Kcho: Some Man is an Island

Kcho: Algún hombre es una isla

Fernando Castro

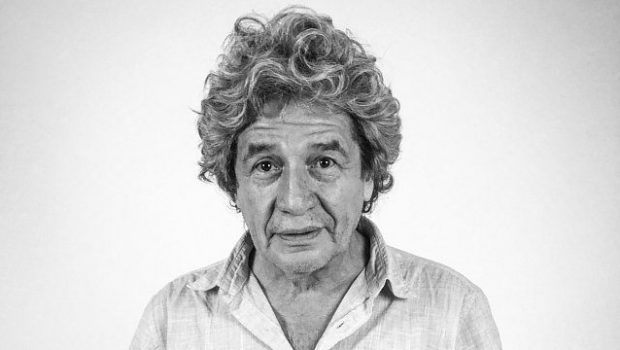

UNFORTUNATELY INTELLIGENCE IS AMONG THE VIRTUES most difficult to possess among those for whom it is always under suspicion of subversion, and the oeuvre of the Cuban artist Kcho is above all intelligent. If Kcho’s oeuvre walks along landmarks that have been and are political it is only because his central concerns—migrations and insularity (particularly, Cuba’s insularity)—implies an ocean of human relations among which is power.

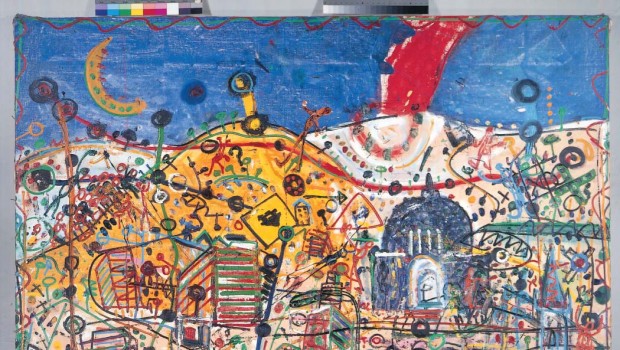

Kcho has stated that his works begin with a title. In fact, his poetics evidences how certain concepts seek to be incarnated in works with which they enter into relations of tension, of metonymy, of contradiction, of metaphor, of irony, etc. The first version of Para olvidar (In Order to Forget, 1995) that Kcho showed at the Kwang-Ju Biennial was a wooden boat floating on bottles. These are two objects of the literature of the sea and of forgetting. On the one hand, the vehicle with which one flees never to come back, or the one with which one returns only to find what is no longer there, or the one with which one simply goes fishing. On the other hand, the empty bottles a drunk gulped down to drown painful memories, or the ones a ship- wreck survivor used to send hundreds of messages that perhaps nobody found, or simply empty liquid containers. Kcho’s oeuvre seems to generate a dialectical movement that makes interpretations swing from one extreme to the other only to settle back into the facts of the raw materials. Both the wooden boat and the glass bottles are blunt as well as fragile objects whose main use is to contain something yet one is meant to keep liquid out and the other one in.

Kcho’s works are usually constructed with second-hand materials and found objects: “I like working with used materials because of the concentrated energy that emanates from them […] I do not work with debris but with past life.” Not surprisingly, Kcho has great admiration for the work of Pablo Picasso (cubist collages) and of Marcel Duchamp (readymades). Some have read into this aspect of Kcho’s poetics a reference to recycling as a way of life for Cubans during the “Special Period” of scarcity that followed the collapse of the Soviet block. It is always possible —and Kcho does little to prevent it—to discover in his works a critical sub-text about the Cuban political situation, but if there is one, it is not a partisan critique, but a reflective and even an existential one.

His ambivalent political-philosophical relation- ship with the Cuban socialist regime may very well be expressed in the work La jungla (The Jungle, 2001)1, a sculptural construction that combines Vladimir Tatlin’s unrealized Monument to the III International (1920) with the erotic anthro- pomorphic bamboo forest of Wilfredo Lam’s mas- terpiece bearing the same name (1943). The III International (1919) was the summit that consolidated communism as the head of the proletarian world movement. Tatlin was commissioned by Lenin to design a wooden model for a monument that—had it been built—would have been 2,000 feet tall. Kcho’s reinterpretation of these works is a fragile tower constructed with slender twigs. It is worth noting that Tatlin—in addition to being the founder of Constructivism—was a sailor and ship carpenter. Is this work a reflection about the construction of the utopian project of a socialist society with the meager materials of scarcity? Does Kcho identify Tatlin, Lam and socialism as paternal figures?

