Sebastián Gordín: two of us

Fernando Castro R

“Soy medio contrabandista también; en el sentido de que hay ciertas cosas que están un poquito ocultas bajo varias capas”.

(I am also a bit of a smuggler —in the sense that there are things that are somewhat hidden under several layers.)

Sebastián Gordín

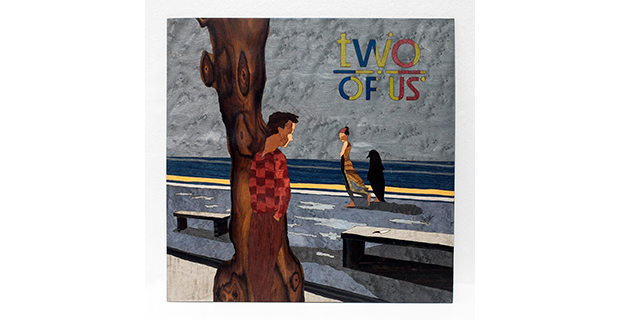

Two of us. 2023. 33×33 cm

Some album covers are more iconic than cans of Campbell soup. Who can forget The Beatles 1969 album cover Abbey Road? Or the 1967 album The Velvet Underground & Nico, with a banana design by Andy Warhol —infamously quoted by Maurizio Cattelan in his 2019 Comedian? At your own peril, try to ignore Santana’s intoxicating hymns of a generation in the 1970 album Abraxas. In fact, more than iconic, they are sonic, because if you see one of these covers you can remember music from the album and vice versa. In a convoluted sort of way, that is the idea behind Sebastián Gordín’s new exhibit Two of Us, except his works do not allude to a pre-existing album cover. Instead, he has appropriated from actual songs the titles of some of his works, whose visual content often clash with them.

Sebastián Gordín (b. 1969) is an Argentine artist well-known for his whimsical boxes, cartoonish magazine covers, and intriguing miniature maquettes of things like The Museum of Zombie Art, the Odeón movie theaters, libraries, bar scenes, etc. For Two of Us he has crafted works the size of an album cover using marquetry; i.e., inlaid work made with thin wooden laminates cut and sliced with a laser cutter. Besides drawing, Gordín performs the acts of designing, fitting and gluing that marquetry requires. Those skills separate him from many conceptual artists who either lack a craft or chose not to use it in order to focus on ideas. As a matter of fact, throughout his artistic career Gordín has shown to be endowed with many crafts. Early in his career he drew comic books, and later developed skills for constructing incongruous objects, for assembling electrical gizmos, and most notably, for building scale models. The works in two of us resurrect a comic book style of depiction with a twist of Hopper, Goya and Chris Ware.

Many of Gordín’s works bear the titles of actual songs from The Beatles, Los Gatos, Virus, etc. Take “All my loving,” Paul McCartney’s moving love song made famous by the Beatles around 1964. By contrast, Gordín’s work by the same name is a rather macabre depiction of a vulture eating the lip of a human corpse. For “All my loving” (2023), Gordín lays bare the material characteristics of the wood. An undeniable undercurrent of dark humor in Gordín’s oeuvre at times surfaces in his oeuvre. Another work that fits that noir category is “Nowhere man” —after the 1965 Beatles song by Lennon and McCartney. The original song is a critique of an “un-involved” person —ancient Greeks called them idiotes. Gordín’s work depicts a man jumping over a bridge in an otherwise bucolic landscape. In a YouTube video Gordín mentioned his childhood spent during the times of the worse political terror in Argentina as a probable source of his darkness.

“Para nadie” (2023) also alludes to a lesser known but poignantly sad Beatles’ song titled “For no one.” It is one of the strangest works in this exhibit: a person sits to write a letter to nobody. Thanks to a knot in the wood, and his reflection on the window pane we realize he is a cyclops. The title begins to make sense filtered through The Odyssey ‘s episode when the cyclops Polyphemus complains to his father Poseidon that “No One has blinded him” —falsely believing Odysseus’ name to be “No One.” If not his father, who is the cyclops writing to? To make Gordín’s work even stranger, a small action figure of Manolito, the Mafalda business-oriented character, stands to one side in the picture, as if planning his next marketing campaign.

Gordín often refers to himself as a builder. “Music from the cutting edge” (2023) is his tribute to another builder: British musician Henry Dagg. It shows a man wearing a flowery shirt playing the saw. The punctum of the work is the handwritten note from V., an angry person who explains to a Sebastián that she has scratched his vinyl Dagg record but has “mercifully” spared the rest. The work then turns from a tribute of a fellow builder, to a love affair gone sour; as if a musician had suddenly switched to the cutting edge of the saw. Moreover, the double-entendre in the title plays on the fact that the edge of the saw that a musician is supposed to play is not the one that cuts; but the blunt one is. In other words, if you so choose you can destroy the instruments of your art and even your art itself by playing the really cutting edge, but with a little less nihilism you can still play the blunt edge of the saw. The avant-garde sense of the phrase “cutting edge” still holds its meaning even if Dagg were to play “On the sunny side of the street.”

