Language is the Motor that Moves Everyone A Conversation with Wendolyn Lozano

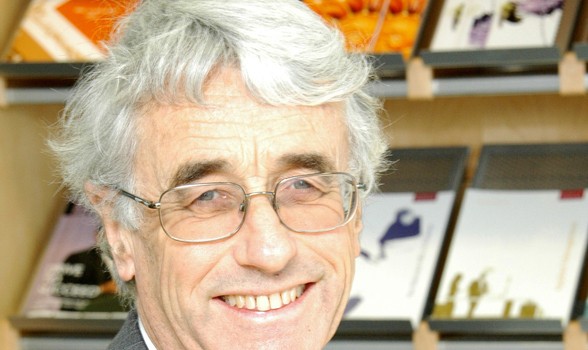

Margaret Atwood

Margaret Atwood, (Ottawa, 1939) is one of the world’s preeminent writers –winner of the Booker Prize, the Scotiabank Giller Prize, and the Governor General’s Literary Award, among many other honours. She is the bestselling author of more than thirty-five books of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction, including The Handmaid’s Tale, Alias Grace, The Blind Assassin, and Oryx and Crake. She is an International Vice President of PEN, which assists writers around the world in the peaceful expression of their ideas. Most recently, she is the 2008 recipient of the prestigious Prince of Asturias Award for Letters.

* * *

Wendolyn Lozano Tovar: Hölderlin once said that men inhabit the world in a poetic manner. In that regards, language is the essence of humans. It is language that allows us to name and acknowledged the world. You have been recognized with The Prince of Asturias Award in Spain, not only for your literary work but also for your social and environmental involvement. Is language the link, the motor that moves you to integrate these two activities?

Margaret Atwood: Language is the motor that moves everyone. It’s one of the most human things about us. It’s not that other beings don’t have language or, say, modes of communication. They do, but they don’t have the past tense or the future perfect tense. And it’s not that they don’t have memory. They do, but they cannot post a periodical question as far as we know. Rover the dog is unlikely to say to himself “where was I before I was born?” or “where do dogs come from?” Rover was in the world before there were dogs whereas humans, because we have a grammar that includes these tenses, we can indulge in infinite regression and infinite progression. We can also say “what would happen to me when I die?” Rover the dog can’t say that. That’s as far as we know. He can’t say “I remember that postman kicked me so now I’ll bite his bike”. He can’t say “it’s five o’clock and my beloved friend –who is a human being— should return at about this time, therefore I’ll wag my tail and walk out the window because I remember that should be happening”. He can’t generalize about dogs; about time before dogs or time after dogs; about time before himself or time after himself. Human beings do that however; that and singing are two of the most human things that we have. The other beings that sing the way we do are certain birds. So there you have that the kind of languages that we have created are the mark of our humanity and therefore people that say that writing and poetry are frills, are wrong, because they are much more essential to be human than accountancy, which is a recent thing whereas language is very ancient and much more essential to be human than some of the modern things that you think are very clever. It’s more human to have a human language and grammar than it is to have a computer. Language by its nature is of course metaphoric so poets are the guardians of the metaphor. They are the first to realize when language is being used to manipulate and when it conceals negative metaphors.

WLT: You were once asked in an interview “if you could steal any object, what would it be?” You said back then you’d steal the hummingbird vessel of the Mixtec culture from the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City and you wrote a poem about this miniature cup which makes you wonder “Who made it? / Who was it made for? / Who poured what into it? / With what pleasure?” Can you tell us what drives you to incorporate primitive and ritual imagery in your work?

MA: Because this is what the hummingbird cup must have been for. We don’t actually know but it must have been for something like that because you couldn’t drink out of it very well. So, what was it? We don’t know but it’s one of those mysterious objects and wherever there is mystery, there is room for poetry. It’s only when we know everything that we can’t write poems. The National Museum is beautiful. There are a lot of miniature things in those cultures. In the Yucatan peninsula, if you go underground into a tunnel which the Mayans walled up, there’s a shrine to the water god who is sitting in the water with little miniature things; tiny rolling boards and tiny little tortillas made of clay. It reminded me of these little silver milagritos that people pin to the Virgin Mary’s clothing. Maybe those miniature symbols are offerings to the gods. We don’t know. It’s a mystery.

WLT: In The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard says “If one were to give an account of all the doors one has closed and opened, of all the doors one would like to re-open, one would have to tell the story of one’s entire life”. You have done so in your poem The Door.

MA: A little bit, yes.

WLT: What can you tell us about this dark space you are confiding yourself to?

MA: Well, the person in the poem isn’t me. It’s just everybody. The dark space is death, obviously, but what’s down there we don’t know. No one has ever come back to tell us.

WLT: In your poem The poet has come back you say it’s time to unlock the cellar door. Are you letting the gothic spirits out?

MA: You know the answers to all these questions already because you are a poet. The cellar is where the unconscious is stored. Poetry is connected to the unconscious part of the mind so opening the cellar door also is opening the door to poetry. It’s not that there are necessarily bad things in the cellar but there are forgotten things.

WLT: You said curiosity is what motivated you to write your latest non-fiction book Payback: Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth when the world is experiencing one of the most disquieting economic troubles and the prospect of irreparable ecologic damage. How does your scientific background nurture your imagination and encourage your curiosity?

