The Sky is the Limit: A Conversation with John Henry

Ebony Porter

Download Complete PDF / Descargar

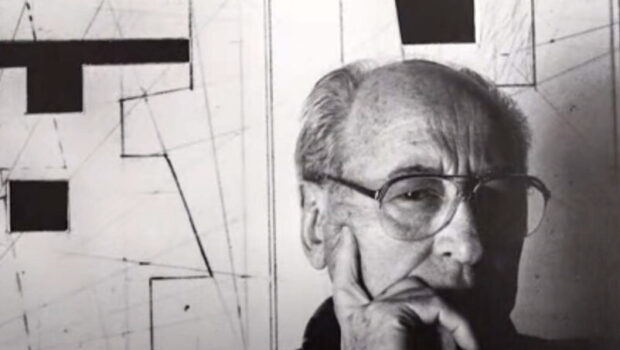

Poised to build the tallest standing sculpture in the United States with the exception of the Gateway Arch in St.Louis, the American sculptor John Henry continues to push sculptural limits as he has done throughout his 45 year long career. In Houston for his solo exhibition and book-signing event at Sonja Roesch Gallery celebrating John Henry, a 517-page book released earlier this year by Ruder Finn Press, I sat down with the artist to talk about the evolution of his work and the approaching uber-monumental project mentioned above. Experimenting with new technology and the challenges of reaching new heights, I found the artist to be as down to Earth as the materials he works with.

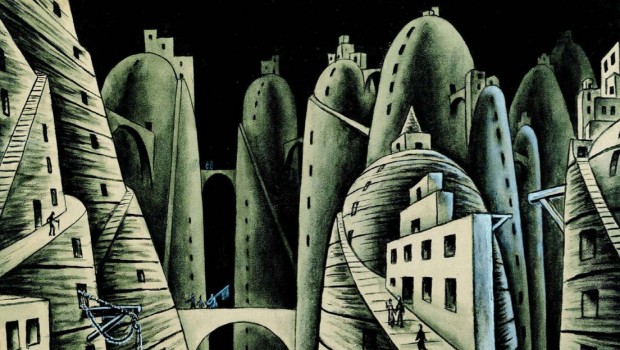

Henry is known primarily for his largescale sculptures with roots in Constructivism and the modern design of Bauhaus. With such references to art movements and schools of thought that stretch back to almost 100 years ago, it’s safe to say that Henry’s work is timeless. Included in numerous private, public and museum collections, his work has transformed cityscapes and landscapes across the world.

“If you stay longer than 3 days in Houston, you’re subject to get arrested,” the artist told me, and while I didn’t press him on that comment, I imagine his experiences in Houston must be chock full of revelry. His history with Houston stretches back to 1975 with the invitational exhibition Monumental Sculpture which included big names like Donald Judd, Clement Meadmore and James Surls. According to the artist it was “the fi rst large scale sculpture exhibition in this part of the country.” 1975 also marked the beginning of a three year winter residency in Houston at Pin Oak Stables, where he built the sprawling work Pin Oak, which is now in the collection of the Bradley Sculpture Garden in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. His first solo exhibition in Houston was at Greenway Plaza in 1976 and the timeline continues in early 2011 with STRUCTURES at Appropriate Scale at Sonja Roesch Gallery.

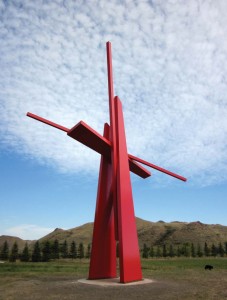

His sculptures are commanding, and some of the more recent works seem to reach for the Heavens. While some reside perfectly amid the hard linear faces of urban spaces, others stand in silence surrounded by nothing but the sky and earth. They are the only geometric forms in these natural surroundings and electrify the pastoral landscape. Imagining one of his monumental works in the center of the desolate Australian outback, I asked if there’s a place anywhere in the world where he would want to see one of his sculptures installed.

“You know I have to really confess I’ve never thought of that. You’ll go somewhere and think boy, a piece will look good there. But having a place that you covet for a site, no. I’ve put pieces in nature. For example one of the last photographs we put in the book is of a piece (titled River High) that went in northern Wyoming with the Big Horn Mountains in the background. It’s not like it’s barren earth, but it’s large expanses of space. I’ve done that a few times. The piece in Wyoming, there’s nothing between there and the mountains. And the woman I did it for said “I hope nobody builds a barn over there you know.”

Unparticular to the challenges of an urban or natural space to work with, Henry isn’t a fan of the terminology “site-specific.” Critics, he explains, focus too much on the idea of a sculpture being or not being site-specific. “What they’ve never connected with is that sites change, such as the development and expansion of cities. When you make sculpture,” Henry says, “don’t get too hung up on the site specific stuff, because you may build a piece that won’t fit anywhere.”

