The Persistence of Memory: A Conversation with Mario Vargas Llosa

La memoria pertinaz

Miguel Ángel Zapata

Translated to English by Rose Shapiro

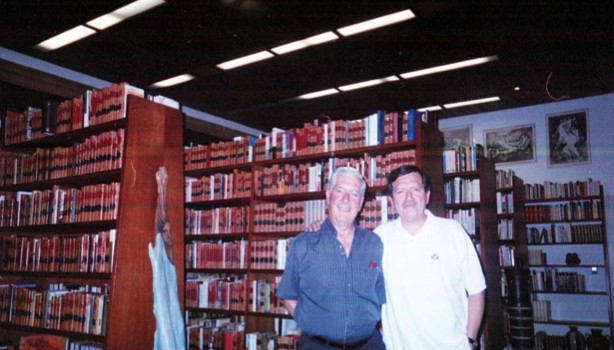

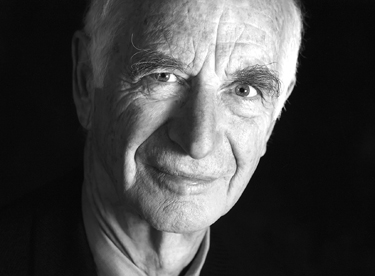

Mario Vargas Llosa (Arequipa, Peru, 1936) spends part of every year in Lima, Madrid, Paris, and London. This summer I had the good fortune to meet with him in his house overlooking the sea in Barranco (Lima), where we spoke for a while by the azure sea of the Lima coast. Mario Vargas Llosa is perhaps the most talented contemporary Latin American novelist, and many of his novels are now classics.

Every one of his novels or other writings is a discovery; he never repeats himself. His novelistic oeuvre is evenly masterful, accompanied by a notable body of essays, chronicles, and dramatic works. His most recent book,The Temptation of the Impossible: Victor Hugo y Les Miserables (Alfaguara, Madrid, 2004), is a brilliant study ofLes Miserables, from the point of view of a writer who truly knows his craft. Among his works we can mentionThe Bosses, The City and the Dogs, The Green House, Conversation in the Cathedral, Pantaleon and the Visitors, Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter, The War at the End of the World, The Real Life of Mayta, Who Killed Palomino Molero?, The Storyteller, In Praise of the Stepmother, Death in the Andes, The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto, The Feast of the Goat, and The Way to Paradise: A Novel. In 2002 he received the Pen/Nabokov Prize, and in 2004 the Premio Grinzane Cavour (Turin, Italia). To listen to Mario is always a great intellectual experience.

* * *

Miguel Ángel Zapata: Mario, with this beautiful view that you have here I could write a poem every day.

Mario Vargas Llosa: Yes, of course, but I couldn’t write a novel a day, although I can certainly progress a little bit every day in whatever novel I am working on.

M. A. Z.: Then you would say quite definitely that the environment—one’s surroundings, nature itself—supports the process of writing and creating?

M. V. LL.: Without a doubt. Yet I also believe that when you are obsessed with a story you write in the same mode regardless of your surroundings. A pleasant environment, like this one for example—a lovely landscape in constant change, because the sea in the morning is not the same as the sea at twilight, not the same as the sea when it is sunny or cloudy—is not only pleasing to me but also stimulating.

M. A. Z.: You live in different countries. How are you able to continue working as you move around?

M. V. LL.: Indeed, my residence changes; I live in Lima, Madrid, London, and Paris. What is stable—rather, what gives great stability to my life— is my work, because I never stop working. I leave Lima and arrive in Paris, and the next day I take up the work where I left it in Lima, and it is the same when I go from Lima to Madrid to Paris or to London. In each city I come to a desk where I have absolutely everything I need to work: diskettes, index cards, the indispensable books that I feel I must take with me wherever I go. My routine is always the same: I begin work in the morning and continue in the afternoon, and this has not changed in a very long time. The truth is that it was a different story when, in addition to writing, I had to work to make a living, but since I have been able to devote all of time to writing my routine is the same. In the morning my work is more creative; in the afternoon I correct, reread, and take notes for the following day’s work. In the afternoon I always do research, which complements the creative work. I respect that routine rigorously. I work during the week on the book I’m writing, and on the weekends I devote my time to writing articles; I write newspaper articles a couple of times a month.

