Isamu Noguchi: On Becoming An Artist

Wendolyn Lozano Tova

Download Complete PDF / Descargar

Interview with Amy Wolf, Curator

The Great Depression took Noguchi to Mexico. Could you talk about Noguchi’s friendship with Frida Kahlo?

Amy Wolf: Noguchi initiated a friendship with Frida Kahlo in 1936, during his stay in Mexico City, where he went in order to complete a mural at the Mercado Abelardo Rodriguez under the supervision of Diego Rivera. While the love affair between Kahlo and Noguchi was short-lived, their friendship endured, as evidenced by his enthusiastic support of her exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in 1938 and his visits to her during her various hospital treatments in New York during the 1940s. Noguchi admired Kahlo’s artwork and especially appreciated her zest for life despite her chronic debilitating medical problems.

The exhibition is titled On Becoming an Artist: Isamu Noguchi and His Contemporaries, 1922–1960. Yet the artist also lived for 13 years in Japan. Do you think these years influenced the artist in such a way that he uses simple forms and shapes? It seems that he feels inclined to integrate art into his daily life.

Amy Wolf: Noguchi’s Japan experience was indeed very important to many aspects of his career, including his use of materials, philosophical outlook, and approach to gardens and other social spaces. However, this exhibition focuses on a network of artists centered mostly in the U.S. and Europe.

After an exhibition by Brancusi organized by Duchamp in 1926 at Brummer’s Gallery, Noguchi traveled to Paris (thanks to a Guggenheim grant). After a few months, the poet Robert McAlmon became Brancusi’s assistant. How did this encounter influence Noguchi?

Amy Wolf: According to Noguchi’s reminiscences, Robert McAlmon served as a useful conduit through which the young sculptor met the master Brancusi. While the details of the encounter are not completely known, it is believed that McAlmon met Noguchi shortly after his arrival and introduced Brancusi to him. Brancusi was a lifelong influence on the work of Noguchi in multiple ways, including his example of sculptural technique, use and care of tools, and the philosophical underpinnings of the work. He provided a break from an academic approach, and also a connection to the ancients and the eternal. Noguchi remained in contact with Brancusi until the older artist’s death.

Amy Wolf: According to Noguchi’s reminiscences, Robert McAlmon served as a useful conduit through which the young sculptor met the master Brancusi. While the details of the encounter are not completely known, it is believed that McAlmon met Noguchi shortly after his arrival and introduced Brancusi to him. Brancusi was a lifelong influence on the work of Noguchi in multiple ways, including his example of sculptural technique, use and care of tools, and the philosophical underpinnings of the work. He provided a break from an academic approach, and also a connection to the ancients and the eternal. Noguchi remained in contact with Brancusi until the older artist’s death.

When Noguchi lived in Paris, the cultural scene was vibrant. During a time dominated by Surrealism, how did Giacometti influence Noguchi’s work? What other artists influenced his work as well?

Amy Wolf: Many artists influenced Noguchi’s work. Earliest in his career were those artists who could provide instruction in sculptural technique: Gutzon Borglum, Onorio Ruotolo, Ahron Ben Shmuel, and Constantin Brancusi were especially important. In Paris in the 1920s, more mature American artists, such as Stuart Davis and Morris Kantor, provided an example of artists who were secure in their methods, with gallery representation and some critical appreciation. At the same time, younger artists provided friendship, support, and introductions to other opportunities. These included people like Alexander Calder, Andrée Ruellan, and Marion Greenwood. In the 1930s, Noguchi’s close friendships with Arshile Gorky and other artists with studios in New York City’s Union Square neighborhood provided a network of young struggling artists seeking to respond to growing European Fascism and the Depression. Noguchi actually gained firsthand knowledge of Surrealism in New York, where many of the Surrealists had come to live during wartime. Many of the European Surrealists showed in the New York galleries frequented by Noguchi and his friends, and he exhibited with many of these same artists in the chess show at the Julien Levy Gallery in 1946.

