Gabriel de la Mora: Universality of the Form

La forma

Carmen Cebreros

GABRIEL DE LA MORA. THE PLEASURE OF VISUAL PERCEPTION

[Translated by Debra D. Andrist]

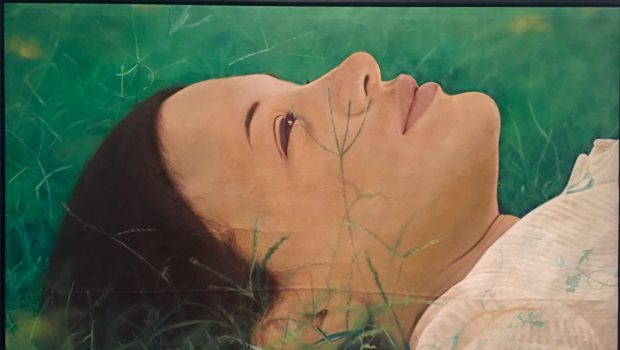

Restless and prolific, Gabriel de la Mora (1968) has explored a broad expanse of mediums and props throughout his artistic career. He has moved through drawing, painting, sculpture, and video-documented performances, going back and forth among these constantly, even though–as he himself declares–he doesn’t start a work until having finished the previous one, no matter how much time it requires. A deep interest in portraiture underlies this discipline, but it’s mainly due to the paradoxes of representation and the tensions between an image, the visual referents associated with it, the material of which it is formed and its implied energy. An energy that renounces any possibility of being molded but at the same time exists, controlling and affecting all artistic actions.

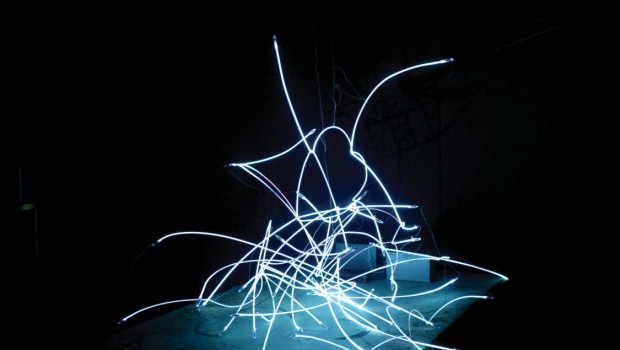

De la Mora’s best-known work is his series of drawings, in which family members and persons who form part of his emotional circle appear in specific contexts or episodes. These subjects are, in a way, donors of the element with which the manual sketch on the paper is replaced: hair. These drawings, based on lines, are made under a meticulous and quasi-surgical procedure of measurement, cutting and managing the material so as to take on the shapes that compose the image. The hair functions visually as a line. Nonetheless, there is an invisible coming-to-terms by means of which the threedimensional nature of the element is transferred to the mounted plane. Said coming-to-terms in the account of the work has unchained a series of reflections in this artist with regards to the boundaries between drawing and sculpture. In pieces like Parallel Blind Lines (2008), the artist uses the most traditional definitions of these genres as a program from which to activate the fluctuations between one and the other. If a line is a succession of points on a plane, each hair is a point from the imaginary transverse view and the plane is a homogenous surface of 28 x 21.5 cm (the measurements of a regular letter-size page). But this surface is constructed, sheet to sheet, in the manner of an interwoven frame. As on a loom, two hairs are inserted (one paper to every six) in equidistant rows forming two parallel lines that are viewed laterally, scattered outwards in various directions: half thicket–half calligraphy. This whimsical arrangement, seesawingly shaped by the tubular capillary structure, is analyzed in works like Circles III (2008), in which De la Mora leaves the linkages between the hairs detached, thereby showing the natural tendency of the medium to form perfect circles as in 412p, which is a network of hairs threaded on the paper and knotted, generating both a barely-perceptible relief and a drawing of shadows over a white surface. In Structure (2008), this same type of random filaments is raised to a greater scale using a material that demolishes subtleties– neon tubes, converted into an incandescent scrawl in which the homogeneity of the material and the complexity of the constructed forms are contrasted.

