Elsa Gramcko: The Path of Intuition, Form, and Things

Fernando Castro R.

The moment on September 1912 when Georges Braque decided to paste a piece of wallpaper onto his painting Fruit dish and glass was pivotal in the history of 20th century art. It shook the very notion of artistic representation and ultimately, of art itself. For, if the former is a depiction of things, and now a thing was part of the representation, what role was it playing? Pablo Picasso was not about to be bested by his French rival and for a period of three years included in his paintings all kinds of things: newspaper clippings, musical scores, parts of musical instruments, tobacco boxes, etc. Braque and Picasso first called the technique papier collé. Later, it came into the art lexicon as “collage,” meaning an assemblage of flat things like photographs, maps, and tickets onto the surface of an art work. However, as things are mostly non-flat, “assemblage” came to signify the additional step towards more inclusive “things.” The German artist and poet Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874-1927), nicknamed “the Dada Baroness,” —active in New York from 1913 to 1923— was perhaps the first woman to try her hand at assemblage. Arguably, these are some of the precedents for the work Elsa Gramcko (1925-1994) produced during one of her most interesting artistic periods in the sixties and seventies in which she included mechanical parts in her assemblages. The following essay engages five periods of her oeuvre.

In the 1960s Elsa Gramcko was one of several Venezuelan artists who produced assemblage art. A brief retrospective exhibition of her oeuvre, The Invisible Plot of Things plots the development of her works from her earliest creative period 1954-1955 up to and including her series Bocetos para un artesano de nuestro tiempo, 1974-1978. The title of the exhibit is well-chosen because what is implicit in her more interesting works that include “things” is more revealing than what is visible.

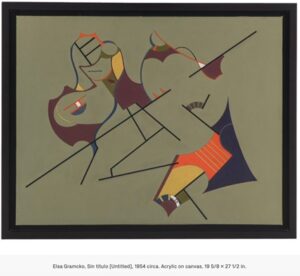

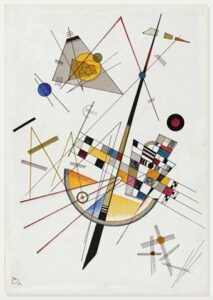

Gabriela Rangel, curator of the exhibit, states that during her brief initial period, “Gramcko developed a medium-size series of oil paintings on canvas constructed with hard lines, irregular shapes, and flat background colors. A few works from this brief period survive.” One of the survivors is included in the exhibit: a small untitled oil on canvas dated 1954 that bears a striking resemblance to the 1923 Wassily Kandinsky’s work Delicate Tension #85. The careful viewer will notice how Gramcko takes her design away from named geometric shapes. Thoughtful deviation from the norm is a pattern that made Gramcko’s oeuvre resistant to easy classification.

Kandinsky, Delicate Tension #85 (1923)

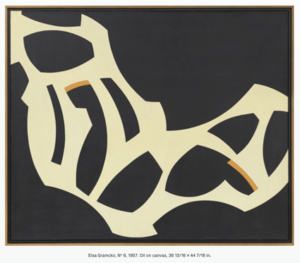

According to Mari Carmen Ramírez, curator of Latin American art at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, during the period from 1954 to 1960 Gramcko produced “a sui generis mode of geometric abstraction.” Given the Kandinsky-like work mentioned above, it is clear that Ramírez is alluding to a different set of works whose mode of abstraction did not fall totally in line with the many ways of producing abstract geometric art up to that time. Indeed, works such as “Untitled, 1956” and “#6, 1957” are uniquely abstract and geometric albeit non-polygonal. It may be misguided to describe them as biomorphic not only because nothing in the biosphere resembles those shapes, but also because it adjudicates to Gramcko a biological interest that she may not have had. If anything, these shapes look like machine gaskets. However, we are playing the wrong game assigning referents to abstract works that aim to be suggestive at most.

