Colin Crouch. The Day After Tomorrow

Colin Crouch. El día después de mañana

Florian Christof

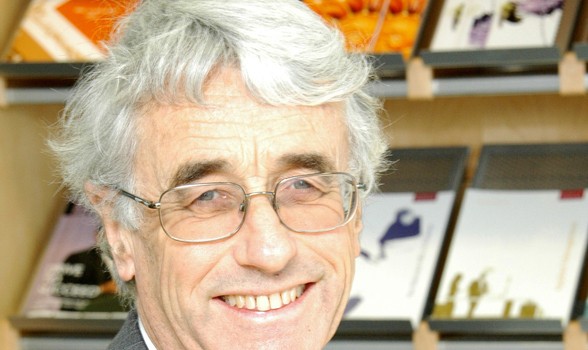

Colin Crouch is Professor Emeritus of the Warwick Business School (Warwick University, United Kingdom). He is also a member of the British Academy and the Max Planck Institute for Social Research of Cologne. His best-known works include Post-democracy: Themes for the 21st Century Series (2004), a widely read volume regarding the capacity of elites to coerce governments, focusing especially on the power of mass media in the 21st century. Likewise, the German edition of The Strange Non-Death of Neoliberalism (2011) was considered the best book on politics in 2011 by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation. Crouch was interviewed by Florian Christof, editor of the Supertaalk site, during the author’s book tour through Germany.

* * *

Florian Christof: If you had to give a very brief definition of what the term “post-democracy” means, let’s say in a few sentences, what would it be?

Colin Crouch: Post-democracy would be like post-industrialism. Post-industrial society–we have all the products of industry. Industrial activity continues. But the energy, the dynamism of the economy has gone somewhere else. I use post-democracy with the same idea. All the institutions of democracy remain–we use them. It’s just that the energy of the political system and the innovative capacity have moved on to other spheres.

FC: Since your analyses and the critique you came up with focus mostly on the Anglo-Saxon system of democracy, why is it that the book got such a great response in Europe, where many countries have multi-party-systems? Unlike the US, for example.

CC: It was based originally on the British, American and Italian experience. The book was published first in Italy, in fact, and had big resonance with the public there. But I could understand that, because of the Berlusconi phenomenon. I have been surprised at the resonance the book had in Germany and Austria also. I am slightly puzzled by this. I think it could simply be that my thought processes are more accessible to German people than to English-speaking people.

FC: Your book said the crisis of classic democracy started in the 1980s, or something along those lines. It was at the same time the neoliberal doctrine became very popular in the US and the UK; when Reagan and Thatcher started massive off-shoring and privatization of the public sector. David Harvey mentioned this in a brief video, saying that in central Europe, people like to call it an Anglo-Saxon disease. Does the decline in the functionality of democracy have anything to do with the neoliberal doctrine? Did it really come to the privatization of politics? What are the coincidences?

CC: Yes, they are very closely related. And in the new book, I have just written about why neoliberalism survived the financial crisis, which should have made it very vulnerable. I have tried to make these links. It’s a very close relationship, indeed. Because the growing power of large corporations is a fundamental aspect of the shift of post-democracy. When I say the political energy of the system has gone elsewhere, it has gone to a rather secret private discourse between great global corporations and governments.

FC: Your thesis came out a few years ago. It doesn’t say much about the European Union and the Euro System, which is the current topic of the day. Can we get a brief statement on what your personal opinions are about the outlook of the EU and the stability of the Euro System?

CC: Fundamentally, the European Union is a very optimistic sign. One of the problems that democracy has is that the economy is global and democracy remains very, very national. The European Union is a means to getting beyond that. Unfortunately, the European project, like it is now defined, is a very neoliberal project. In particular the Monetary Union is more Anglo-Saxon then the Anglo-Saxons are. This is a design fault of the system, which Europe is suffering from.

FC: If we consider the rise of nationalism in central Europe, is common economic governance of the EU possible?

CCH: Sadly, the prospect is very poor. There are at least two things. On the one side, neoliberalism: As Fritz Scharpf, the German political scientist has argued, market making is a negative form of constructing Europe. It’s much more easy to do than positive institution building. So that’s one set of problems. The other set of problems is that national reaction to globalization is increasingly taking this xenophobic form. Now these are two very negative forces preventing the construction of a good, social Europe.