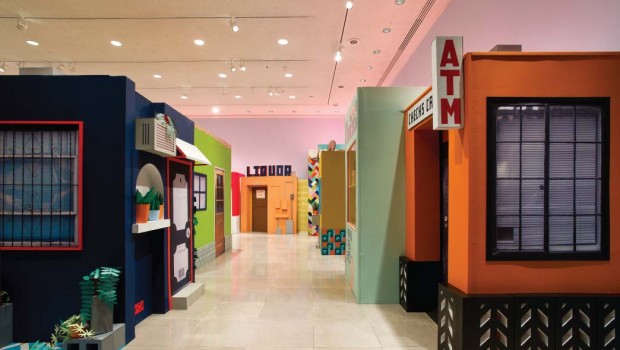

In the Kcho exhibit at the New World Museum (Houston) there is a second version of Para olvidar (In Order to Forget, 2000). In this newer work the boat was replaced by an actual dock which Kcho appropriated and reconstruct- ed. Old tires cushion the impact of boats that might dock there and empty bottles stand where one might expect water. This dock (or one like it)—sans bottles—is part of yet another work called El camino de la nostalgia (The Road to Nostalgia, 1996). These overlaps between different works are an indication of how Kcho’s cre- ative mind works. Suddenly, the same objects— slightly altered—are instances of different con- cepts. Once we replace the dock for the boat we are no longer in transit but waiting for an arrival or in the eve of a departure. The dock is a metaphor for fallible memory. It is the last thing one remembers as one leaves, or it is the first thing one steps onto when one leaves behind what one will forget, or it is the familiarity of daily events that makes us forget the present.

Regata (Regatta,1994), an installation that was shown at the 5th Havana Biennial, is a seminal piece in Kcho’s oeuvre. It consists of dozens of small wooden toy boats, old shoes and other beached debris that come together in the shape of a yet larger boat. The title camouflages with a very Cuban sense of humor what may be going on when a flotilla of vessels suddenly takes a definite direction. “The world is made of migrations,” wrote Kcho. What might be a reference to “Marielitos,” to Elián González, or other local attempts of emigration and exile, Kcho understands as a more general case of the human con- dition. At some point Tainos migrated from one Caribbean island to the other and the Spaniards arrived in a similar way. In recent history, the Vietnamese massively fled their land on board improvised vessels and Mexican natives continue to cross the Rio Grande as they have been doing for thousands of years. Regata brings together the first skills for making wooden toys Kcho learned from his father with the game of making contemporary art.

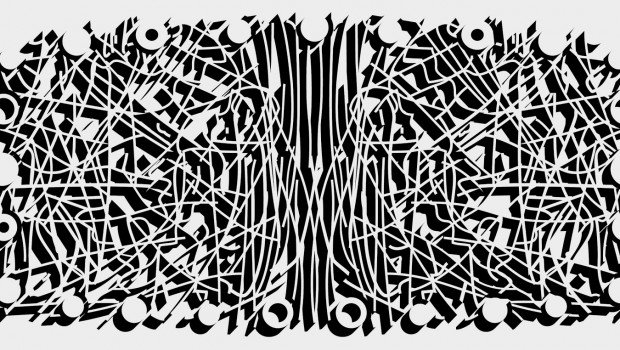

Kcho’s exhibit in Houston included several drawings. Although Kcho once expressed a cer- tain disdain for painting, drawing is the instrument of his visual thinking. Drawing is so important for him that the work that he presented at the Venice Biennial—although not a drawing but rather an installation shaped like boat by a row of chairs—is titled Sólo cuando dibujo comprendo lo que pienso (Only when I draw I understand what I think,1999). The rhetoric of Kcho’s draw- ings bears some resemblance to those of the South African artist William Kentridge although for the latter they are always the vehicles for animated videos whereas por Kcho they are either ends-in-themselves or ideas destined to become installations. Says Kcho, “I like drawing because of its intensity; it is like poetry.” In fact, the objects he draws are intensely poetic: propellers, oars, tire tubes, huts, boats, docks, etc.

The polyptych Binocularsis a series of drawings grouped in five panels. They resemble the vision of someone who observes a group of people aboard boats through binoculars. In these drawings (albeit not in binocular vision) the por- tion of the visual field the right eye sees is different from what the left eye sees. In one case, the left eye sees an armed man aboard the boat that the right eye does not see. This type of ambiguity is frequent in Kcho’s oeuvre. When one sees these drawings one is prompted to ask many questions. Who observes? Is it the Cuban Coast Guard or the U.S. Coast Guard? Is it a neutral observer? Who is observed? Are they coming or going and where?

Kcho: “I have never understood why in Cuba, being an island, the sea is considered dangerous, when it should be something very close and loved. It is certainly risky and beautiful, but everything that defines what Cuba is has arrived by the sea.”

Ironically, Kcho can leave the island of Cuba freely but so far the American museums that have shown his work have been unable to procure him a visa to cross the sea into the United States.

NOTES

1 This work is a reinterpretation of an earlier one by Kcho: A los ojos de la historia (Before the Eyes of History,1992) that included a conical coffee filter at the tower’s highest point.