M. A. Z.: What is the point of departure for your writing?

M. V. LL.: Generally speaking, the point of departure is memory; I believe all the stories I have written have been born of some lived experience that has remained in my memory and that becomes an image, fertile ground for imagining a whole structure around it. It’s also true that I have always followed an outline, almost since my first story: I take many notes, I make index cards, and I make some plot sketches before beginning to compose. In order to be able to begin writing I need at least a structure, though perhaps a very general one, for the story. And then I can begin to work. I first produce a draft, which is the part of the work that is hardest for me. As soon as I have it the work is much more pleasant; I can write more confidently, more securely, because I know that the story is there. This has been a constant in what I have written: doing research that will familiarize me with the theme, the situation, the period during which the story takes place.

M. A. Z.: As is the case with your novel about Flora Tristán and Paul Gaugin.

M. V. LL.: No doubt. Of course, that work dealt with historical personalities, but in other cases, although I’m not working with a historical situation, I anyway travel to the places where the story takes place, I read testimonies, newspapers of the period, not with the aim of reproducing a historical truth but rather to feel familiar with, immersed in, the environment in which I want to situate the characters and the story. Then I correct a lot, rewrite a lot. For me, to tell you the truth—this is something José Emilio Pacheco once said, and it seems right on the mark to me—what I like best is not writing but revising. It’s the absolute truth. When I correct and revise what I have already done, that is when I really enjoy writing the most.

M. A. Z.: And when you finish a novel and it’s published, do you read it again? To look for faults, perhaps, I don’t know. . .

M. V. LL.: No. The last time that I read it is in proofs, and after that I try not to read it again, if I can help it. Sometimes when I work with a translator I am obligated to reread in order to correct errors, but in general I don’t like to revisit what I’ve already written and published.

M. A. Z.: But perhaps you’ve read a fragment and thought that you would have liked to change a section of the novel, as was the case with Valéry, Juan Ramón Jimenez, and now with Pacheco, whose brilliant poetry is in a continual state of revision.

M. V. LL.: Of course, that has happened to me often, and it is one of the reasons I don’t like to reread my own work once it’s published. Every time that I reread my own work I wonder whether I could have worked on the story a little bit more.

M. A. Z.: What are your favorite books?

M. V. LL.: Well, here we go. They would be Madame Bovary, several of Flaubert; I would also choose Faulkner’s Light in August and perhaps Sanctuary, Melville’s Moby-Dick, Tolstoy’s War and Peace, Balzac’sScenes from a Courtesan’s Life, Joyce’s Ulysses, Cervantes’s Quixote, and Tirant lo Blanc, which was very important to me because it gave me the idea of the novel as a totality, a world unto itself. Well, I could choose hundreds of titles.

M. A. Z.: Do you read poetry?

M. V. LL.: I do. I tend to reread many of the authors who have most impressed me, starting with Rubén Darío, who is these days not so often read and who I still think remains the father, the magical master, of true poetry in Spanish. I also reread Neruda, whom I loved in my youth, and Baudelaire, perhaps the poet I admire most among all poets. I like Eliot very much, not only as a poet but also as an essayist.

M. A. Z.: So Baudelaire has moved you greatly; poetry also influences prose writers.

M. V. LL.: Yes, Baudelaire, most definitely, but also all the authors I have read and who have moved me and caused me to think deeply, who have greatly influenced who I am, my sensibility. But, now, how could one follow in the footsteps of an author like Joseph Conrad? In fact, right now I’m rereading Conrad.

M. A. Z.: Which works of his are you rereading?

M. V. LL.: Last year I reread Lord Jim, which struck me as a masterpiece, extraordinary; but, on the other hand, I picked up Nostromo, and I find it a description of a Latin America full of quaintness, clichés, and commonplaces. It’s the first time that one of Conrad’s novels has disappointed me.

M. A. Z.: Do you still feel the same way about José María Arguedas as you did in your book La utopía arcaica?

M. V. LL.: Yes. I believe that Arguedas was an extraordinary case in Peruvian literature, because of his roots in two cultures, both of which he came to know and experience profoundly, from within. This gave him a vision of Peru that only with great difficulty do other Peruvian writers accomplish, since they lack that experience of two worlds. I think Arguedas wrote a great novel, Los ríos profundos, into which he poured his experience of two cultures, the vision of a self-sufficient world created from a historical and social reality but utterly transformed into art, thanks to a language, a sensibility. I don’t think he achieved the perfection of Los ríos profundos in his later work, although he wrote some very lovely stories. In those novels he failed not for literary reasons but for sociological and ethnological ones, as is the case with El zorro de arriba y el zorro de abajo.