FC: What started as a protest movement against unemployment and a failing political system in Spain with the slogan “Real Democracy Now!” has now overflowed to other parts of Europe and the US, where the Occupy Wall Street Movement has garnered considerable attention from the media. Now, this seems to be the beginning of a global rise of resistance to certain situations created by governments. Do you expect this to become a solution for the post-democratic dilemma? In Austria, there’s quite a big discussion going on about traditional forms of participation (via the representative system) versus new forms of democratic participation; for example, it’s better to found a party, because this is the only possibility the representative system gives us to make a difference.

CC: We need both parties and civil society initiatives. We cannot expect parties to do this alone, unless there is a real strong feeling in the public opinion that something must be done about this financial system and about this form of capitalism that we have. We cannot expect the parties to create that by themselves. So we need to support movements and protests that articulate this concern, and try to create a strong movement of public opinion, to which the parties can then respond. I don’t see parties and bürgerinitiativen as alternatives, they are necessary to each other.

FC: Much has been written and said about the role of new forms of technology and systems of communication like social media. Richard Wilkinson has mentioned the potential of free information and the conflict over restrictions on it. Do you think they have the capability to assist and establish a more democratic society, more active citizens, in a democratic sense? Or do they probably lead to, as some skeptics say, a decline of public interest in politics?

CC: Well, they are serving very well, in assisting organizations with slim resources. I think it’s rather similar to the history of newspapers. When newspapers, mass newspapers started, the existing elites were not interested because they did not control them. There was a great diversity of ownership, and this helped all kinds of opposition opinion: liberal groups, working class groups, anti–religious groups. Eventually, the great power centers understood this and began to buy up newspapers and controlled most of them. And I expect we shall see the same with new media, but at the moment, we are living in the period where they are useful to, and are being used by, all kinds of groups.

Colin Crouch es profesor emérito de la Warwick Business School (Universidad de Warwick, Reino Unido). También es miembro de la Academia Británica y del Max Planck Institute for Social Research de Colonia. Entre sus libros más destacados se encuentra Post-democracy: Themes for the 21st Century Series (2004), volumen ampliamente difundido cuyo tema es la capacidad de coacción de las élites sobre los gobiernos, en particular del poder de los medios de comunicación en el siglo XXI. Asimismo, The Strange Non-Death of Neoliberalism (2011), cuya edición alemana fue galardonada como el mejor libro sobre política en 2011 por la Fundación Friedrich Ebert. La siguiente entrevista, realizada por Florian Christof, editor del sitio Supertaalk, se realizó durante una visita promocional del autor a Alemania.

* * *

Traducción al español de José Alfonso Toledano

Florian Christof: Si tuviera que dar una definición breve de lo que el término “posdemocracia” significa, ¿cuál sería?

Colin Crouch: La posdemocracia es como el posindustrialismo. En la sociedad posindustrial tenemos todos los productos y una actividad industrial continua. Sin embargo, la energía y el dinamismo de la economía se han ido a otro lugar. De modo que cuando utilizo el término posdemocracia es con la misma idea. Todas las instituciones de la democracia continúan siendo empleadas. No obstante, la energía del sistema político y su capacidad de innovación se han trasladado a otras esferas.

FC: Dado que el análisis y crítica de su libro Post-Democracy está particularmente enfocado al sistema democrático anglosajón, por qué el libro obtuvo tan importante respuesta en Europa, donde muchos países carecen de sistemas multipardistas como en EE.UU., por ejemplo.

CC: Originalmente, me basé en las experiencias británica, estadounidense e italiana. Y en realidad, Post-Democracy fue publicado primero en Italia y despertó un gran interés de su público. El hecho puede entenderse por el fenómeno Berlusconi de ese momento. En cambio, me ha sorprendido la resonancia del libro en Alemania y Austria. Estoy un poco desconcertado por ello. Creo que podría ser simplemente que mis procesos de pensamiento son más accesibles a los alemanes que a los angloparlantes.

FC: Cuando leí su libro me extrañó la afirmación de que la crisis de la democracia clásica se inició en la década de 1980, aproximadamente. Fue un tiempo en que la doctrina neoliberal se hizo muy popular en EE.UU. y el Reino Unido, cuando Reagan y Thatcher comenzaron la subcontratación y privatización del sector público masivas. David Harvey señala que en Europa Central a la gente le gustaba llamar a este fenómeno “la enfermedad anglosajona”. ¿Hay alguna coincidencia entre el declive de la funcionalidad democrática y la doctrina neoliberal? ¿De verdad experimentamos la privatización de la política? ¿Cuáles son las coincidencias?