An artist close to Gramcko during her formative years was Alejandro Otero who had returned to Caracas from Paris, where he had helped establish the avant garde group Los Disidentes. Rangel adds, “In 1954, Gramcko attended studio art classes at the School of Plastic and Applied Arts of Caracas conducted by Alejandro Otero, a pioneer of geometric abstraction (…).” Otero became Gramcko’s friend and mentor. Not long after her training with Otero, she was invited to participate in the group exhibit “Artistas de la Cuenca del Caribe” that was shown in the Museum of Fine Arts Houston in 1956; and in 1959 she had a solo exhibit at the Art Museum of the Americas in Washington D.C.

For Gramcko the tumultuous decade of 1960 started with a year in which she explored new media. Rangel writes, “The arrival of Informalism to Venezuela in 1959 also coincided with Jesús Rafael Soto’s and Alejandro Otero’s brief explorations of assemblage and collage as reworked by French Nouveau réalisme. (…) Gramcko began a series of black paintings (R) in which she challenged traditional artistic methodologies with the use of an array of industrial materials such as sand, pigments, and glues to produce barren textures with a tactile quality.” Such is the case with R37, 1960, arguably one of Gramcko’s most elegant works and perhaps among her first decisive moves towards Informalism. The thickness of the black acrylic paint mixed with sand resulting in a bas-relief is the kind of technique emphasizing the materiality of the medium favored by Informalist artists like Pierre Soulages or Alberto Burri.

Curiously, Gramcko adamantly rejected aligning her works with Informalism. In a 1976 interview with Juan Calzadilla she stated, “Not a single work of mine is Informalist in the true sense of the term.” However, Mari Carmen Ramirez in her essay Of Things and Machines: Elsa Gramcko’s Journey from the Void to the ‘Real’ unequivocally states, “Despite her work’s idiosyncrasies, her relationship to Informalism has been well established in the literature of her oeuvre.” An important trait of Informalism may explain Gramcko’s recalcitrance: automatism, the creative procedure brought into artistic practice by Dadaist and Surrealist writers. Even Gramcko’s most seemingly random work is far from automatic or gestural; instead, it is methodical and deliberate.

The controversy about Gramcko’s adherence or indifference to Informalism need not opaque the hermeneutic of her oeuvre. It should not impede discussing what is arguably the most interesting period of her oeuvre in which her works turned definitively in the direction of assemblage and thematically into a reflection about “things” and their role both in the individual psyche and within industrial societies. In spite of having a reserved personality, Gramcko was not shy of ideas. Ramírez and Rangel allude to the influence German thinkers Carl Jung and Martin Heidegger may have had in Gramcko’s aesthetic decisions; not to mention her intellectual exchanges with Otero, Calzadilla, Guillent Pérez, and her frequent attendance at the art chats in the Librería Cruz del Sur.

An anecdote, narrated by Gramcko herself, is that her aesthetic shift towards assemblage with found objects came about after the serendipitous discovery of a dilapidated automobile from which she scavenged a number of parts. However, the shift was not as epiphanic as it is portrayed. Before Gramcko started working on her Chatarras assemblages, a few doors were left open for her. For example, there was Soto’s Mural, a 1961 work consisting of wood, wire and a variety of found objects that he allegedly finished in eight hours. Otero himself had produced works that included found objects and materials such as La bisagra roja (1961) and Viva la demolición (1962).

The word “chatarra” stands for old discarded machines or mechanical metal parts that can be used as materials for something else. It is not clear with what criteria Gramcko began to collect chatarra (car battery parts, lighting components, gears, locks, etc.) that she could use in her assemblages. Although some of her Chatarras assemblages are amusing, they are not cheerful. Their muted palette of ochre, rust, and sepia tones is rather subdued. Nonetheless, they are thought-provoking and initially, at least, they expressed a positive attitude about their “things.” In the Chatarras series, meaning gradually emerges from formless matter seeking the structure of found things like machine parts. Hers is a Sehnsucht that also involves playfulness, as evidenced by the marbles she incorporates in works like Comportamiento ante lo real (1966).

