Splendor of the Everyday

Esplendor de lo cotidiano

Fernando González Gortázar

When I mention Gustavo Pérez’s name, people ask me who he is. And, it may be this way in some cases, but some I assume should be aware of him.

The matter in question is ridiculous: Gustavo Pérez is one of our greatest artists. Several things explain this lack of awareness, but perhaps the most important is simply that Gustavo Pérez is a ceramist. We cannot entirely blame the public: ceramics is a field in which the boundaries between a “minor art” and simply Art are particularly obscured. Gustavo always emphasizes his position as an artisan; a great artisan, I might add, a wise and creative technician.

Faithful to this calling, delighted with the craftsmanship of his work, with working on his potter’s wheel, with the skilled production of paper thin vessels, with obsessive details on his pots, plates and bowls, Pérez continues to produce magnificent utilitarian objects and I believe he will never stop making them. I have the impression that for him it is a moral imperative—Gustavo is profoundly concerned with ethical questions— giving minute magnificence to the everyday.

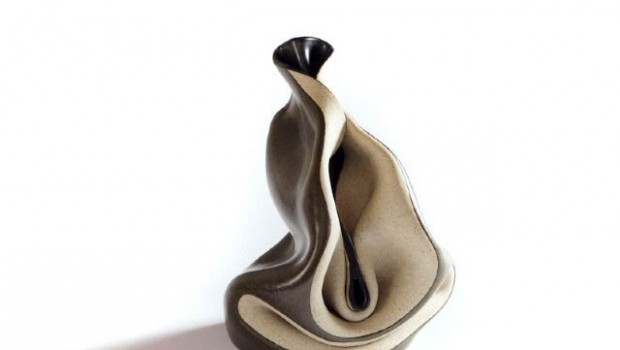

Splendor, yes, and beauty; Gustavo has discovered how an incised line on a clay wall can open up when pressed from inside, like an amazing feminine genitalia. His undulating vessels, furrowed with an endless variety of lines, his indispensable style, his ceaseless questioning of textures and high-temperature glazes, his status as a tireless artisan, inventive and inquiring, has brought new luster to this country’s diminished ancestry of old ceramists.

Almost grudgingly and, almost under protest —fortunately of course!—Gustavo proved himself capable of avoiding all those trends and discoveries gaining autonomy and emerging in pieces in which pure creativity with the medium was the raison d’être; here the highest form of Art seizes the stage.

Entering Gustavo Pérez’s studio, in his Coatepequean paradise, is like entering a laboratory of contemplation and play. On high shelves clean and arranged, sit the “drafts” from which this amazing artist must mine his finished pieces. Occasionally, the objects are no bigger than two or three centimeters: the clay is compressed, hollowed out, pulled, and woven into intricate three-dimensional spider webs. A pinch of the clay can bring about astonishing results, as long as Gustavo Pérez himself makes the modification. The clay of these diminutive objects is like pollen that carries the promise of mature trees. Gustavo’s ceramic sculptures proudly respect the dictates of his primary material: they can be formed only from mud. The naturalness of his crinkles, the bands that form them, his smooth or granular surfaces, irregularly or neatly covered with projections and recesses, everything speaks to the artists’ understanding and absolute respect for his means of expression. Sometimes, a traditionally turned vessel breaks, it frays, it twists or it is repaired and this transformation takes us from the cupboard to the museum, without impeding it from belonging to the cupboard. With these useless (or unusable) pieces, Gustavo changes them into an exceptional standard- bearer of recent Mexican sculpture.

In many of his pieces, Gustavo Pérez delights—with a Benedictine patience—in covering the surfaces with lovely, multicolor and complex designs. The firmness of his lines startles us with their grace, delicacy and variety. The clay is carpeted with scarifications, with irregular and segmented lines, with polychromy and fascinating rhythms. And, he delights in the geometry that transforms itself into stars and constellations that appear to move in the festive air which would have pleased Paul Klee and Joan Miró, I think.

Sometimes, bases are simple ceramic plates, isolated or multiples: they are truly paintings, pictorial works (or drawings or monotypic engravings) in clay. At other times the base is rolled up and holds itself, or acquires other more complicated shapes. The naturalness (again that word) with which the artisans’ work melds with sculptural form and the pictorial surface is admirable. The “expressive integration”, so diligently sought after in other times by our muralists, here has a radical and unusual manifestation.

His recent exposition at the Museum of Modern Art, for example, demonstrates all the resources and talent of an artist in his prime. His best is there as always, but he saved new things for us: multiple piece reliefs or straightforward superimposed ones stretching along the walls and the floor, entwined chains and unusual progressions, the precise delicateness of a material that seems to envelope us in its arms, pieces that are enjoyed in different ways when looking at them from close up and far away, when touching them, and making them ours. And, the technique, as it should be, is always in the service of poetry.

We are in the presence of an “artisan” on the one hand, and on the other, one of our finest, most original and heartfelt painters and sculptors. There it is and you must see it.

Me ha ha sucedido gue al mencionar el nombre de Gustavo Pérez, la gente me pregunta quién es él. Y “la gente” puede ser, en ciertos casos, alguien a quien supondría enterado, quien debiera estarlo.

