And Yet It Moves!

¡Y sin embargo se mueve!

Domitille d'Orgeval

Translated from the French by Simon Hewitt

Elias Crespin belongs to the Kinetic Art movement of Latin America and has established an international name for himself through the ingenious beauty of his electrokinetic mobiles. His exhibition at Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino showcases an ensemble of works produced between 2010 and 2020, illustrating the various stages of his artistic evolution.

Crespin’s mobiles, based on repeated geometric elements like squares, circles, dots and lines, unfurl in space in rhythmic sequences that respond to mathematical algorithms. The programming is sophisticated and extremely precise and constitutes the culmination of years of research since Crespin’s days as an engineer at the turn of the millennium. After graduating from the Universidad Central de Venezuela in Caracas, he worked on conceiving specialist software programs before applying his knowledge to the field of art. The family context he grew up in also played a role in this change of career: his grandmother was the artist Gego (1912-94), renowned for her works in metal mesh. In Caracas–where he lived until moving to Paris in 2008–Elias Crespin got to know such giants of Kinetic Art as Otero and Soto, whose virtual cubes he decided to set into movement.

Crespin’s mobiles, suspended in the air by invisible threads, are imbued with a rhythm like that of breathing. They reveal themselves to the viewer little by little, without any mechanical linearity but with a variety of surprising effects. The ultra-minimalist Linea Copper (2016) is a linear structure that seems affected by a phenomenon of infinite articulation and dislocation. The dematerialized Tetralineados Transparente (2010) catch the eye through their projected shadows. The gently ascending and descending movement of Circuconcéntricos Alu Rouge-50 (2018) evokes a living world; the viewer is hypnotized by its soothing concentric construction.

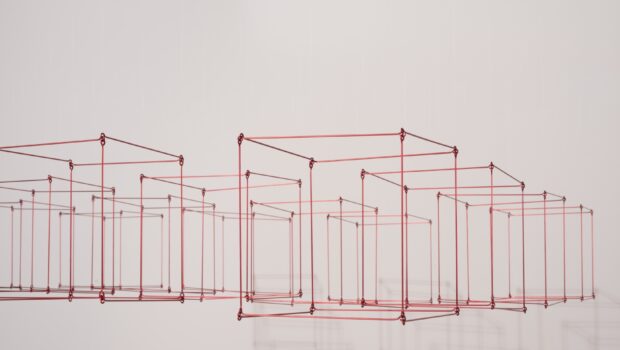

In La Danza de las Catenarias (2019), Crespin explores a world of curves and woollen thread, whose fluid and vibrant aesthetics starkly contrast with the angular mechanics of 12 Cubos en Línea Bleu (2020). The latter’s volumetric configuration creates long, orderly perspectives that give rise to complex geometric structures which, when they break up, defy description. The regular grid mesh of 4Net Inox Quadra (2013) seems to be blown invisibly from convex to concave, threatening to burst apart at any second. These unpredictable metamorphoses bear witness to Crespin’s endless imagination, underlined by his subtle handling of the aesthetic qualities of his materials: the transparent or colored luminosity of Plexiglas; the graphic finesse of metal; the contrast between gleaming metal and the matt nature of wool; the impact of colors on a work’s definition…

The mechanics governing his mobiles remain invisible, with their spatial configuration emerging little by little–drawn out over time, not speeded up. Crespin’s programmatic art favors slowness over speed: these works need to be observed at leisure. They create an impression of slowing down, even of time being suspended, that lets the viewer’s imagination run riot. The passage in Crespin’s mobiles from order to chaos–depending on whether his forms dilate, diffract or return to the center–reminds us that nothing in the universe is immobile. E pur si muove! (And yet it moves!) as Galileo famously put it back in 1633.

Crespin’s work invites us to reflect on the fundamental questions he holds dear: What is seeing? What is the world around us all about? He says he has always been ‘fascinated by the grandeur and structure of the universe, and by understanding how everything functions and interacts. And by how man has been able to find mathematical representations of how nature functions. Is it in the spirit of man to find representations of nature–or are mathematics an integral part of nature? These are the ideas behind my desire to create air-born choreographies. My work’s technical complexity may be considered as representing the complexity of the universe–with the eye of the viewer like someone observing and pondering the universe.’

Traducción del inglés de Rose Mary Salum

Elias Crespin pertenece al movimiento de Arte Cinético de América Latina y se ha hecho un nombre internacional a través de la ingeniosa belleza de sus móviles electrocinéticos. Su exposición en Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino muestra un conjunto de obras producidas entre 2010 y 2020, que ilustran las distintas etapas de su evolución artística.