Are Noguchi’s biomorphic forms related to Fuller’s view in the sense that Nature has to be seen through Nature’s eyes?

Amy Wolf: Noguchi and Fuller maintained a lifelong friendship. Fuller’s utopian ideas about society and the role of technology and design in improving life were especially appealing to Noguchi, who often assisted Fuller in rendering his designs, especially in the 1930s–for example for Fuller’s Dymaxion car. Noguchi and Fuller also shared an interest in flight and industrial materials that is evidenced in various periods of Noguchi’s work, including his experiments with chrome in the portrait of Fuller, stainless steel in the Associated Press wall plaque, and aluminum in the 1950s sculptures. As far as Noguchi’s biomorphic forms, I believe that they are less the result of ideas shared with Fuller, than they are related to Surrealism, and perhaps early work by artists who would become known as Abstract Expressionists.

The exhibition analyzes the crisis that took place in the 30’s. However, it also talks about WWII. You can only find one piece related to it, though: This Tortured Earth (1940). Don’t you find it a bit strange that Noguchi decided to work for Knoll & Herman Miller? What made him work for them under these circumstances?

Amy Wolf: There are other works in the exhibition that are related to Noguchi’s specifi c experience of World War II, including My Arizona, which responds to his experience at the Japanese internment camp at Poston Arizona, and My Pacific, which utilizes driftwood, a material used at Poston. Noguchi’s mural in Mexico City specifically addresses the threats of Fascism and Nazism, which led to WWII.

As for Noguchi’s decision to work for Knoll and Herman Miller, this was an extension of ideas about utility that he had been considering as early as the 1930s. While he did not develop his first commercial product until the Zenith Nurse intercom in 1937, Noguchi–unlike many of his artist colleagues–believed that an object’s usefulness provided an added benefit. He did not see the term “designer” as a pejorative description. At Knoll and Herman Miller he joined many other talented individuals to create well-designed and beautiful furniture and objects that could be enjoyed by a more mass audience.

How did Nouguchi end up collaborating with Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham, John Cage, and George Balanchine? How did Noguchi get into theater & ballet?

Amy Wolf: Noguchi’s first experience with theater occurred in 1926, with his design for Michio Ito, a Japanese modern dancer and choreographer who was an acquaintance of Noguchi’s father. Ito proved very helpful to the young Noguchi assisting him in finding portrait commissions and making introductions in Europe and later in California.

Many roads led to Martha Graham, including the dance activities of Noguchi’s younger sister Ailes, the shared location of the Graham and Noguchi studios, and a network of shared friends. As Merce Cunningham was an early Martha Graham dancer (as were later Noguchi collaborators Erick Hawkins and Yuriko), he and John Cage probably met Noguchi through Graham. Balanchine probably became acquainted with Noguchi both through his work with Graham and through Noguchi’s earlier intersection with Balanchine’s collaborator Lincoln Kirstein, which took place in 1930, when Noguchi exhibited with Kirstein’s Harvard Society of Contemporary Art.

Does this exhibit show photographs, drawings, diaries and personal objects that show Noguchi’s relationships with his friends? What is the most important or interesting of them all?

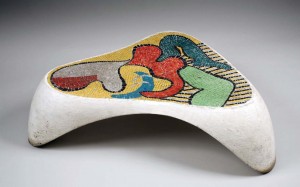

Amy Wolf: The exhibition includes many photographs, drawings, letters, and documents related to his friendships. There are many interesting ones, but it was especially rewarding to locate the actual table that Noguchi and mosaic-artist Jeanne Reynal created in collaboration. Although the table was depicted in a small drawing in a letter from Reynal to Noguchi that is in the Noguchi archive, its whereabouts were previously unknown.

Posted: April 24, 2012 at 9:10 pm

Woah this is magnificent i like studying your articles. Stay up the good work! You know, lots of people are looking round for this info, you can help them greatly.