M. A. Z.: A novel he never finished…

M. V. LL.: He left it almost finished, and in all of his work Arguedas shows himself to be a writer who clearly wants to represent a state of affairs very graphically. Certainly, he is the Peruvian writer that I have read and reread most often. Arguedas is interesting not only as a writer but also as a uniquely positioned witness to the drama of our country—the drama of discovered and conquered cultures— and of the bipolarity of Peruvian society, and his testimony is genuine and authentic. Arguedas has meaning for Peru that goes beyond the purely literary.

M. A. Z.: Let’s speak for a bit now about fiction and autobiography. In Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter or in El hablador do you appear as a camouflaged character?

M. V. LL.: No. Sometimes someone appears who has my name and in other ways takes advantage of experiences that I have had, but he always appears in a context and living experiences that are much more diverse than those I have had, such that none of my novels is exclusively autobiographical, not even the one that most seems to be, which is Aunt Julia. Sure, in that case I took advantage of a moment in my own life, but even in the story of Varguitas, who would have liked to have been a writer, there is much more imagination that personal memory. Autobiography is a literary resource, as in El hablador.

M. A. Z.: How do you transform this aspect; that is, how do you make the autobiographical into the literary?

M. V. LL.: Biographical facts are subsumed in imagined, or, as you put it, transformed facts. In the end, that which is imagined wins out. Now, if you are asking me whether literature has an autobiographical source, I would say so; I can’t help but believe that the point of departure is always memory: you get images from memory, images that have been with you a long time, and that is the primary material with which a writer works. But it is a primary material from which you depart in order to create a world. I don’t think this experience is very different from that of the poet. The poet also starts from memory, from an experience of life, of people, of reality as it is constructed in remembrance.

M. A. Z.: Let’s turn to the critics of your work. Whom would you mention as those who have hit the mark in their approaches to your writing?

M. V. LL.: David Gallagher wrote an essay about Conversation in the Cathedral that really surprised me; what I remember most of all is the idea—I think it’s more or less like this—that that novel shows that power is dirty and that every time the novel dealt with the theme of power its prose style itself became dirty; that is, he pointed out that the all aspects of the novel in some ways reflect what the novel is trying to argue. Also José Miguel Oviedo has made some very serious and rigorous analyses of, above all, structures and techniques in my work, and I have learned a lot from his approaches. Finally, Efraín Kristal’s book was a revelation for me. He reads practically all of the books that I have said influenced me and finds in those books many sources and models that I have in some way used in my work. It is one of the books that has interested me most and been most instructive in terms of showing me how I proceed; and it taught me that as much as one works rationally and systematically on one’s stories, as I do, one does not have the necessary critical distance to know exactly what one is doing on paper.

M. A. Z.: What can you say about the Peruvian poets who interest you and whom you read?

M. V. LL.: Vallejo, of course. And César Moro, of whom I was an early reader, back when no one knew who he was. I started reading him upon his death, inspired by a very dramatic essay by André Coyné, and since that moment I began looking for his work, and I even helped published some of his unpublished work. I have been a very devoted reader of Peruvian poetry, during all the years I have lived in Peru, and a very enthusiastic one, as well. For instance, I wrote an essay about our great poet Carlos Germán Belli.

M. A. Z.: A few words about politics in Peru. Do you agree that President Toledo should be allowed to finish his term in office (as the constitution mandates), or should we listen to his enemies, those who do not want him to finish his term?

M. V. LL.: Yes, I believe he should finish his term and that the constitutional terms of office should be maintained. We have a very fragile democracy, and the worst way to preserve it is to change the rules of the game, or to change the procedures that are fundamental to a democracy. Now, while there are many reasons to criticize this government, there have also been many indisputably good moves, ones that no one recognizes— for example, the situation of Peru with respect to the rest of Latin America—. Peru has likely been the country that has progressed the most in the past few years in terms of economic development.

M. A. Z.: What do you think of the recent taking of the police station of Andahuayalas by Antauro Humala and the etnocaceristas?

M. V. LL.: It is a display of primitivism, of underdevelopment, and of stupidity. It involves only a small group. Unfortunately, there is such a hostile climate, with so much belligerence towards the government and established institutions, that in the wake of Humala we find considerable animosity, which turns out to be very deceptive. The surveys indicate that Humala has 34% to 40% support in Peru; I don’t believe it. What happens is that discontent finds a way to manifest itself, and thus we see its identification with extreme nationalism, racism, and other of Humala’s idiocies.