CC: Sí, están relacionadas estrechamente. En un libro que acabo de escribir, The Strange Non-Death of Neo-liberalism, hablo sobre por qué el neoliberalismo ha sobrevivido a la crisis financiera cuando debió volverlo muy vulnerable. He tratado de explicar ahí estos vínculos. Por cierto, se trata de una relación muy estrecha debido a que el creciente poder de las grandes empresas es un aspecto fundamental en la transición hacia una posdemocracia. Entre tanto, la energía política del sistema se ha ido a otra parte –se ha desplazado al discurso más bien privado y secreto entre las grandes corporaciones globales y los gobiernos.

FC: Su tesis apareció hace algunos años y apenas aborda a la Unión Europea y el sistema del euro, la noticia del día. ¿Podría darnos una breve opinión acerca de las perspectivas de la UE y su estabilidad monetaria?

CC: Fundamentalmente, la Unión Europea es muy optimista. Sobre todo porque uno de los problemas que enfrenta la democracia actual es que la economía es global mientras que la democracia sigue siendo muy, muy nacional. La Unión Europea constituye un medio para ir más allá de esto. Lamentablemente, tal y como se define ahora el proyecto europeo, ha sido marcadamente neoliberal. En particular, la unión monetaria es más anglosajona que los anglosajones mismos. Se trata de una falla en el diseño del sistema que repercute en toda Europa.

FC: Si consideramos el creciente nacionalismo de Europa Central, ¿es posible un gobierno económico común en la UE?

CC: Desgraciadamente, la perspectiva es muy mala. En este sentido, hay que considerar al menos dos cosas. Por un lado, el neoliberalismo: como el politólogo alemán Fritz Scharpf ha sostenido, la creación de un mercado es una forma negativa de construcción europea. Pero es mucho más fácil en comparación con la creación de instituciones positivas. Todo eso implica un conjunto de problemas. Otro es que la reacción nacionalista ante la globalización adopta cada vez más una forma xenófoba. Se trata de fuerzas muy negativas que impiden la construcción de una Europa socialmente favorable.

FC: Lo que comenzó en España como un movimiento de protesta contra el desempleo y el sistema político endeble –bajo el lema “¡democracia real ya!”–, se ha expandido a otras partes de Europa y EE.UU., donde el Occupy Wall Street Movement ha atraído fuertemente la atención de los medios. Parece el inicio de una resistencia global creciente ante situaciones propiciadas por los gobiernos –resistencia de la que usted espera ver surgir alguna forma de superar el dilema posdemocrático. En Austria se está llevando a cabo una discusión acerca de las formas de participación tradicionales (las vías propias del sistema representativo, donde un partido nos brinda la posibilidad de lograr ciertos cambios) frente a nuevas alternativas de participación democrática.

CC: Necesitamos los partidos tanto como las iniciativas de la sociedad civil. No podemos esperar que aquellos hagan nada por sí solos, a menos que suceda una fuerte y auténtica presión por parte de la opinión pública para que hagan algo con el sistema financiero y las formas del capitalismo con las que contamos. No podemos esperar que los partidos actúen por sí mismos. Así que tenemos que apoyar a los movimientos y protestas articulados en torno de esta preocupación tratando de crear un movimiento de opinión pública fuerte ante la que dichos partidos deban responder. No veo a los partidos e “iniciativas ciudadanas” como alternativas excluyentes: son necesarios los unos y las otras.

FC: Mucho se ha escrito y dicho sobre el papel de las nuevas tecnologías y las redes sociales. Richard Wilkinson, por ejemplo, habla del potencial de la información libre y los conflictos por sus restricciones. ¿Cree usted que tienen la capacidad de ayudar a crear una sociedad más democrática –con ciudadanos más activos? ¿O es que nos conducirán a lo que algunos escépticos señalan como la disminución del interés público en la política?

CC: Bueno, están cumpliendo muy bien con su ayuda a las organizaciones con recursos muy escasos. Creo que se trata de una historia bastante similar a la de los periódicos. En los inicios de la prensa escrita masiva, las élites existentes no estaban interesadas en ella y no la controlaban. Esto propició una gran diversidad en términos de propiedad, lo que dio cauce a todo tipo de opinión disidente –liberales, de la clase trabajadora o grupos anti religiosos. Finalmente, los grandes centros de poder cayeron en la cuenta y comenzaron a comprar y controlar la mayor parte de dichos diarios. Supongo que veremos lo mismo con los nuevos medios de comunicación. Aunque, por el momento, estamos viviendo un periodo en el que son muy útiles y son el recurso básico de una diversidad enorme de grupos.