There are other works in Two of Us equally deserving of some remarks, but we choose to conclude with just the “two of us” (2023) —in which a woman walks by the seashore escorted by a large black penguin while a man gazes at her from behind a tree. Another free interpretation of the 1979 Lennon/McCartney song? “Two of us riding nowhere / Spending someone’s hard-earned pay / You and me Sunday driving / Not arriving on our way back home.” Who are the two of us? A man and a woman? It’s not you, it’s me? Two of us who are three? The third being the “someone” in the song’s lyrics? He, she and the penguin? The answer may be bigger than the two of us. The male gaze and the female stare. An artist who proposes a work and a viewer who interprets it, even when the amphibious bird and the blade on the bench remain a mystery. Does Occam’s razor preempt wild interpretations?

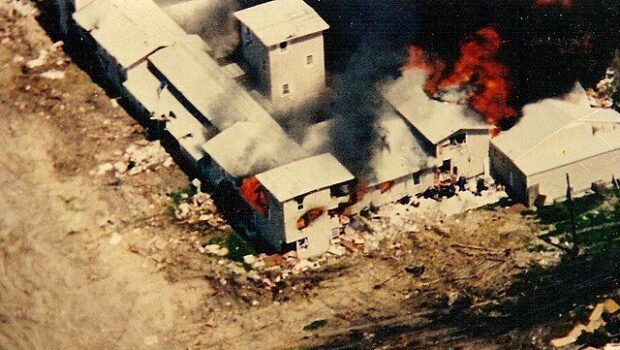

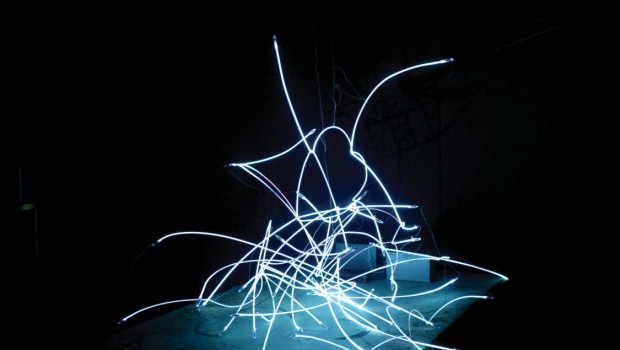

Vinyl music records were the main vehicle for enjoying music for decades. In the late 1980s the advent of compact discs challenged their hegemony; but in 2022 vinyl records sales again surpassed those of CDs. For Two of Us, Gordin made an on-site mural graphite drawing of a black vinyl record four feet in diameter. He carefully depicted the grooves where sound information was stored and retrieved by a stylus, often called “the needle.” On the side A label of Gordin’s generic vinyl record the letters of random titles seem to spiral into the black hole which is the center of an imaginary turntable. With them go the musical memories of those of us who once placed the stylus on the vinyl as carefully as possible so as not to “scratch” it.

Agujero Interior, 2024. On-site Mural by Sebastián Gordin.

- The Abraxas album cover features a 1961 painting Annunciation by German-French painter Mati Klarwein.

- The list of artists who have designed album covers is long: Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Damien Hirst, Salvador Dali, Banksy, etc. There is even a longer list of works of art which have been used as album covers; typically, of so-called classical music.

- Some of the lyrics of “Nowhere man” go: “Doesn’t have a point of view / Knows not where he’s going to / Isn’t he a bit like you and me?

- Video “Los Visuales: Santiago Gordín” in YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XcVMo0ZD0qQ

- The John Lennon / Paul McCartney song “For no one” is included in the 1966 album Revolver.

- Henry Dagg is a sound sculptor and builder of experimental musical instruments. His works include a pin barrel harp (sharpsichord), a pair of musical gates, an artificial cat organ (using squeaky stuffed toy cats), the musical saw, the voicecycle, etc. “Music from the cutting edge” is a 2003 Dagg album in whose cover he is in exactly the same pose as in Gordín’s marquetry.

-

Un homme et une femme (1966) film by Claude Lelouch.

Fernando Castro es artista, crítico y curador. Estudió filosofía en la Universidad de Rice con una beca Fulbright. Es miembro de la comisión técnica del FotoFest y del consejo consultivo del Center for Photography de Houston. Editor y colaborador de las revistas Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal Magaziney Spot.

Fernando Castro es artista, crítico y curador. Estudió filosofía en la Universidad de Rice con una beca Fulbright. Es miembro de la comisión técnica del FotoFest y del consejo consultivo del Center for Photography de Houston. Editor y colaborador de las revistas Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal Magaziney Spot.

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad.

Posted: August 14, 2024 at 8:31 pm