M. A. Z.: That group and others have had a lot to say recently about Chile’s penetration in Peru…

M. V. LL.: I think the worst thing we could do is to fall into the anti-Chile rhetoric that a group of ill-intentioned demagogues is spouting, because generally those who rail against Chile are those who are committed to the dictatorship of Fujimori, many of them accused of thievery and corruption. Most certainly, that business is a smokescreen so that in the ensuing chaos they might be able to get away with their own mischief. The War of the Pacific happened a long time ago, and the worst thing we could do is to keep looking to that unfortunate war, in which of course Peru and Bolivia were the sacrificial lambs. Wars that were fought a century ago must not create enmity between peoples; wars are often conflicts created by governments or by the interests that are the only ones who benefit from these conflicts; the people are always those who pay.

M. A. Z.: Nationalism is one of the worst defects, don’t you think?

M. V. LL.: Of course. Nationalism, in its various forms, has impoverished us and made us more underdeveloped, and it has therefore been the reason regional treaties have never worked in spite of the great efforts to create pacts or common markets. We must combat nationalism. It is a blessing that not only Chilean but also Brazilian, Colombian, and Ecuadorian capital is coming to Peru, to develop our sources of wealth, since in the end the rules of the game are set not by them but by our governments. Now, if the government is inept and corrupt, naturally those investments are coming to Peru under very unfavourable conditions. Therefore we must demand transparency and honesty of our government.

M. A. Z.: This government has not been transparent.

M. V. LL.: Of course not. I think there are, unfortunately, many corrupt people in this government, and I think one of Toledo’s most serious errors was to surround himself with untrustworthy people. It is one of the things that have most damaged his popular image and that has allowed his enemies to attack his administration. Among those untrustworthy people are of course many corrupt characters from Fujimori’s administration, who moreover have control over the media and who are full of poison and hate and who try to create chaos by all means possible in order to evade condemnation and the rule of law.

M. A. Z.: What literary project are you pursuing now?

M. V. LL.: I am in the midst of writing a novel, which I started after finishing my essay on Victor Hugo.

M. A. Z.: What is it about?

M. V. LL.: It’s a novel that is constructed as a series of short stories; every chapter is a story that can be read independently and, at the same time, as a chapter of a novel that encompasses all the stories. Each one of these stories occurs in a different city and a different period, which indeed allows me to make use of my own experience of the cities in which I have lived—but other than that it’s not at all autobiographical—.

M. A. Z.: Do you already have a title for it?

M. V. LL.: Yes. Travesuras de la niña mala. Do you like it?

M. A. Z.: I love it. It would be perhaps the first title of yours to manifest your discourse on the erotic.

M. V. LL.: It’s a provisional title, of course, but there we are…

Mario Vargas Llosa (Arequipa, Perú, 1936) vive cada año entre Lima, Madrid, París y Londres. Este verano tuve la suerte de encontrarlo en su casa del malecón de Barranco, donde conversamos un rato frente al mar azulino de la costa limeña. Mario Vargas Llosa es tal vez el novelista latinoamericano más talentoso en la actualidad, demostrable al leer sus ya clásicas novelas.

Cada novela o escrito suyo es un nuevo descubrimiento, nada se repite. Tiene una obra novelística sumamente pareja, acompañada por una notable obra ensayística, además de crónicas y obras de teatro. Su libro más reciente, La tentación de lo imposible. Victor Hugo y Los miserables (Alfaguara, Madrid, 2004) es un lúcido estudio de Los miserables, desde la mirada de un escritor que conoce bien su oficio. Entre sus obras se pueden mencionar Los jefes, La ciudad y los perros, La casa verde, Conversación en la catedral, Pantaleón y las visitadoras, La tía Julia y el escribidor, La guerra del fin del mundo, Historia de Mayta, ¿Quién mató a Palomino Molero?, EL hablador, Elogio de la madrastra, Lituma en los Andes, Los cuadernos de don Rigoberto, La fiesta del chivo, y El paraíso en la otra esquina. En el 2002 recibió el Premio PEN/Nabokov y en el 2004 el Premio Internacional Una Vida para la Literatura (Premios Grinzane Cavour). Escuchar a Mario es siempre una muy grata experiencia intelectual.

