGraw’s “Love means not ever having to say you’re sorry,” the possibilities are —for better or worse—infinite.

Love is abrasive, rowdy, obstinate, and indomitable. Also, love is orderly, flexible, civilized. It is, in short, the sum of all contradictions and its negations as well. Can a lexicon encompass, in a single definition, such opposing thoughts? Can it say what it means and not simplify it at the same time?

Francesco Petrarca, in his Life of Solitude in the fourteenth century, might have been among the first to codify it and the correspondents Abelard and Heloise the first to experience it as ethos. But within Western civilization (whatever the concept means, if it means anything at all), each culture defines love differently. To prove the point, I looked it up in a handful of translingual dictionaries, not in too many in order to keep the scientific experiment within approachable boundaries.

First, of course, is my OED. It takes the Oxford dons five pages and twelve columns to define it. “That disposition or state of feeling with regard to a person which (arising from recognition of attractive qualities, from instincts of natural relationship, or from sympathy) manifests itself in solicitude for the welfare of the object, and usually also in delight in his presence and desire for his approval.” No soon did I finish reading the definition that I remembered Dr. Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language. He included in it the word deosculation to describe “the act of kissing.” Only the lovable but love-conflicted British master would come up with such unromantic expression! Happily, oblivion has swept the term away. Otherwise, imagine a love scene in which Steve tells Arielle: “Let me deosculate you, for my heart burns in desire…”

The Trèsor de la langue française is equally fertile in its definition, if also more ardent. Amour, it states, is the “attirance, affective ou physique, qu’en raison d’une certaine affinité, un être éprouve pour un autre être, auquel il est uni ou qu’il cherche á s’unir par un lien généralement étroit.” A loose translation: Draw, either physical or affective, that based on certain affinity, can be experienced toward another being, with whom one seeks to be united in a generally internal link. The French, as usual, bring in mystery to the art of love. There is an element of uncertainty, of plenitude in this definition. Then the erudition of the Trèsor refers the reader to a 1937 novel by Jacques Chardonne, quoting its syrupy line “L’Amour, c’est beaucoup plus que l’amour.” No, love is sometimes more than just love, but also sometimes less.

I then went to María Moliner’s Diccionario del uso del español. In its second edition, amor is described as “sentimiento experimentado por una persona hacia otra, que se manifiesta en desear su compañía, alegrarse con lo que es bueno para ella y sufrir con lo que es malo.” An English interpretation: a feeling experienced by one person to another, which manifests itself in the desire for company, in the happiness for what is good to that person and suffering for what is bad. Yes, the essence remains the same but the formulation is far less frigid that theOED, more warmhearted and—excuse the cliché—quixotic. The happiness for what is good and the suffering for what is bad? Ah, this is sheer melodrama.

Salvatore Battaglia’s Grande dizionario della lingua italianaincludes pages and more pages in Italian on the word amore. The definition states: “Affetto intenso che tende al possesso del suo oggetto e all’unione con esso, e spinge a preservarne l’essere e procurarne il bene.” An attempt at translation: intense affection one possesses toward another object and its union with it, which requires its preservation and procures its well-being. The Italians appear to emphasize affection. They don’t describe the entities experimenting love as human but simply as objects. Unlike Moliner, they don’t talk about adversity: suffering? Bad fate? No, love, in plain words, is the need for possession.

The Deutsches Wörterbuch by Brockhaus Wahrig announces this methodical definition for Liebe: “tiefempfundene Zuneigung, starke gefühlsmässige Bundung an einen anderen Menschen, verbunden mit der Bereitschaft, zu helfen. Opfer zu bringen, für den anderen su sorgen usw.” An English version: Deeply felt attraction toward another person, measured strongly through feelings of bonding together, which includes readiness to help, to sacrifice and to worry about the other person’s security. The Germans not only have described it more mathematically but also more religiously. The connection established by the definition is more spiritual: it includes sacrifice, bonding beyond the immediate, and the agony of wanting the other person safe and nearby.

All this to say that the disparity between languages— and between cultures—is, invariably, a source of enjoyment. The attempt of foreign speakers to communicate with one another always results in humorous circumstances. Watch a Belgian engage in business with an Iranian while they communicate in English and you might witness some hairs being pulled off. Or observe a Peruvian and a Lithuanian in a classroom discuss philosophical issues in German and you’re likely to wonder if a couple of pints of Guinness wouldn’t help to accomplish the task a bit faster.

This brings back the memory of when my wife Alison gave birth to Joshua. By then I had been in the United States more than half a decade. While I was proficient in English, its nuances often eluded me. Alison was my living dictionary, allowing me to grasp elusive meanings. These meanings would come after a hilarious exchange.

One day, for instance, I heard the baby cry.

