Spending the Night With Apichatpong Weerasethakul

So Mayer

Last month I spent the night with filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul.

It wasn’t just me: more than a hundred people gathered on the brand-new plush purple seats of Tate Modern’s Starr Auditorium for the world-first Weerasethakul all-nighter screening every short and music video he has ever made, along with many of his features. If you’ve ever seen a Weerasethakul film–maybe Tropical Malady, with its psychic tiger; or Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, the first film featuring an animatronic catfish and monkey ghosts to win the Palme d’Or–the idea of spending all night in a hypnagogic state with dozens of total strangers will make perfect sense.

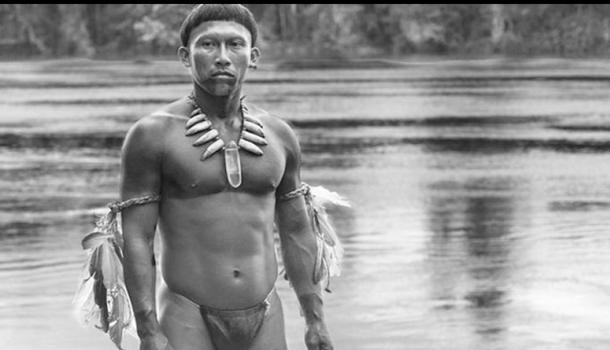

If you haven’t, then his latest film Cemetery of Splendour (Rak Ti Khon Kaen) is a great place to start. It had a limited release in the USA this March, and is still travelling to festivals. When I saw it at the London Film Festival, the director introduced it by saying it didn’t matter if we fell asleep during the film; in fact, he’d made it to create that effect. Unless you’re completely immune to kinaesthesia, you will nod off, because the film is about a group of soldiers with sleeping sickness and a volunteer, Jenjira, who looks after them as they undergo a new therapeutic treatment, being bathed in soft neon light.

Jenjira succumbs to sleep herself at a certain point, after she goes on a date with Itt, an awakened soldier who passes out during the horror film they go and see. They dream together (although Itt appears in the body of Keng, the female medium who is trying to communicate with the soldiers, and may also be the ancient Laotian princess who has lunch with Jenjira earlier in the film), walking through the ancient temple whose ruins lie under the clinic where the soldiers are sleeping. A strong but subtle current of political critique runs through the film: anti-military, anti-royalist, queer and feminist, against forgetting. And the film’s delicacy of tone, its elegance of imagination and its curiosity about imaginative states are so consistent and persistent that no matter when (forget whether) you fall asleep, once you awaken, you are immediately immersed in Weerasethakul’s world again.

Part of this is the incredible ability of his cinema to follow the illogic of dreams and reflection, the strange patterns of associations that seem so right when you’re asleep and so laughable when you try to explain them on waking. It slowly emerged, over the course of the night into the dawn, that something else was going on as well; another hold on my attention. On the surface, it’s an element that seems obvious: the continuity of Weerasethakul’s worldview, which ensures all his films resonate with each other.

Many of them are set and shot in Khon Kaen, the region where he grew up as the son of two doctors–and many of his films feature hospitals or medical procedures, from the strange skin cream of Blissfully Yours to the tender kidney drainage in Uncle Boonmee, via the singing dentist of Syndromes and a Century. He casts the same actors–such as Jenjira Pongpas Widner, Banlop Lomnoi, and Sakda Kaewbuadee–across many of his films, and frequently creates characters called Keng and Tong.

These are not interlinked stories, unlike the work of Wong Kar-wai, where minor (and even major) characters reappear from film to film across decades. Weerasethakul’s characters reincarnate rather than recur, sometimes changing genders or historical eras. Sometimes the actors are cast as versions of themselves, like Pongpas Widner in Cemetery. Familiar elements are rearranged, so that each film feels like a dream of the films that came before it. Weerasethakul often works by making shorts and installations that build toward a finished feature, as with the Primitive installation that prefigured Uncle Boonmee, introducing the locale, the context and the ideas–which does help the viewer grasp the filmmaker’s unique mixture of Buddhism, Thai B-movies, American avant-garde film and video, and contemporary politics. Perhaps his restless repetition comes from his love of soap operas, as evidenced in Haunted Houses, an early 60-minute film that recruits an entire village to act out two episodes of a popular soap, recasting each character from scene to scene.

There is something of the serial to Weerasethakul’s films: not narratively, but in their mood and relation to place. Something similar is at work across several of Hirokazu Koreeda’s films, which feel like they take place in the same small town, or among related families – as if the abandoned children in Nobody Knows grew up to become the three sisters whose mother left them after her husband remarried in his most recent film, Our Little Sister. There’s no checklist of clever interconnections or inside jokes, just a sense of witnessing a singular imagination working itself out on screen.

Sheila O’Malley writes, “The film works the way a Shakespearean sonnet works in that it actually increases its impact the moment it’s over.” This is true, as I discovered in that tender (and freezing cold) early morning by the gray Thames river, which is nothing and everything like Weerasethakul’s Mekong, not just from Cemetery, but from his career as a whole. And yet, just as there is brilliance and delight in every line of a Shakespearean sonnet, just as–like the jewellery placed among plants in his short, My Mother’s Garden–every Apichatpong Weerasethakul film dazzles as it catches the light. What an experience to wake up to.

![]() Sophie Mayer is a regular contributor to Sight & Sound and The F-Word.She’s the author of Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema and The Cinema of Sally Potter: A Politics of Love, and the co-editor of Catechism: Poems For Pussy Riot, The Personal Is Political: Feminism andDocumentary and There She Goes: Feminist Filmmaking and Beyond. Her Twitter is @tr0ublemayer

Sophie Mayer is a regular contributor to Sight & Sound and The F-Word.She’s the author of Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema and The Cinema of Sally Potter: A Politics of Love, and the co-editor of Catechism: Poems For Pussy Riot, The Personal Is Political: Feminism andDocumentary and There She Goes: Feminist Filmmaking and Beyond. Her Twitter is @tr0ublemayer

Posted: May 26, 2016 at 10:50 pm