* * *

Miguel Ángel Zapata: Mario, con esta vista preciosa que tienes aquí yo podría escribir un poema todos los días…

Mario Vargas Llosa: Sí claro, pero yo no podría escribir una novela todos los días, aunque sí podría avanzar algo en una novela todos los días.

M. A. Z.: Entonces definitivamente el ambiente, el entorno, la naturaleza sí ayuda en el proceso de escribir y de crear.

M. V. LL.: Sin ninguna duda. Hombre, yo creo que cuando tú estás obsesionado con una historia escribes igual sea cual sea el entorno. Un ambiente agradable, como éste por ejemplo, que es un paisaje cambiante y bonito, porque ver el mar en la mañana no es lo mismo que verlo a la hora del crepúsculo, no es lo mismo que verlo con sol o nublado, a mí me resulta no sólo grato sino también estimulante.

M. A. Z.: Tú vives en distintos países ¿cómo haces para continuar con tus trabajos al cambiar de espacios?

M. V. LL.: Efectivamente, digamos mis residencias son cambiantes, Lima, Madrid, Londres y París. Lo que es estable, o, mejor dicho, lo que da una gran estabilidad a mi vida es mi trabajo, porque yo no paro nunca de trabajar. Salgo de Lima, llego a París y al día siguiente retomo, continúo el trabajo donde lo dejé en Lima, y me pasa exactamente lo mismo cuando paso de Lima a Madrid a París o a Londres. Llego a un escritorio donde tengo absolutamente las cosas que necesito para trabajar, los disquetes, las tarjetas, los libros indispensables con los que tengo que desplazarme. Mis rutinas son las mismas, trabajo mañana y tarde, comienzo en las mañanas, y esto no ha cambiado desde hace muchísimo tiempo. La verdad es que cuando, además de escribir, tenía trabajos alimenticios, era distinto, pero desde que pude dedicarme fundamentalmente a escribir mi rutina es la misma, durante la mañana de una manera más creativa, en la tarde corrigiendo, releyendo, tomando notas para el trabajo del día siguiente. En las tardes hago siempre la investigación, me acompaña siempre como algo complementario al trabajo creativo. Esa rutina la respeto rigurosamente. Trabajo durante la semana en el libro que estoy escribiendo, y los fines de semana los dedico a los artículos, porque escribo artículos periodísticos un par de veces al mes.

M. A. Z.: ¿Cuál es el punto de partida de tu escritura?

M. V. LL.: Generalmente el punto de partida es la memoria; creo que todas las historias que he escrito han nacido siempre como fruto de alguna vivencia que ha quedado en la memoria y que se convierte en una imagen muy fértil para fantasear algo alrededor de ella. Ése ha sido casi siempre el punto de partida de todo lo que he escrito.

También he seguido una pauta, prácticamente desde el primer cuento que escribí: tomo muchas notas, hago fichas, hago unos esquemas antes de empezar a redactar. Para poder comenzar a escribir necesito por lo menos una estructura aunque sea muy general de la historia. Y luego pues comienzo a trabajar. Hago primero un borrador, que es lo que más trabajo me cuesta. Una vez que lo tengo para mí el trabajo es mucho más agradable, ya escribo de una manera más confiada, más segura, porque sé que la historia está allí. Esto ha sido una constante en lo que he escrito: hacer una investigación que me familiarice con el tema, la situación, la época en la que está situada la historia.

M. A. Z.: Es el caso de Flora Tristán y Paul Gauguin.

M. V. LL.: Sin ninguna duda. Claro, se trataba de dos personajes históricos, pero en otros casos aunque no es un tema histórico, pues viajo a los sitios donde ocurre la historia, leo testimonios, periódicos de la época, pero no con un afán de reproducir una verdad histórica, sino para sentirme familiarizado, contaminado del medio en el que yo quiero situar los personajes y la anécdota. Luego corrijo mucho, rehago mucho. Para mí en realidad —eso lo dijo una vez José Emilio Pacheco— me pareció muy exacto, lo que me gusta más no es escribir sino re-escribir. Es la pura verdad. Cuando corrijo y rehago lo que he hecho, es cuando realmente gozo más escribiendo.

M. A. Z.: Y cuando terminas una novela, y sale publicada ¿la vuelves a leer? Buscar tal vez carencias, no sé…

M. V. LL.: No. La última vez que la leo es en las pruebas, y después no, procuro no leerlas. A veces lo hago cuando trabajo con algún traductor y releo obligado para corregir erratas, pero en general no me gusta volver sobre lo escrito y publicado.

