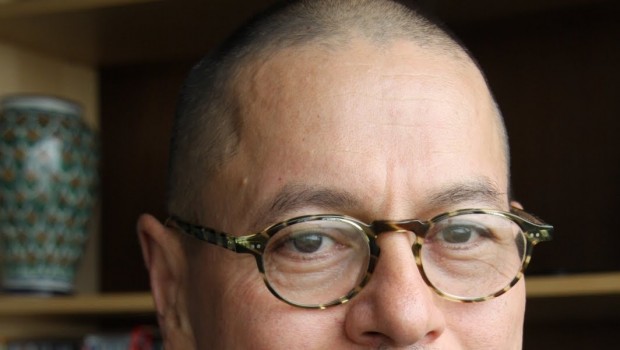

Interview with Michael Nava

Lorena Gauthereau

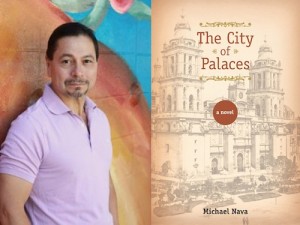

On Thursday, September 25, 2014, acclaimed author and lawyer, Michael Nava presented a reading of his newest novel, The City of Palaces, at Rice University. This new novel marks the beginning of his newest series (The Children of Eve), which takes place in the years before and during the Mexican Revolution. The series will delve into the rise of the Mexican-American silent film star, Ramon Novarro, the Mexican Revolution, and the near-genocide of the Yaqui Indian tribe.

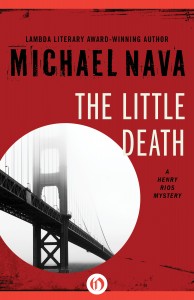

Nava is known for his crime novel series, which is centered on gay Latino criminal defense lawyer, Henry Rios. The series won six Lambda Literary Awards, and in 2001, he received the Bill Whitehead Lifetime Achievement Award in LGBT literature. He is a native Californian and the grandson of Mexican immigrants.

***

Lorena Gauthereau: I see your first novel, The Little Death, came out in 1986. Publishers were just discovering Latina/o writers in the 1980s. What has changed about publishing and Latina/o writers?

Michael Nava: Well, nothing, really. I mean I gave a speech about this in San Antonio last Spring about the Latino literary landscape entitled “White Privilege and Latino/a Literature” about essentially the racism in the New York publishing industry toward our writers. It’s not overt but most of us are published by small presses or university presses, we are not published by the New York commercial houses because they don’t think there’s an audience for our work and that in and of itself is based on racist assumptions about Latinos not being educated, not being readers or consumers of books, and also about white readers not being interested in our experiences, which I think really does a disservice to white readers. It’s very difficult for us to get published in the mainstream and get that mainstream attention.

LG: Chicana/o writers, slowly but surely, seem to be venturing into writing historical novels set in Mexico. Here, I’m thinking about Alicia Gaspar de Alba’s Sor Juana’s Second Dream, Luis Urrea’s The Hummingbird’s Daughter, etc. and now your novel, The City of Palaces. During the Chicano Movement, by contrast, very few things were set in Mexico. What do you think is going on?

LG: Chicana/o writers, slowly but surely, seem to be venturing into writing historical novels set in Mexico. Here, I’m thinking about Alicia Gaspar de Alba’s Sor Juana’s Second Dream, Luis Urrea’s The Hummingbird’s Daughter, etc. and now your novel, The City of Palaces. During the Chicano Movement, by contrast, very few things were set in Mexico. What do you think is going on?

MN: Well, I think as we become more confident in our own identities we want to go back and trace our roots into la patria chica. Certainly, my own family’s history—my great grandparents came to California during the [Mexican] Revolution—goes back to Mexico, so inevitably, being interested in my heritage, I was led back to that country and that period of time. For a long time I think that the Chicano movement was focused on Mexican and Mexican American communities in this country. And now that we’re more mature in our identity, I think we’re looking back, and for me it’s also a matter of educating people, both Anglo readers and Latino readers, about this period of Mexican history.

LG: Thinking about your Henry Rios series and your move to The City of Palaces, what propelled that genre shift?

MN: The Rios books were more of an exploration of being gay. The City of Palaces and the books that I plan to write in that series are more of an exploration of being Mexican. So, that’s really the major difference. And the other thing is I really wanted to recover for myself and my readers, both white and Latino, a very important part of Mexican history that had long-term implications for this country, because as you know the first great wave of Mexican migration occurred as a result of the [Mexican] Revolution, as people streaming into the United States as refugees, almost five hundred thousand. It was the beginning of this great demographic shift that we still see occurring today.

LG: In the Henry Rios series, you didn’t just write a standard whodunit novel, you also sought to dive into Henry’s understanding of self, specifically gay identity politics that go beyond a simplistic understanding of sexuality as a simple physical desire. A line by Henry that I felt particularly powerful was in The Death of Friends, when he thinks about his closeted friend, Chris: “but to me the sacrifice would’ve been of the thing that made me human, the ability to love and to be loved, the drive toward connectedness.” Can we expect similar self-reflection and drive toward connectedness in your new series? And how will if differ given the shifted historical context?

MN: What I write about in my novels, whatever the form may be—mystery or historical novels, those are reductive labels—the underlying theme is the same: it’s about the outsider that learns to embrace his or her identity in the face of social condemnation. And that’s the through line in everything I write. In the Rios books it’s Henry not just accepting his homosexuality, but seeing it as a force of his own personal liberation. The more you accept who you are in all your complexities, the more authentic your life becomes and that continues in this series. All the main characters in The City of Palaces are, for one reason or another, outsiders who have to come to terms with something about themselves that puts them outside the margins of the culture in which they find themselves, and which they learn ultimately empowers them in a way. So, I write not mysteries, not historical novels, I write outsider novels. It’s such a rich and interesting thing to explore.

MN: What I write about in my novels, whatever the form may be—mystery or historical novels, those are reductive labels—the underlying theme is the same: it’s about the outsider that learns to embrace his or her identity in the face of social condemnation. And that’s the through line in everything I write. In the Rios books it’s Henry not just accepting his homosexuality, but seeing it as a force of his own personal liberation. The more you accept who you are in all your complexities, the more authentic your life becomes and that continues in this series. All the main characters in The City of Palaces are, for one reason or another, outsiders who have to come to terms with something about themselves that puts them outside the margins of the culture in which they find themselves, and which they learn ultimately empowers them in a way. So, I write not mysteries, not historical novels, I write outsider novels. It’s such a rich and interesting thing to explore.

LG: You’ve had an interesting career between the law and writing, between being a lawyer and a fiction writer. How has one influenced the other, and where do you go next?

MN: Rios is a criminal defense lawyer and certainly those novels were informed by the work I’ve done as a lawyer because, although I’ve done all sorts of law, I think what has been consistent in 30 years of practice of law is that I’ve done a lot of criminal law, both as a prosecutor and an appellate lawyer. There are court room scenes that I sort of lifted directly from my own experience as a court room lawyer. And in the lawyers in my novels I’m concerned with outsider status. Part of what I’ve done in the last ten years is mentor law students of color, undergraduates of color who want to become lawyers, and help them overcome the obstacles that prevent us from advancing in the legal profession. So I think that’s been pretty consistent with what I think my life’s mission has been. What’s next? Well, I’m going to retire from the law in a couple of years, which I’m really looking forward to so that I can devote myself more to writing and associated pursuits.

LG: Anything else you would like to add?

MN: I hope to live long enough to finish the four novels I have planned!

Posted: October 1, 2014 at 5:11 am