Se trata de algo absurdo: Gustavo Pérez es uno de nuestros mayores artistas. Varias cosas explican esta ignorancia, pero quizá la mayor es simplemente que Gustavo Pérez es ceramista. No culpemos enteramente al público: la cerámica es un territorio en que las fronteras entre “arte menor” y arte a secas son particularmente nebulosas, y Gustavo enfatiza siempre su condición de artesano; de artesano enorme, añado yo, de técnico sapiente e inventivo.

Fiel a esa vocación, gustoso de la manualidad de su obra, del trabajo en el torno, del virtuosismo en la elaboración de cacharros delgados cual papel, de la obsesiva minucia de sus ollas y platos y tazones, Pérez sigue produciendo magníficos objetos utilitarios, y creo que jamás dejará de hacerlos. Tengo la impresión de que esto es, para él, un imperativo moral —Gustavo es un hombre profundamente preocupado por las cuestiones éticas—, el darle el menudo esplendor en lo cotidiano.

Esplendor, sí, belleza; Gustavo ha descubierto cómo una línea incisa en la pared de arcilla puede abrirse al presionarla desde dentro, como un maravilloso sexo femenino. Sus vasijas surcadas, barbechadas en pautas de una diversidad interminable, su elegancia esencial, su indagación perpetua de las texturas y los esmaltes de alta temperatura, su condición de trabajador infatigable, inteligente y curioso, han dado lustres nuevos al menguado abolengo de este país de viejos ceramistas.

Casi a regañadientes, casi bajo protesta — ¡y felizmente, claro!—, Gustavo fue capaz de evitar todas esas virtudes y todos esos hallazgos fueron adquiriendo autonomía, y apareciendo en piezas en las que el puro crear con la materia es la razón de ser; aquí el arte más alto se adueña de la escena.

Entrar en el taller de Gustavo Pérez en su paraíso coatepecano, es como entrar en un laboratorio de la reflexión y el juego. Ordenados y limpios sobre altos estantes, reposan los “bocetos” de los que este artista sorprendente ha de extraer sus piezas acabadas. En ocasiones, los objetos no tienen más de tres o cuatro centímetros: la arcilla se comprime, se ahueca, se arrastra, se teje en intrincadas telarañas tridimencionales. Un pellizco en la arcilla puede dar resultados sorprendentes, si el que pellizca es Gustavo Pérez. El barro de estos objetos diminutos es como un polen que ya tiene la promesa de los árboles maduros.

Las esculturas cerámicas de Gustavo acatan con orgullo los dictados de su materia prima: sólo de lodo podrían estar formadas. La naturalidad de sus caídas, las barras que las forman, sus caras pulidas o granulosas, o enloquecida y ordenadamente cubiertas de entrantes y salientes, todo habla de un entendimiento y de un respeto absoluto del artista por sus medios de expresión. En ocasiones, una tradicional vasija torneada se rompe, se desfleca, se tuerce o se recompone, y esa metamorfosis le hace saltar de la alacena al museo, sin dejar de pertenecer a la alacena. Con estas piezas inútiles (o inutilizadas), Gustavo se convierte en un abanderado excepcional de la reciente escultura mexicana.

En muchas de sus piezas, Gustavo Pérez se deleita —con su paciencia de benedictino— cubriendo las superficies con preciosos, multicolores y complejos dibujos. Sorprende la firmeza de su trazo, el donaire, la delicadeza y la variedad. El barro se tapiza de escarificaciones, de líneas incisas y segmentadas en las que la policromía y el ritmo son fascinantes, y hay un regodeo con la geometría que se convierte en estrellas y constelaciones que parecen moverse, y un aire festivo con el que Paul Klee y Joan Miró estarían, creo, contentos.

Algunas veces, el soporte son simples placas de cerámica, aisladas o en polípticos: son pues verdaderamente cuadros, obras pictóricas (o dibujos, o grabados monotípicos) sobre barro. En otras ocasiones la placa se enrolla y auto transporta, o adquiere otros cuerpos más complejos. La naturalidad (de nuevo la palabra) con que se funden la obra artesanal con la forma escultórica y la superficie pictórica es admirable. La “integración plástica”, tan empeñosamente buscada en otros tiempos por nuestros muralistas, tiene aquí una manifestación radical e inusitada.

Su reciente exposición en el Museo de Arte Moderno muestra, por ejemplo, todos los recursos y todos los talentos de un artista en plenitud. Está allí lo mejor de siempre, pero nos reservaba cosas nuevas: relieves de piezas múltiples o de planos superpuestos que se extienden sobre los muros o el piso, cadenas entrelazadas y secuencias extrañas, la rigurosa morbidez de una materia que dan ganas de envolver con los brazos, piezas que se disfrutan de modos diferentes al mirarlas de lejos y de cerca, al tocarlas, al hacerlas nuestras. Y la técnica, como debe ser, siempre puesta al servicio de la poesía.

Estamos en presencia de un “obrero del arte” por un lado, y por otro, de uno de nuestros pintores y escultores más finos, más originales y más hondos. Allí está y hay que mirarlo.