M. A. Z.: Pero tal vez hayas leído un fragmento… y quizá hayas pensando que te hubiese gustado cambiar cierta sección de la novela, como sucedía en poesía con Valéry, Juan Ramón Jiménez, y ahora con Pacheco, cuya lúcida poesía es un continuo corregir…

M. V. LL.: Claro, me ha pasado siempre, y es una de las razones por las cuales no me gusta releerme, cada vez que me releo pienso que hubiera podido trabajar la historia un poquito más…

M. A. Z.: José Emilio corrige sus poemas ya publicados en nuevas ediciones, eso es saludable en el caso de la poesía…

M. V. LL.: Yo en cambio a diferencia de Pacheco hago sólo correcciones de erratas pero no del texto ya publicado.

M. A. Z.: ¿Cuáles son tus libros predilectos?

M. V. LL.: Pues mira, serían Madame Bovary, varias de Flaubert, elegiría, Luz de agosto, quizás Santuario, de Faulkner, Moby-Dick, de Melville, La guerra y la paz, de Tolstoi, Esplendor y miseria de cortesanas de Balzac,Ulises de Joyce, El Quijote de Cervantes, Tirant lo Blanc, que para mí fue importantísimo, ya que me dio la idea de la novela como una totalidad, o sea como un mundo cerrado sobre sí mismo, en fin, elegiría cientos de títulos…

M. A. Z.: ¿Lees Poesía?

M. V. LL.: Leo poesía, releo mucho a los autores que a mí me han impresionado, empezando por Rubén Darío, que ya casi no se lee mucho, y que sigo creyendo que sigue siendo el padre, el maestro mágico de la verdadera poesía en español, releo a Neruda que fue un amor de juventud, Baudelaire, quizás el poeta que admiro más entre todos los poetas, a Eliot que me gusta muchísimo, no sólo como poeta sino también como ensayista.

M. A. Z.: Entonces Baudelaire te ha estremecido, porque la poesía también influye en los escritores de prosa, ¿no?

M. V. LL.: Si claro él, pero también todos los autores que he leído y que me han hecho estremecer, y me han llevado a reflexionar y han gravitado sobre lo que yo soy, sobre mi sensibilidad, ahora, cómo se puede digamos seguir, rastrear a un autor como Joseph Conrad, justamente ahora estoy releyendo a Conrad…

M. A. Z.: ¿Qué estás releyendo de él?

M. V. LL.: El año pasado releí Lord Jim, me pareció una obra maestra, extraordinaria, pero por otro lado, empiezo a leer Nostromo, y me ha parecido una descripción de una América Latina llena de pintoresquismo, de clichés, de lugares comunes. Es la primera vez que me decepciona una novela de Conrad.

M. A. Z.: Cambiando de latitudes, ¿sigues viendo a José María Arguedas como en tu libro La utopía arcaica?

M. V. LL.: Sí. Creo que Arguedas fue un caso extraordinario en la literatura peruana por su enraizamiento en dos culturas, las cuales llegó a conocer y vivir profundamente, desde adentro. Esto le dio una visión del Perú que muy difícilmente tienen los escritores peruanos, ya que carecen de ese tipo de experiencia. Creo que Arguedas escribió una gran novela, Los ríos profundos, donde volcó su experiencia de dos culturas, la visión de un mundo autosuficiente creado a partir de una realidad histórica y social pero completamente trasmutada en arte, gracias a una lengua, a una sensibilidad. Después no creo que llegó a alcanzar la perfección de Los ríos profundos, aunque escribió relatos que son muy lindos. En estas novelas fracasó, por razones no literarias, sino por razones de tipo sociológico, etnológico, como es el caso de El zorro de arriba y el zorro de abajo.

M. A. Z.: Novela que no terminó…

M. V. LL.: Se quedó en una versión muy avanzada, pero todo Arguedas es un escritor muy representativo de un estado de cosas, dramático, seguramente es el escritor peruano que he leído y releído más… El caso de Arguedas no sólo es interesante como escritor sino como un testigo privilegiado de nuestro país, del drama de las culturas encontradas y sometidas, de la bipolaridad de la sociedad peruana, y su testimonio es genuino y auténtico. Su persona tiene una significación que desborda lo puramente literario.