Over the years Henry’s work has shifted from horizontally weighted sculptures that reveal the nuts and bolts of its construction, to more recent works that stretch to heights of 80 feet and upwards, and maintain a sense of mystery in hiding the grit of its construction. This latest book chronicles the career of the artist beautifully in photographs, from his first commission in marble to his experiments in Land art to his most recent monumental sculptures built with steel.

An early example of his work is a sculpture that no longer exists from 1968 titled Peace. It appears to somewhat travel through the Earth. “That was built in a time when no one was selling large scale sculpture. You could count on less than one hand the artists that were successful selling anything over 20 feet. One was Alexander Calder. It just wasn’t happening. I was a student when I built that piece. It was a groundbreaking piece because people had not yet made sections of sculpture that were separated by large spaces but were still considered one piece. So nobody had done that at that time, that I know of.”

The transformation, change and challenges in his work is evident even in the small selection of sculptures at Sonja Roesch Gallery. Works on view range in date from Spirit of Miami, 1976 to the giant Red Sails, 2010 that looms in front of the gallery. We see those nuts and bolts disappear and taller works sit effortlessly poised and clean. What influenced the artist to shift toward building works that reached higher and higher?

The transformation, change and challenges in his work is evident even in the small selection of sculptures at Sonja Roesch Gallery. Works on view range in date from Spirit of Miami, 1976 to the giant Red Sails, 2010 that looms in front of the gallery. We see those nuts and bolts disappear and taller works sit effortlessly poised and clean. What influenced the artist to shift toward building works that reached higher and higher?

“I think the decision to go taller was probably influenced by available spaces for sculpture. There’s probably a little bit of economic influence there to try and utilize the urban space in such a way that it wouldn’t completely dominate the space to the point where people would say no, we don’t want it.”

His decision to eliminate the connectors, a trademark in his earlier work was based on the fact that the eye was interrupted by those “little dots” and took some of the mystery out of the pieces. “It was important at the time to articulate how the pieces go together, what makes them work, that was all very important. Now it’s not so much.”

Moving to present day, Henry is in the development stages of building a sculpture in Baltimore that will stretch to almost 300 feet high. This will be the tallest standing sculpture in the United States. The project was initially conceived for the 2010 World Equestrian Events in Lexington, Kentucky, also the artist’s birthplace. But funding and other circumstances curbed the project. A developer in Baltimore cottoned onto Henry’s proposal and history is about to be made. I wonder if this is his dream and how high the artist wants to go. “I would love to build a piece half to three quarters of a mile high. I’d love to do that. I’ve been working on some ideas.”

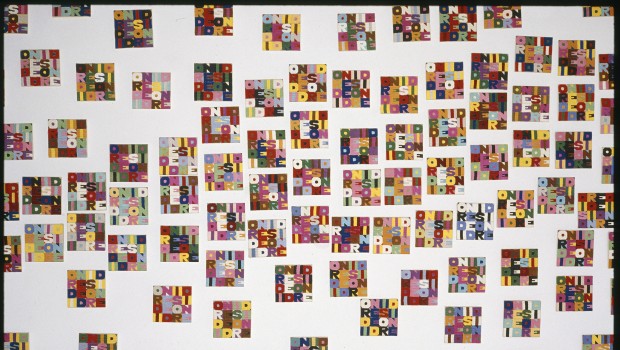

The sculpture, which is presently untitled, will light up. He is working with Danny Barnice who was involved in developing the well-received Jaume Plensa Crown Fountain sculpture in Chicago, the two large-scale faces that stand parallel to each other in LED lighting. “This LED light is something very interesting to me. What we’re doing is turning the surface of the sculpture into a TV screen. Every 1 3/8 inch is an LED pixel, tied directly into the computer.” Will it change color? “I can change anything. I can put your face on it. We are going to do a lot of different stuff. Pretty much the sky is the limit. I’ve done a lot of different stuff in the past, but it’s not what I’m known for.”

He is on the cusp of changing the landscape in Baltimore, but does he think artists truly change the world? “I do. I know they change communities, I know they change cities because I’ve been a part of it. That’s our job. To experiment, to try new things, try to put a different twist on things, try to educate people visually. And that’s what it’s all about. It’s a bonus when you get to learn too.”

“I know this; our particular world that we live in, that none of us are going to get out of alive, better darn well have some artist influence.” Full steam ahead with the sky as his limit, John Henry shows no signs of slowing down.

Posted: April 25, 2012 at 9:54 pm