“He’s angry,” I said. “He needs to be fed…”

“Angry?” Alison answered. “Why would Josh be angry? He simply needs to be fed.”

“Precisely… Since he’s angry, he needs to eat.”

“Did you do something to him, Ilan?”

“Me?”

“So why would he be angry?”

“Oh, please…

“Do you mean upset?” she replied as she proceeded to give Josh a bottle.

“It’s all the same.”

“No, it isn’t” Alison added.

“What’s the difference?”

“Ilan, don’t you know the difference between angry and upset?”

“I don’t. Aren’t they synonymous?”

Alison started laughing. She quickly sent me to the dictionary, where I discovered that angry means “Passively affected by trouble,” whereas upset is defined as, among other things, “A physical or (more commonly) mental disturbance or derangement.” In other words, in one the action comes from the outside and in the other it is the product of internal change.

Why didn’t I know to distinguish between these terms? Easy: in Spanish the two are one and the same. I’ve seen Spanish/English- English/Spanish dictionaries differentiate them by establishing the former as enfadado and the latter as trastornado. But speakers—in Mexico, at least—use one instead of the other and vice versa. How could I have known that among Anglo-Protestants one needs to reckon with so many shades of a baby’s emotions?

Needless to say, the issue is far more sophisticated when it comes to adult love. The traffic of affection between two individuals is challenging enough in any language. It can only become more taxing when the lovers don’t speak the same tongue—and have no interpreter. Cervantes states in “The Dogs’ Colloquy,” part of his Exemplary Novels, that “it is as easy to say something stupid in Latin as it is in the vernacular.” But it isn’t a matter of recognizing that every language allows ample room for foolishness… and love, too. Love and foolishness are universal. Rather, the question is: Is love in one place the same as love in another?

Oftentimes, the best way to find a definition in a dictionary is to simply look up the wrong word. Years ago I read the best definition for love. I found it in a Hallmark card: “Love is a maelstrom.” I looked up maelstrom in the OED: “A famous whirlpool in the Arctic Ocean on the west coast of Norway, formerly supposed to suck in and destroy all vessels within a long radius.”

¿QUIÉN INVENTÓ EL AMOR? Los animales no tienen ni la más mínima idea de lo que es: muchos se aparean y se separan. Dado que el lenguaje —el oral, es decir— es una cualidad única de los seres humanos, ningún otro animal expresa cariño y se vuelve neurótico por haberlo expresado.

¿O les pasa también a ellos? En mi niñez tenía una perra, una cocker spaniel que se llamaba Cookie —la Cuki en español—. Le encantaba sentarse en la cama de mi hermano o en la mía por largas horas; miraba por la ventana a la gente en la calle, los aviones, el atardecer. Disfrutaba especialmente de las tardes lluviosas, cuando una nube de nostalgia descendía sobre ella. Se ponía taciturna. Su talante era contemplativo, casi filosófico. Me es imposible saber en qué estaba pensando Cuki en esos momentos. Sin duda era una mascota ávida de amor.

En el vecindario Cuki tenía la reputación de ser solitaria; disfrutaba de la compañía de la gente, mas no de la de otros perros.

Vivió con nosotros por más de una década. Cuando mis hermanos y yo salimos de casa, Cuki también decidió cambiar de vida: un día salió por la puerta después del desayuno y desapareció.

Durante semanas la buscamos en vano.

Aproximadamente un año después mis papás se mudaron a un departamento a varios kilómetros de distancia. Un día manejaban por casualidad por la antigua colonia cuando vieron a Cuki en un parque del barrio. Me dijeron que andaba con un montón de perros callejeros malandrines. Mis papás le chiflaron. Le llamaron por su nombre varias veces. Finalmente la Cuki volteó. Los miró durante uno o dos minutos con esa misma concentración que mostraba cuando estaba sentada en mi cama. Luego, con un aire de indiferencia, miró a sus amigos caninos.

Le llevó menos de un segundo confirmar la decisión que ya había tomado: Cuki se quedó con sus cuates.

Nunca la volvimos a ver.

Su amor era importante, no cabe duda. Pero el amor humano es distinto. ¿Es la pasión lo que lo hace diferente?

En el Oxford English Dictionary (OED), el diccionario más completo de la lengua inglesa, la pasión se define de manera estrambótica, casi misteriosa: “Un lance impaciente de la mente … una predilección vehemente”. ¿De la mente, me pregunto yo? ¿No está la pasión íntimamente arraigada en el corazón? ¿Y qué significa permitir que la mente tenga un lance impaciente?

Pero regresemos al tema del amor: los acadios, caldeos, fenicios, sumerios, babilonios, egipcios, normandos, toltecas, vikingos y quechuas no tenían una palabra para definirlo y, por lo tanto, no sabían nada de él.