M. A. Z.: Hablemos un poco ahora de la ficción y lo autobiográfico. En La tía Julia y el escribidor, o en El hablador, ¿apareces tú como personaje camuflado?

M. V. LL.: No, aparece un ser que a veces lleva mi nombre y en otros casos aprovecha de experiencias que yo he tenido, pero aparece siempre dentro de un contexto y viviendo experiencias que son mucho mas diversas de las que yo he tenido, de tal manera que ninguna de mis novelas es exclusivamente autobiográfica, ni siquiera la que lo parece más, como esLa tía Julia… Claro, ahí he aprovechado un momento de mi vida, pero incluso en la historia del varguitas que quisiera ser un escritor, hay mucho mas de invención que de memoria personal, la autobiografía es un recurso literario, como en El hablador…

M. A. Z.: ¿Cómo fantaseas este aspecto?

M. V. LL.: Los datos biográficos están disueltos en datos inventados, fantaseados, como dices. Al final todo esto último, lo inventado termina prevaleciendo. Ahora, si me preguntas si la literatura tiene una raíz autobiográfica, creo que sí, inevitablemente creo que el punto de partida es siempre la memoria: hay unas imágenes que te da la memoria, que te han acompañado mucho tiempo, y ésa es la materia prima con la que trabaja un escritor. Pero es una materia prima desde donde partes para construir un mundo. No creo que sea una experiencia muy distinta de la del poeta, el poeta también parte de una memoria, de una vivencia de la vida, de la gente, de la realidad conservada a base de recuerdos.

M. A. Z.: ¿Crees que existe una literatura latinoamericana judía fuerte, una presencia, como es el caso de La vida a plazos de don Jacobo Lerner de Isaac Goldemberg?

M. V. LL.: La vida a plazos me parece una magnífica novela. Por otro lado yo he tenido un interés en Israel por razones políticas no religiosas, y fue una experiencia maravillosa la que tuve en Israel. Pero nunca he leído a un escritor por su raza o su religión ni siquiera por sus convicciones políticas. A los creadores los leo por su talento simplemente, y el talento se da en cualquier aspecto cultural, como es el caso de Kafka.

M. A. Z.: Y ahora hablando de los críticos de tu obra, ¿a quiénes mencionarías como los que han acertado en sus aproximaciones?

M. V. LL.: David Gallagher, escribió un ensayo sobreConversación en la catedral, que para mí fue muy sorprendente, recuerdo sobre todo una idea, decía… más o menos así… en esa novela se demuestra que el poder es sucio, y la prosa de la novela cada vez que se acerca al poder se ensucia, o sea que la novela de alguna manera somatiza lo que la novela quiere mostrar. También José Miguel Oviedo ha hecho unos análisis muy serios, rigurosos, sobre todo de las estructuras, de las técnicas, y he aprendido de sus acercamientos. Por último, el libro de Efraín Kristal fue muy revelador para mí, él relee prácticamente los libros que yo he dicho que me han impresionado, y entonces encuentra en esos libros muchas fuentes, muchos modelos que yo he aprovechado. Es uno de los libros que me ha interesado más y que ha sido muy instructivo sobre lo que yo hago, y me ha demostrado que por más que uno trabaje muy racionalmente como lo hago yo preparando sus historias, uno no tiene la distancia suficiente para saber exactamente lo que uno hace en el papel.

M. A. Z.: ¿Qué me dices de los poetas peruanos que te interesan y que lees?

M. V. LL.: Vallejo, por supuesto, César Moro, del cual fui un lector precoz cuando nadie lo conocía, lo leí a raíz de su muerte, y a raíz de un ensayo muy dramático de André Coyné, y desde esa vez comencé a buscar cosas de él, e incluso ayudé a publicar libros inéditos de César Moro. He sido un lector muy devoto de la poesía peruana, sobre todos los años que viví en el Perú; fui un lector muy entusiasta e incluso escribí un ensayo sobre Carlos Germán Belli.

M. A. Z.: Un poco sobre la política en el Perú. ¿Estarías de acuerdo en que se deba dejar al presidente Toledo terminar su mandato (como lo señala la constitución) o hacer caso a sus enemigos que no lo quieren dejar que culmine su periodo de gobierno?