MA: Payback has much more to do with the examination of metaphors rather than the examination of science. Science gives you certain examples of things that you can use but the whole language of finance is composed to conceal metaphors. Even these charts of the stock market going up and down; it’s completely a metaphor. They don’t really go up and down; we’ve invented that to describe how we feel about it. We could do it in the reverse direction. We could do it vertically. There’s also some ways that we could draw that but we draw it going up because the up direction makes us feel happy. The down direction would make us feel bad, so up like a balloon, down like a balloon. The up-down motion is our way of expressing our feelings about these numbers which are an invention that we do. Money is an entire human invention. The whole financial structure is something we invented originally to make trade easier so you didn’t actually have to take your cow to where the horse was and trade it. You could put that third thing in between which represented the cow and the horse and then you could exchange those markers and then you got whatever it was. But like other things we invent, it got out of control. We are always inventing things that get out of control. So I was interested much more in the story of debt, the language of debt and, underneath that, in the fundamental human characteristics that allowed us to have debt and credit in the first place. They are called trust and reciprocity; trust and distrust. Credit means that somebody believes in you enough to give you the credit because it’s the same route as to believe; it’s credo. Giving you a credit card means that I believe in you. I believe that you are going to pay and when there is a credit crisis it’s because people have stopped believing. So the air comes out of the balloon because people are not believing that it’s still up there. I was interested in the trading nature of debt and credit because it is an extension of trading. Social animals trade and recently there was an article on chimpanzees. You know the expression “I’ll scratch your back if you scratch mine?” They really do trade backscratches. They can’t actually scratch their own backs, not easily enough, so they keep track of whose backs they scratch and who owes them a scratch in return. If that scratch isn’t repaid they are much less likely to put out another scratch. Little children learn early on start saying “that’s not fair” long before they start saying “how much does that cost.” They get the fairness and unfairness much earlier than they understand money. It’s an early retaliation: if I hit Billy, he is likely to hit me back. This is foundational to the whole system of borrowing and lending that we call financial institutions. Now, borrowing and lending are, in the good aspect, a social rule because if you lend money to somebody you create a social bond as well as a bond of another kind, one that says “you have to pay me back”. We have an agreement. Debt and credit are out of balance until that loan is paid off; then the scales are even again. We have a great interest as a species in balancing scales. What’s fair? Who owes me? Where do I exist in the social scale? What does that get me? We are doing these calculations all the time. If you say good morning to somebody and they don’t say good morning back you feel really quite hurt, angry or even puzzled because things are not even. In ordinary human interchange one good morning deserves another good morning. There’s an interaction going on all the time.

WLT: In your novel Surfacing you wrote that “everything we could do to the animals we could do to each other”.

MA: And we have… even worse.

WLT: What does it mean to be human in the environmental context?

MA: I can bring it down to a very simple fact: if there were to be no other life on earth, there would not be human beings, either. Everything we eat, drink and breathe comes from the planet so if you kill all the life –and I mean all other life— there would be no food, just to begin with. If bees go extinct we are going to have a hard time because they pollinate our food and if you get rid of the bees and they all die, everything that is pollinated with them is in trouble. The trees produce our oxygen. What would happen if there aren’t any trees? We would choke to death. So it’s really very simple: we need it, it doesn’t need us.

WLT: In your 2008 Massey Lecture you mentioned that countries from the north –especially in the European and American continents— are enriching themselves to the detriment of the countries from the south such as Africa and Latin America. Can you elaborate on this?

MA: Everybody knows that. How do they manage to do it? Well, there’s this thing called money, which we invented and it’s very interesting how a completely imaginary thing can have such real consequences. Money only has value if everybody agrees that it does so it’s a collective agreement that certain things have value. If you are asking me how does the international financial system work not even they know that anymore. The system has become so complex and so dependable to computers and algorithms that nobody quite knows what’s really happening in the financial world, in this huge brain that we’ve made which is linked electronically and where transactions can happen in less than a second. Nobody quite knows how it’s working anymore: it’s taken on a life of its own but what it usually means is that an entity has lots of money and it’s able to buy elsewhere for cheaper prices. Political corruption plays its part, too. If Country A lends Country B a lot of money and that money gets into the hands of corrupt leaders and they put it into a Swiss bank account, it doesn’t really benefit the people who will have to pay for it anyways through their taxes and that’s called…. bad. Bad behavior but it has happened a number of times in the twentieth century. Money doesn’t get to the people; it gets to the dictator who keeps it.

WLT: You have been to Latin America various times. What is it about the Latin spirit that you like?

MA: It’s different in each country. I was just in Argentina which is a very different place from Mexico and Mexico is very different from Costa Rica or Ecuador. I’ve been to Brasil and it’s very different again from Argentina. Cuba is very different from all of the other places. It’s a whole bunch of different countries each of which has its own reality. Most of them speak Spanish, some of them speak Portuguese. Each has its own history and geography and the geographies and histories are very different. What they do share, to a certain extent, is literary history as well as religious history. There are books that are well known to people who read in each country, like Don Quijote for instance, but each of those countries will have a different relationship with that particular book. One of them has Eva Peron preserved in wax while others don’t. Some of them have Aztec temples, others don’t. Some of them bring European arrivals and very complex urban civilization, others didn’t. So it’s an extremely varied and complex world that people standing far away from it might think it is simple because they can call it Latin America but that thing doesn’t exist as a homogeneous being.

Posted: April 16, 2012 at 6:54 pm