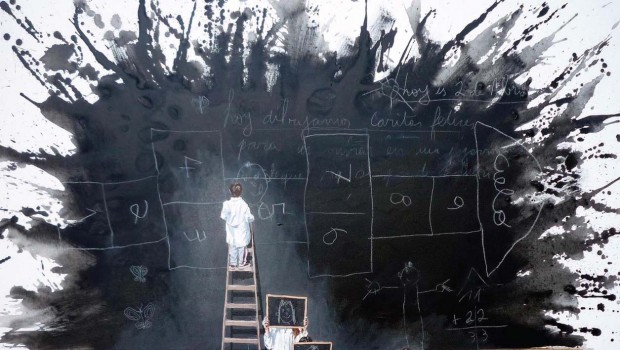

Score (2006) is a poetic piece in which a page becomes musical staff-ruled paper designed for a potential melody in development, while at the same time discontinued straight lines–also made with human hair, partially attached to the mounted base–generate their own rhythm and movement, alluding to a composition that overflows the grid and predetermined pattern. This space and expectation regarding randomness materializes in the series Burned Paper (intiated in 2007 and continuing on to the present) in which De la Mora investigates the transformation of a mounted plane (a sheet of rag paper) into a volume modeled exclusively by the effect of fire. To make the material char and tinge with black in a homogenous manner is a completely unpredictable undertaking; at the very least it is not something that De la Mora intends to control through a determined system. In contrast, he hopes to be able to fail a thousand times, to burn and to disintegrate a thousand pages before making sure the volume is preserved and doesn’t fall apart.

The marks, seen as signs, code and fragment of material, in which all the information that makes up an individual is invisibly contained, is a theme that obsesses De la Mora. Repeatedly, his typing-like tracks–an ensemble of lines again, but also an allegory of the sense of touch–are the motive to represent, by way of exercises of absolute meticulousness, an ironic gesture in which the artist submits himself to a conscientious self-observation that is reminiscent of the popular phrase that pronounces that something is as well-known as the palm of one’s hand.

The series of paintings, GMC O+ / 14,565.6 Square Centimeters (2009) are composed of 28 masonite panels, illustrated and bearing incisions, which are reminiscent of the slit canvases by Italian artist Lucio Fontana. The pictorial medium in this case is the artist’s own blood, which is applied coat by coat–in the tempura manner, a technique utilized in medieval painting–until the desired tonalities are achieved. The color of these surfaces is very similar to the pigmentation of the skin, and the channels drawn on each panel resemble injuries without scars, acting also as receptacles of the corporeal fluid.

In an inverse and deconstructive process, the artist dematerializes a text and materializes it as a secret cipher in a miniscule cube of rubber residues, located on a sheet stained with melted graphite: a piece about which the artist tells us only that “the information of ideas, concepts and all the things that I have done and never have said to anyone about myself, is contained in said paper, that I wrote over five hours, read and erased immediately, leaving a blank paper with the records of the action.” Thus, De la Mora produces a metaphor about the impossibility of communication–or the desire to be silent–an self-refl exive process that is transfi gured by clear references to the history of art: Erased De Kooning Drawing (1953) in which Robert Rauschenberg disappears a drawing-on-paper made by De Kooning, establishing himself as author in the presence of such elimination of the image; from another standpoint, the iconic cube, a prominent solid proffered on repeated occasions by the Minimalists in the late Sixties, in their zeal for the dissolution of subjective manifestations through the universality of form.

Among the series of works in which Gabriel De la Mora employs alphabet soup as primary material, Self Portrait with Alphabet Soup II (2001) stands out, a kind of parody of self-representation and illegibility. A series of letters made out of dough, also painted in white, form a human silhouette suspended transversely over a blank canvas. These letters form an illegible phrase if the work is seen from the front. De la Mora has authenticated this work by making use of lateral lighting, which makes the letters project a shadow over the surface of the canvas, but in an inverted sense (it bears mentioning that this is his natural form of writing, “ina-mirror,” because the artist is both dyslexic and lefthanded), whose partially-understandable text makes reference specifically to the mode of writing in relation to the artistic vocation. The humor of this work evokes the word games of Bruce Nauman, for example, in his work Eating My Words (1966-67), in which the artist appears seated at the table with a plate in which something similar to pancakes smeared with a marmalade is served: this food takes the form of the letters O-R-D-S . . . the W seems to have been savored right at the moment the photograph was taken.