M. V. LL.: Sí pienso que debe terminar su mandato y que se mantengan los plazos constitucionales. Nosotros tenemos una democracia muy frágil, y la peor manera de conservarla es alterar las reglas del juego, o cambiar las formas, que es lo fundamental en una democracia. Ahora bien, aunque hay muchas razones para criticar este gobierno, como son los casos de corrupción, también ha habido muchos aciertos que son indiscutibles, que nadie reconoce, por ejemplo la situación del Perú en América Latina. Probablemente el Perú sea el país que ha progresado más en los últimos años en el campo económico.

M. A. Z.: ¿Qué piensas de la reciente toma de la comisaría de Andahuaylas por Antauro Humala y los etnocaceristas?

M. V. LL.: Es una muestra de primitivismo, de subdesarrollo y de estupidez. Se trata de un pequeño grupo. Desgraciadamente hay un clima tan hostil, de tanta beligerancia contra el gobierno y contra todas las instituciones establecidas, que detrás de Humala se ha volcado todo un estado de ánimo que resulta muy engañoso, las encuestas indican que ha habido un apoyo de 34% o 40% de apoyo a Humala. Yo no lo creo. Ocurre que el descontento busca cómo manifestarse y de ahí su identificación con el ultra nacionalismo, el racismo y demás idioteces de Humala.

M. A. Z.: Ellos y otros grupos han hablado mucho recientemente de la penetración chilena en el Perú…

M. V. LL.: Yo creo que lo peor que podríamos hacer es caer en el antichilenismo que están agitando un grupo de demagogos malintencionados porque generalmente los que agitan el antichilenismo son gente que está comprometida con la dictadura de Fujimori, muchos de ellos con juicios por ladrones y por corruptos. Clarísimamente se trata de una cortina de humo para ver si en el caos que se quiere crear se salen con la suya. La guerra del Pacífico ocurrió hace mucho tiempo, y lo peor que podríamos hacer es seguir con los ojos fijos en esa guerra lamentable en la que, por supuesto, Perú y Bolivia fueron los sacrificados. Eso quedó atrás y las guerras de hace un siglo no pueden enemistar a los pueblos, las guerras muchas veces son conflictos creados por los gobiernos o los intereses creados exclusivamente para su beneficio y siempre el sacrificado es el pueblo.

M. A. Z.: ¿El nacionalismo es una de las peores taras, no te parece?

M. V. LL.: Claro. Los nacionalismos nos han empobrecido, atrasado, por eso han sido la razón por la cual nunca han funcionado los tratados regionales, los grandes intentos de crear los pactos o mercados comunes.

Hay que combatir el nacionalismo. Es una bendición que vengan capitales no sólo chilenos, sino también brasileños, colombianos, o ecuatorianos, para desarrollar nuestras riquezas, ya que por último las reglas del juego no las fijan ellos sino nuestros gobiernos.

Ahora si el gobierno es inepto y corrupto naturalmente van a venir en condiciones desfavorables para el Perú, entonces hay que exigir limpieza, transparencia y honestidad a nuestro gobierno.

M. A. Z.: Este gobierno no está siendo transparente…

M. V. LL: Claro que no. Pienso que hay muchos corruptos en este gobierno por desgracia, y creo que uno de los grandes errores de Toledo fue rodearse de gente poco confiable. Es una de las cosas que más lo ha perjudicado en la imagen popular, lo que ha permitido que sus enemigos ataquen su gobierno. Entre ellos se encuentran por supuesto muchos corruptos del fujimorato, que además tienen los medios de comunicación, están llenos de veneno, de odio, y tratan de crear caos por todos los medios, para poder librarse de las condenas y los juicios.

M. A. Z.: ¿En qué proyecto literario andas ahora Mario?

M. V. LL.: Ando metido en una novela, después de terminar el ensayo de Víctor Hugo.

M. A. Z.: ¿De qué se trata?

M. V. LL.: Es una novela que está construida por una sucesión de cuentos, cada capítulo es un relato y se puede leer como un relato independiente y, al mismo tiempo, como capítulo de una historia que los engloba a todos estos relatos. Cada uno de esos relatos ocurre en una ciudad y en una época distinta en lo que sí aprovecho mi propia experiencia, en las ciudades en las que viví; en fin, en lo demás no es autobiográfica en absoluto…

M. A. Z.: ¿Ya tienes título?

M. V. LL.: Sí: Travesuras de la niña mala

M. V. LL.: ¿Te gusta ese título?

M. A. Z.: Me encanta. Sería tal vez el primer título de esas novelas donde sí se manifiesta tu discurso erótico.

M. V. LL.: Es un título provisional, claro, pero ahí estamos…