AN UNFLINCHING LOYALTY TO MEMORY

BRAULIO MUÑOZ

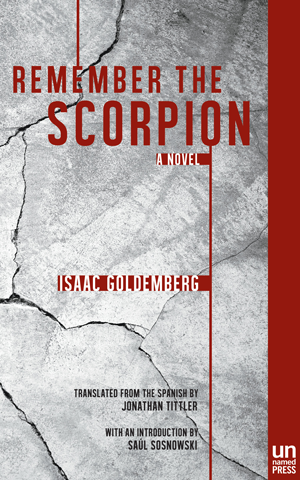

Isaac Goldemberg, Remember the Scorpion (translated by Jonathan Tittler, with an introduction by Saúl Sosnowski). Los Angeles: Unnamed Press, 2015.

A good novel, as Isaac Goldemberg has said on more than one occasion, must not only tell a good story;it must also say something meaningful about the human condition. Since I find Remember the Scorpion to be a very good novel, what does it say about the human condition? A good question with which to approach a tautly written novela negra, it would seem. And since the story of Remember the Scorpion is set against the background of mid-twentieth century Peruvian cultural tradition, perhaps we should start there in order to find some answers.

The first thing to note is that Goldemberg sets the story against a sharply drawn condition of mestizaje, the process of cultural and biological miscegenation. This cultural process, even in its most intensive form, is not peculiar to Peru, of course: it occurs everywhere and at all times, and it always entails perils as well as opportunities. In the Americas over the last five centuries, we can identify in the human condition at least two distinct cultural or ideological stances regarding this process. Up until very recently in the United States, the process was celebrated as ushering in a “melting pot” where subaltern cultures and races (with gradient forms of acceptance) were absorbed into the hegemonic white Anglo-Saxon Protestant cultural traditions. On the other hand, since at least the beginning of the last century, intellectuals from Mexico to Peru have come to see the mestizo as a “new man”; that is, a being emergent from cultural and biological miscegenation. To be sure, both of these stances were upheld against a fickle reality: most mestizos seem interested in fitting into the larger hegemonic culture but, at the same time, they seem to wish to keep their cultural differences alive.

Remember the Scorpion, written in the tradition of a novela negra, weaves a story that interrogates a very specific slice of mid-twentieth century Peru: the mestizo culture of Lima as it was in June of 1970, two days after an earthquake hit the country and more than 70 thousand people died. In brief and deft strokes, Goldemberg paints detective Simón Weiss’s Lima for us. What we find as we follow the detective’s gaze is a sprawling city where pockets of diverse, well-delineated cultural traditions co-exist. In each one of these cultural enclaves––where markers of class, cultural, and racial distinction are heightened––we find sediments of despondency, memories, traumas, and dreams. As we follow the gumshoe’s trajectory, we visit upper-, middle-, and lower-class neighborhoods peppered with recognizable cultural centers as well as whorehouses, betting halls, and opium parlors. In the process we realize that the capital of Peru is made up mostly of recent migrants: native Peruvians who have come down from the highlands, creoles who have retreated from downtown, blacks, Chinese, Jews, Japanese, Germans, and other ethnic groups.

In this presentation of Lima, we are offered the truth that individuals cling tightly to their cultural tradi tions even as they wish desperately to belong. But there is something else: Goldemberg also offers that, just when individuals are feeling at home in their newfound land, the past they carry within rises to upset all their best laid plans. At the beginning of the novel, there is a murder-by-hanging of an elderly Jewish man and Simón Weiss––a Jew who arrived in Peru when he was ten years old––is given the job of solving the crime. And thus, the world he has managed to fashion for himself in Lima is upended.

tions even as they wish desperately to belong. But there is something else: Goldemberg also offers that, just when individuals are feeling at home in their newfound land, the past they carry within rises to upset all their best laid plans. At the beginning of the novel, there is a murder-by-hanging of an elderly Jewish man and Simón Weiss––a Jew who arrived in Peru when he was ten years old––is given the job of solving the crime. And thus, the world he has managed to fashion for himself in Lima is upended.

As he walks through a city in ruins trying to find answers, in a different cultural enclave a Japanese immigrant is also murdered. He is to solve that homicide as well and, because of the cultural differences in play, he is assigned a junior partner: Lieutenant Kato Kanashiro. As the two detectives dig into the case, it comes to light that, in fact, the murders are related, though not directly. They are both final acts in courses of events set in motion during the second World War. The past, Goldemberg suggests, does weigh heavily on the living, and deeds committed against a people are seldom forgotten or forgiven.

Goldemberg offers another side of the human condition to be found in mid-century Peru. As the country lies in ruins after the devastating earthquake, the national soccer team wins in the early rounds of the 1970 World Cup, held in Mexico City. The battered spirits of Peruvians are lifted by a ragtag team of soccer players who give it all in the pitch. Their cries of “¡Gooool!” provide much-needed respite from bitter tragedy. Goldemberg shows that human resilience flares precisely in our darkest hours.

And here is where the two insights offered by Remember the Scorpion concerning the human condition during mid-twentieth century Peru come together: this is no ordinary soccer team. This is a team made up of mestizo players from the different parts of Peru; a team where blacks, native Peruvians, whites and others from different ethnic traditions came together behind one jersey. This is a team from a country that remembers that, in Berlin, during the Olympic Games of 1936, its players won the title match against Germany only to be denied victory by the Nazis, who could not abide mestizos winning against their pure race.

Yet another aspect of the human condition seems clear at this point: after Kanashiro and Weiss have discovered the murderers and have each executed the roles assigned them by their own pasts, they realize that, despite all the confusion of cross-cutting obligations, they have remained true to their individual natures and followed their own designs, given to them under the sign of Scorpio: loyalty. Both are loyal to each other in the hard-boiled process of crime solving but equally importantly, they are both loyal to the inherited memory of their own people. Through Kanashiro and Weiss, battered communities exact a revenge dreamed of years before.

Memories do not exist in cities or nations, however; they exist only in individual souls. Seldom, if ever, do individuals live only in or for the past. At least this is true for Simón Weiss and Kato Kanashiro. At the end of the novel, Kanashiro goes back to his mestizo sweetheart, even though her family still calls him a Jap. The man is determined to find his place in the mestizo world around him. As for Weiss, when he meets Olga, the daughter of a fellow prisoner in the concentration camp of Sachsenhausen, he falls in love with her as if he were falling in love with himself. He abandons Margarita, his mestizo live-in partner of many years, for Olga. In the end, however, his gateway toward childhood is impassable. Olga disappears. In the tradition of the novela negra, Weiss ends up back in the opium palace to dream of better worlds.

Braulio Muñoz (1946) is a social theorist, writer, critic, and Centennial Professor of Sociology at Swarthmore College. El Misha (Estruendomudo, 2014) is his most recent novel.

Braulio Muñoz (1946) is a social theorist, writer, critic, and Centennial Professor of Sociology at Swarthmore College. El Misha (Estruendomudo, 2014) is his most recent novel.

Posted: October 8, 2015 at 8:26 pm