Pero nosotros sí… ¿no es eso lo que importa? Pues el amor es una invención moderna.

La palabra misma —amore en italiano, amour en francés, amor en español, liebe en alemán, love en inglés —me recuerda la definición que Herbie Hancock dio del jazzalguna vez: “Es algo muy difícil de definir pero muy fácil de reconocer”—. Basta ir a la farmacia más cercana para admirar la sección de tarjetas para toda ocasión: las tarjetas Hallmark se han dado a la tarea de definir el amor de mil maneras cursis. También hay que prestar atención —¡se necesita valor!— a las películas de Hollywood: desde “¡Francamente, querida, me importa un carajo!” de Clark Gable, hasta “amor significa nunca tener que pedir perdón”, de Ali McGraw. Las posibilidades son —para bien o para mal— infinitas.

El amor es abrasivo, pendenciero, obstinado, indomable. También es metódico, flexible, civilizado. En resumen, es la suma de todas las contradicciones y sus negaciones también. ¿Puede el diccionario envolver en una sola definición estos conceptos opuestos? ¿Puede decir lo que significa sin simplificarlo al mismo tiempo?

En su De vita solitaria, Francesco Petrarca pudo haber estado entre los primeros en codificar el amor en el siglo XIV, y Abelardo y Eloísa entre los primeros en experimentarlo como un ethos según vemos en sus epístolas. Pero dentro de la civilización occidental (lo que esto signifique, si es que significa algo) cada cultura define el amor de manera diferente. Para probar el punto busqué la definición en algunos diccionarios bilingües; no en muchos para mantener el experimento científico dentro de límites viables.

Primero, desde luego, recurrí a mi OED. Les lleva a los catedráticos de Oxford cinco páginas y doce columnas para definirlo. “El estado emocional que tiene que ver con una persona que (surgiendo a partir del reconocimiento de cualidades atractivas, de los instintos de una relación natural o de afinidad) se declara afanosa por el bienestar del objeto, y comúnmente fascinada también por su presencia y deseosa de su aprobación”. Tan pronto como acabé de leer la definición recordé el A Dictionary of the English Language del Dr. Samuel Johnson, el primer gran diccionario moderno de la lengua inglesa, en donde incluyó la palabra deosculation (del latín osculumque dio, también, nuestra palabra castellana “ósculo”) para describir “el acto de besar”. ¡Sólo al adorable (aunque poco conocedor del amor) genio inglés se le pudo haber ocurrido una expresión tan poco romántica! Por fortuna el olvido ha enterrado esas voces. De lo contrario tendríamos que imaginar una escena de amor en donde Steve le dice a Arielle: “Me permites que te oscule, porque mi corazón arde de deseo…”

El Trèsor de la langue française es igualmente prolífico en su definición, además de ser más candente. Amour, reza, es la “attirance, affective ou physique, qu’en raison d’une certaine affinité, un être éprouve pour un autre être, auquel il est uni ou qu’il cherche à s’unir par un lien généralement étroit”. Una libre traducción sería: “atracción, tanto física como afectiva que, basada en una cierta afinidad, puede experimentarse hacia otro ser, con el cual uno busca unirse en un lazo generalmente intrínseco”. Los franceses, como es la costumbre, introducen misterio en el arte del amor. Existe un sentido de incertidumbre, de plenitud, en esta definición. Así pues la erudición del Trèsor refiere al lector a una novela de 1937 de Jacques Chardonne y cita su frase melosa: “L’Amour, c’est beaucoup plus que l’amour”. No, el amor es algunas veces más que el amor, pero algunas otras también es menos.

Entonces busqué en el Diccionario del uso del español de María Moliner. En la segunda edición, amor está definido como “sentimiento experimentado por una persona hacia otra, que se manifiesta en desear su compañía, alegrarse con lo que es bueno para ella y sufrir con lo que es malo”. Sí. El tenor es el mismo, pero la redacción es mucho menos frígida que la del OED, es más cariñosa y —disculpen el cliché— quijotesca. ¿Felicidad por lo que es bueno y sufrimiento por lo que es malo? Ajá, eso sí que es puro melodrama.

El Grande dizionario della lingua italiana de Salvatore Battaglia incluye páginas y páginas en italiano de la palabra amore. La definición dice: “affetto intenso che tende al possesso del suo oggetto e all’unione con esso, e spinge a preservarne l’essere e procurarne il bene”. Una traducción tentativa sería: el cariño intenso que uno posee hacia otro objeto y su unión con éste, que requiere su conservación y procura su bienestar. Parece que los italianos enfatizan el cariño. Ellos no describen las entidades que experimentan el amor como humanas, sino simplemente como objetos. A diferencia de Moliner, no hablan de la adversidad: ¿sufrimiento?, ¿mal sino? No, el amor es, en pocas palabras, la necesidad de poseer.