De la Mora is convinced of the force deposited upon constructing an object and the charge that remains contained within. This artist doesn’t capitulate to the voracity of our time, which demands from all spheres of human action–including the art sphere–a rationale of expedited and efficient production. His work vindicates the power of contact, time, and care. His pieces astonish us with their fragility and delicacy, but at the same time they reflect a labor of observation, analysis, and conviction that makes us as spectators inevitably stop for a moment to recognize the pleasure of visual perception.

GABRIEL DE LA MORA. EL GOZO DE LA MIRADA

Download Complete PDF / Descargar

Inquieto y prolífico, Gabriel de la Mora (1968) ha explorado un extenso abanico de medios y soportes a lo largo de su carrera artística. Ha transitado por el dibujo, la pintura, la escultura, las acciones documentadas en video; yendo y regresando entre ellos constantemente, aunque –según él mismo declara– sin comenzar una obra dejando inconclusa la anterior, independientemente del tiempo que cada una requiera. A esta disciplina subyace un profundo interés por el retrato, pero especialmente por las paradojas de la representación y las tensiones entre una imagen, los referentes visuales a ella asociados, la materia de que está conformada y la carga energética implicada, misma que renuncia a cualquier posibilidad de plasmación, pero que igualmente existe, opera y afecta todo acto artístico.

El trabajo más reconocido de De la Mora es su serie de dibujos en los que aparecen familiares y personas que forman parte de su campo afectivo en contextos o episodios específicos. Estos sujetos son, a su vez, donadores del elemento con que los trazos manuales sobre el papel son reemplazados: el cabello. Estos dibujos a base de líneas están hechos bajo un minucioso y cuasi quirúrgico procedimiento de medición, recorte y manejo del material para que adopte las formas que componen la imagen. El cabello funciona visualmente como una línea; sin embargo, hay una negociación no visible de por medio que traslada la naturaleza tridimensional del elemento al soporte plano. Dicha negociación en la factura de la obra ha desencadenado una serie de reflexiones en este artista respecto de los lindes entre el dibujo y la escultura. En piezas como Parallel blind lines (2008) toma las defi niciones más tradicionales de estos géneros como programa desde el cual activar las fl uctuaciones entre uno y otro: si una línea es una sucesión de puntos en un plano, cada cabello es un punto desde una vista transversal imaginaria y el plano es una superficie homogénea de 28 x 21.5 cm (medidas de una hoja tamaño carta común). Pero esta superfi cie está construida pliego a pliego a la manera de un encuadernado, en cuyos intersticios (una hoja sí y una no) se insertan –como en un telar– dos cabellos en filas equidistantes formando dos líneas paralelas, que vistas lateralmente se distribuyen hacia varias direcciones: mitad maleza, mitad caligrafía. Esta caprichosa disposición determinada aleatoriamente por la estructura capilar es analizada en obras como Círculos III (2008), en la que De la Mora deja sueltos los enlaces entre cabellos, mostrando así la tendencia natural del medio para formar círculos perfectos, así como en Boceto 4642, que es una red de cabellos (4642 enumerados sistemáticamente de acuerdo con el orden en que fueron añadidos) ensartados en el papel y anudados, generando un relieve apenas perceptible y, al mismo tiempo, un dibujo de sombras sobre la blanca superficie. En Estructura (2008), este mismo tipo de filamentos azarosos es llevado a una escala mayor en un material que abate las sutilezas –tubos de neón que se convierten en un garabateo incandescente, en el que contrastan la homogeneidad del material y la complejidad de las formas construidas.

Partitura (2006) es una poética pieza en la que una página se convierte en papel pautado dispuesto para una potencial melodía por desarrollar, al tiempo que las discontinuidades de las líneas rectas –hechas también con cabello humano parcialmente adherido al soporte– generan su propio ritmo y movimiento, aludiendo a una composición que se desborda de las retículas y del patrón predeterminado. Este espacio y expectativa sobre el azar se materializa en la serie de Papel quemado (iniciada en el 2007 y que continúa hasta la fecha) en la que De la Mora investiga la transformación de un soporte plano (una hoja de papel de algodón) en un volumen, modelado exclusivamente por el efecto del fuego. Lograr que el material se carbonice y tiña de negro de manera homogénea es una empresa completamente impredecible, al menos no es algo que De la Mora intente controlar bajo un sistema determinado; él, en cambio, espera, pudiendo fracasar hasta mil veces, quemar y desintegrar mil páginas, antes de conseguir que el volumen se preserve y no se fragmente.