Gramcko courageously adhered to her own artistic vision in spite of an art rhetoric that was becoming increasingly political. In a 1961 letter to Otero she wrote, “Day by day, anything that isn’t political or social action is less important, and the situation seems so chaotic that we all feel like we’re on the eve of a catastrophe. And I’m a little bit out of touch, without a doubt, since despite this climate, I’ve been even more involved in my work than ever before.”

In the sixties both Gramcko and Otero produced works where the main support was some kind of door. One by Otero is Bonjour M. Braque (1961), an homage to Braque, who was probably the first artist to include a “thing” in a painting. Gramcko produced many works with doors, including Una pequeña edad (1964). What is key about this particular work is the inclusion of a lock and a ring-type door pull. Even a simple description of it appears as a psychological interpretation because once doors are part of an artwork implicit dichotomies such as open/shut, inside/outside, private/accessible come immediately into mind. It all feeds into the notion that Gramcko was perhaps less reactive and more thoughtful than many artists of her milieu.

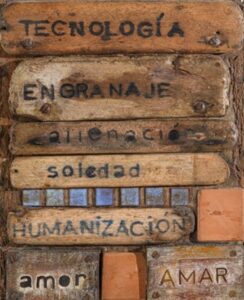

It is during this fruitful period that expands into the 1970s that Gramcko comes up with the series Bocetos de un artesano de nuestro tiempo (Sketches by an Artisan of Our Time). The phrase is cleverly ambiguous between “an artisan belonging to our time” and “his sketches being about our time.” At least two things are different in the works of this new series. First, the kind of things she is using in her assemblages (predominantly worn-out wooden planks). Secondly, she introduces words into some works as if they were “things.” In Número 2 (1976) the words TECNOLOGIA, ENGRANAJE, alienación, soledad, HUMANIZACIÓN, amor, and AMAR are inscribed into small worn-out wooden planks of varying hues. Most of them are words she used in interviews in which she had expressed concerns about dehumanization in the age of technology. Making words central to a work of art was becoming common practice circa 1976 as evidenced by the works of Robert Indiana, Ed Ruscha, Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger.

Implicit in the “things” in Gramcko’s 1970s assemblages is a change in attitude about what the artist wants us to feel and think about them. With the Chatarras series she had us reflecting upon and empathizing with mechanic parts like gears, locks and battery cells. With the Bocetos series we are to embrace the fact that the wooden planks in her assemblages were probably not shaped by heavy industrial machinery, but by artisans whose work is not much different from hers. In an interview Gramcko once stated, “a completely mechanized contemporary society, where man is merely a link in the machinery that places technology before the individual, is the greatest threat to our identity.” To be sure, her insights about a mechanized industrial world from decades ago, before the age of computers, robotics and the Internet, are most relevant today. Moreover, Identity has become central of many an artistic endeavor.

Fernando Castro is an art critic, essayist and curator. He studied philosophy at Rice University thanks to a Fulbright grant. He is a Board Member of FotoFest and the Center for Photography in Houston. His articles have been published by Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal Magazine & Spot among others.

Fernando Castro is an art critic, essayist and curator. He studied philosophy at Rice University thanks to a Fulbright grant. He is a Board Member of FotoFest and the Center for Photography in Houston. His articles have been published by Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal Magazine & Spot among others.

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

Posted: October 3, 2022 at 10:00 pm

Great article, both sensible and clever….totally compelling when analyzing Elsa Gramcko’s oeuvre. In deed her works with “things” are more revealing than what is visible. I agree that …..far from automatic and gestural, Gramcko’s materiality is thoughtful, methodical and deliberate. Unique when using the word “Sehnsucht”…it entails very much her existence. Wooden planks not shaped by heavy industrial machinery, and…..excellent distinction between Gramcko’s aim with Chatarras vs. Bocetos, one gets how still current and important is her discourse. Your article is a relevant spotlight on her legacy, Thanks!!