El Deutsches Wörterbuch de Brockhaus Wahrig advierte esta definición metódica de liebe: “tiefempfundene Zuneigung, starke gefühlsmässige Bundung an einen anderen Menschen, verbunden mit der Bereitschaft, zu helfen. Opfer zu bringen, für den anderen su sorgen usw”. Una versión en español: atracción muy intensa hacia otra persona que se mide estrictamente por sentimientos de unión y que incluye una disposición para ayudar, sacrificar y preocuparse por la seguridad de la otra persona. Los alemanes no solamente lo han descrito más matemáticamente, sino también con más religiosidad. La conexión establecida por la definición es más espiritual: incluye sacrificio, unión más allá de lo inmediato y la agonía de querer que la otra persona esté segura y a salvo.

Todo esto para decir que la disparidad entre idiomas —y entre culturas— es invariablemente una fuente de goce. El intento que hacen los hablantes de lenguas distintas por comunicarse siempre culmina en situaciones graciosas. Basta observar a un belga haciendo negocios, en inglés, con un iraní y seguro que los veremos metidos en camisas de once varas. Lo mismo con un peruano y un lituano en el aula tratando temas filosóficos en alemán para los cuales un par de tarros de Guinness seguro ayudarían a alcanzar el objetivo un poco más rápido.

Esto me recuerda cuando Alison, mi esposa, dio a luz a nuestro hijo Joshua. En ese momento yo ya llevaba en los Estados Unidos más de un lustro. Si bien ya podía expresarme bien en inglés, sus matices se me escapaban con frecuencia. Alison era mi diccionario viviente, lo cual me permitía comprender significados efímeros. La epifanía invariablemente llegaba después de un intercambio gracioso.

Un día, por ejemplo, oí llorar al bebé.

—Está angry —dije—. Hay que darle de comer.

—¿Enojado? —respondió Alison—. ¿Por qué va a estar enojado Josh? Simplemente hay que darle de comer.

—Exactamente… está angry porque necesita comer.

—Ilan, ¿qué le hiciste?

—¿Yo?

—¿Entonces por qué va a estar enojado?

—Ay, por favor…

—¿Quieres decir upset? —me dijo mientras se acercaba a darle la mamila.

—Es lo mismo.

—No, no es lo mismo —respondió Alison.

—¿Cuál es la diferencia?

—Ilan, ¿no sabes la diferencia entre estar angry y estarupset?

—No, no la sé. ¿No son sinónimos?

Alison comenzó a reírse. Rápidamente me mandó al diccionario donde descubrí que angry significa “levemente afectado por un problema”, mientras queupset se define, entre otras posibilidades, como “una alteración física o (más comúnmente) mental”. En otras palabras, en una la acción proviene del exterior y en la otra es el producto de un cambio interno.

¿Por qué no supe distinguir estos dos términos? Es fácil: en español los dos son uno. He consultado diccionarios español/inglés, inglés/español que los diferencian reconociendo el primero como enfadado y el segundo como trastornado. Sin embargo los que hablamos español —en México, al menos— usamos el uno o el otro y da igual. ¿Cómo iba yo a saber que entre los angloprotestantes uno tiene que tomar en cuenta tantos matices en las emociones de un bebé?

Sobra decir que el asunto se vuelve mucho más sofisticado cuando se trata del amor entre adultos. El intercambio de cariño entre dos individuos resulta todo un desafío en cualquier idioma. Sólo puede convertirse más oneroso cuando los amantes no hablan la misma lengua —y no tienen un intérprete—. Cervantes dice en pocas palabras en el “Coloquio de los perros”, parte de sus Novelas ejemplares, que “es igual de fácil decir algo estúpido en latín que en lengua vernácula”. Pero no se trata de aceptar que en todos los idiomas hay gran cabida para los disparates… y en el amor también. El amor y los disparates son universales. La pregunta sería más bien: ¿el concepto del amor es el mismo en un lugar que en otro?

A menudo la mejor manera de encontrar una definición en un diccionario es simplemente buscar una palabra incorrecta. Hace años leí la mejor definición de amor. La encontré en una tarjeta Hallmark en inglés: “El amor es un mäelstrom”. Busqué la palabra mäelstrom en el OED: “Conocido vorágine en el Océano Ártico en la costa occidental de Noruega de tal magnitud y alcance que en otros tiempos se pensaba que el impetuoso remolino succionaba y destruía todas las embarcaciones en su paso”.

![Entre Pink Floyd y el INAPAM [1]](https://literalmagazine.com/assets/patti-620x350.png)

Well I definitely enjoyed reading this article. Keep up with the good work!