Los móviles de Crespin, basados en elementos geométricos repetidos como cuadrados, círculos, puntos y líneas, se despliegan en el espacio en secuencias rítmicas que responden a algoritmos matemáticos. La programación es sofisticada y extremadamente precisa y constituye la culminación de años de investigación que realizó Crespin como ingeniero durante el cambio de milenio. Después de graduarse de la Universidad Central de Venezuela en Caracas, trabajó en la concepción de programas de software especializados antes de aplicar sus conocimientos al campo del arte. El contexto familiar en el que creció también influyó en este cambio de carrera: su abuela fue la artista Gego (1912-94), reconocida por sus trabajos en malla metálica. En Caracas, donde vivió hasta que se mudó a París en 2008, Elias Crespin conoció a gigantes del arte cinético como Otero y Soto, cuyos cubos virtuales decidió poner en movimiento.

Los móviles de Crespin, suspendidos en el aire por hilos invisibles, están imbuidos de un ritmo como el de la respiración. Se van revelando al espectador poco a poco, sin ninguna linealidad mecánica pero con una variedad de efectos sorprendentes. La ultraminimalista Linea Copper (2016) es una estructura lineal que parece afectada por un fenómeno de articulación y dislocación infinita. Los desmaterializados Tetralineados Transparente (2010) llaman la atención a través de sus sombras proyectadas. El suave movimiento ascendente y descendente de Circuconcéntricos Alu Rouge-50 (2018) evoca un mundo vivo; el espectador queda hipnotizado por su relajante construcción concéntrica.

En La Danza de las Catenarias (2019), Crespin explora un mundo de curvas e hilos de lana, cuya estética fluida y vibrante contrasta marcadamente con la mecánica angular de 12 Cubos en Línea Bleu (2020). La configuración volumétrica de este último crea perspectivas largas y ordenadas que dan lugar a estructuras geométricas complejas que, al romperse, desafían la descripción. La malla de cuadrícula regular de 4Net Inox Quadra (2013) parece volar de manera invisible de la form convexa a la cóncava, amenazando con romperse en cualquier segundo. Estas impredecibles metamorfosis atestiguan la infinita imaginación de Crespin, subrayada por su sutil manejo de las cualidades estéticas de sus materiales: la luminosidad transparente o coloreada del plexiglás; la finura gráfica del metal; el contraste entre el metal brilloso y la naturaleza mate de la lana; el impacto de los colores en la definición de una obra…

La mecánica que rige sus móviles permanece invisible y tiene una configuración espacial que emerge poco a poco —alargada en el tiempo, pero no acelerada. El arte programático de Crespin favorece la lentitud sobre la velocidad: estas obras deben observarse con calma. Crean una impresión de ralentización, incluso de suspensión del tiempo, que deja volar la imaginación del espectador. El paso en los móviles de Crespin del orden al caos -dependiendo de si sus formas se dilatan, difractan o vuelven al centro— nos recuerda que nada en el universo es inmóvil. E pur si muove! (¡Y sin embargo se mueve!), como la famosa frase de Galileo en 1633.

El trabajo de Crespin nos invita a reflexionar sobre las preguntas fundamentales que él aprecia: ¿Qué es ver? ¿De qué se trata el mundo que nos rodea? Dice que siempre ha estado “fascinado por la grandeza y la estructura del universo, y por comprender cómo funciona e interactúa todo”. Y por cómo el hombre ha podido encontrar representaciones matemáticas de cómo funciona la naturaleza. ¿Está en el espíritu del hombre encontrar representaciones de la naturaleza, o son las matemáticas una parte integral de la naturaleza? Estas son las ideas detrás de mi deseo de crear coreografías nacidas del aire. Se puede considerar que la complejidad técnica de mi trabajo representa la complejidad del universo, con el ojo del espectador como alguien que observa y reflexiona sobre el universo “.

Con Elias Crespin, la intuición artística y el rigor científico se superponen, provocando una intensa experiencia perceptiva de la que nada te puede distraer. El contacto directo con la obra de Crespin hace que el espectador se deje llevar por la danza lenta y silenciosa de los móviles electrocinéticos cuyas incesantes variaciones, explorando la dimensión imaginaria de nuestra relación con el cosmos, presagian una aproximación verdaderamente poética al espacio.

![Entre Pink Floyd y el INAPAM [1]](https://literalmagazine.com/assets/patti-620x350.png)