Las huellas, en tanto signo, código y fragmento material, en que está invisiblemente contenida toda la información que compone a un individuo, es un tema que obsesiona a De la Mora. Repetidamente sus huellas dactilares –un conjunto de líneas nuevamente, pero también una alegoría del tacto– son el motivo a representar, a través de ejercicios de absoluta minuciosidad: irónico gesto en que el artista se somete a una concienzuda auto-observación, que recuerda la popular frase que dicta que algo es tan conocido como la propia palma de la mano.

La serie de pinturas GMC O+ / 14,565.6 centímetros cuadrados (2009) está compuesta de veintiocho paneles de masonite, esgrafiados y con incisiones que recuerdan los lienzos rajados del italiano Lucio Fontana. El medio pictórico, en este caso, es la sangre del propio artista, que es aplicada veladura tras veladura –a la manera del temple, técnica utilizada en la pintura medieval– hasta obtener las tonalidades deseadas. El color de estas superficies es muy similar a la pigmentación de la piel, y los canales dibujados en cada tabla asemejan heridas sin cicatrizar, mientras que son también receptáculos del fluido corporal.

En un proceso inverso y deconstructivo, el artista desmaterializa un texto y lo materializa como secreto cifrado en un minúsculo cubo de residuos de goma, colocado sobre una hoja manchada de grafito desvanecido: pieza sobre la que el artista sólo nos deja saber que en dicho papel estuvo contenida “la información de ideas, conceptos y todas las cosas que he hecho y nunca le he dicho a nadie sobre mí; que durante cinco horas escribí, leí y borré inmediatamente, dejando un papel en blanco con los registros de la acción”. De la Mora produce así una metáfora sobre la imposibilidad de comunicar –o el deseo de callar– un proceso autorefl exivo que se transfi gura en claras referencias de la historia del arte: Erased De Kooning Drawing (1953) en donde Robert Rauschenberg desaparece un dibujo sobre papel hecho por De Kooning, instaurándose como autor ante tal eliminación de la imagen; por otro lado, el icónico cubo, prominente sólido presentado en repetidas ocasiones por los minimalistas de finales de los años sesenta, en su afán por la disolución de las manifestaciones subjetivas en la universalidad de la forma.

Entre la serie de trabajos donde Gabriel de la Mora emplea la sopa de letras como materia prima, destaca Autoretrato con sopa de letras II (2001) que es una especie de parodia sobre la auto-representación y la ilegibilidad. Sobre un lienzo blanco están suspendidas transversalmente una serie de letras de pasta pintadas también en blanco formando una silueta humana; estas letras conforman una frase ilegible si el cuadro es visto de frente. De la Mora ha documentado esta obra, valiéndose de una luz lateral que hace que las letras proyecten una sombra sobre la superfi cie del lienzo, pero en un sentido invertido (valga mencionar que ésta es su forma natural de escritura, “en espejo”, pues este artista es disléxico y zurdo), cuyo texto parcialmente comprensible hace referencia justamente al modo de escribir en relación con la vocación artística . El humor de esta obra evoca los juegos de palabras de Bruce Nauman, por ejemplo en su obra Eating My Words (1966-67) o donde el artista aparece sentado a la mesa con un plato en que está servido algo parecido a unos hot-cakes a los que unta mermelada; este alimento tiene la forma de las letras O-R-D-S… la W parece haber sido degustada para el momento en que fue tomada la fotografía.

De la Mora está convencido de la fuerza que se deposita al construir un objeto y la carga que queda contenida en él; este artista no claudica ante la voracidad de nuestro tiempo que demanda de toda esfera de acción humana –incluida la esfera del arte– una lógica de producción expedita y eficiente. Su trabajo reivindica el poder del contacto, el tiempo y el cuidado, y sus piezas nos asombran por su fragilidad y delicadeza, pero al mismo tiempo porque reflejan una labor de observación, análisis y convicción que, a nosotros espectadores, nos hace detenernos e inevitablemente reconocer el gozo de la mirada.