2 We thank Armando Palacios, director of the New World Museum, and to Roberto Borlenghi, proprietor, Janda Wetherington, director of the Pan-American Art Gallery, for their priceless collaboration and information

DESAFORTUNADAMENTE LA INTELIGENCIA ES UNA DE LAS virtudes más difíciles de poseer entre quienes ésta siempre está bajo sospecha de subversión, y la obra del artista cubano Kcho es sobretodo inteligente. Si la obra de Kcho transita por hitos que han sido y son políticos es porque sus preo- cupaciones centrales —las migraciones y la insularidad (en particular, la insularidad de Cuba)— implica un océano de relaciones humanas entre las que figuran las del poder.

Kcho ha manifestado que sus obras comienzan con un título. De hecho, su poética pone en evidencia cómo ciertos conceptos buscan encarnación en obras con las que consecuentemente entran en relaciones de tensión, de metonimia, de contradicción, de metáfora, de ironía, etc. La primera versión de Para olvidar (1995), que Kcho mostró en la Bienal de Kwang-Ju, era un bote flotando sobre botellas. He aquí dos objetos de la literatura del mar y del olvido. Por un lado el vehículo con el que se huye para no volver, o con el que se regresa para ya no hallar lo esperado o con el que simplemente se pesca. Por otro lado, las botellas vacías que algún ebrio consumió para entumecer las memorias, o las que un náufrago usó para enviar cientos de mensajes que quizá nadie halló o las que simplemente se usan para contener líquidos. La obra de Kcho parece generar un movimiento dialéctico que empuja las interpretaciones de un extremo a otro, sólo para resolverse al final en los hechos de la materia prima. Tanto el bote de madera como la botella de vidrio son objetos contundentes y a la vez frágiles cuyo uso principal es contener algo; sólo que el primero debe mantener afuera el líquido mientras que el segundo está diseñado para tenerlo adentro.

Por lo general las obras de Kcho están hechas con materiales ya usados y objetos hallados: “Me gusta trabajar con los materiales usados, por la energía concentrada que emana de ellos […] Yo no trabajo con desechos, sino con vida pasada”. No debe sorprendernos entonces su admiración por Pablo Picasso (collages cubistas) y por Marcel Duchamp (readymades). Hay quienes han visto en esta poética de Kcho una referencia al reciclaje como modo de vida de los cubanos durante el “período especial” de escasez que comenzó tras la caída del bloque soviético. Siempre es posible —y Kcho no hace mucho por evitarlo— descubrir en su obra un subtexto crítico de la situación política cubana; pero si la hay, no es una crítica partidaria, sino una crítica reflexiva e incluso existencial.

Sus ambivalentes relaciones filosófico-políticas con el régimen socialista cubano bien podrían expresarse en su obra La Jungla (2001), una construcción escultural que combina el nunca realizado Monumento a la III Internacional (1920) de Vladimir Tatlin con los cañaverales eróticoantropomórficos de la obra maestra de Wilfredo Lam que lleva el mismo título (1943). La III Internacional (1919) fue la cima que consolidó al comunismo como cabeza del movimiento mundial del proletariado. Tatlin fue comisionado por Lenin para diseñar un modelo en madera del monumento que —de haber sido realizado— habría tenido 2,000 pies de altura. La reinterpretación de Kcho de ambas obras es una endeble torre construída con delgadas ramas. Es importante notar que Tatlin —además de fundador del Constructivismo— fue marino y carpintero de barco. ¿Es esta obra una reflexión sobre la cons- trucción del proyecto utópico de una sociedad socialista con los frágiles materiales de la esca- sez? ¿Identifica Kcho a Tatlin, a Lam y al socialismo como figuras paternales?

En la exhibición de Kcho en el New World Museum (Houston) hubo también una segunda versión de Para olvidar (2000). En ésta el bote fue reemplazado por un muelle de verdad apropiado y reconstruído por Kcho. Llantas viejas amorti- guan el impacto de los botes que puedan atracar en él y hay botellas vacías donde uno esperaría que hubiera agua. Este muelle (o uno parecido) —sin las botellas— es parte de una tercera obra llamada El Camino de la nostalgia (1996). Las semejanzas entre diversas obras es una indicación de cómo funciona la mente creativa de Kcho. De pronto, los mismos objetos —con ligeros cambios— son instancias de diferentes conceptos. Al sustituir el muelle por el bote ya no estamos en tránsito sino en espera de una llegada o a vísperas de una partida. El muelle es metáfora de la memoria falible. Es lo último que se recuerda al partir, o es lo primero que se pisa al dejar atrás lo que se ha de olvidar, o es la familiaridad de lo cotidiano que nos hace olvidar lo presente.

La regata(1994), instalación que se exhibió en la 5a Bienal de La Habana, es central en la obra kchiana. Consta de docenas de pequeños botes de juguete, zapatos viejos y otros escombros playeros que a su vez dibujan la forma de una embarcación mayor. El título disfraza con un humor muy cubano lo que pudiera estar pasan- do cuando una flotilla de embarcaciones toma un rumbo definido. “El mundo está hecho de migraciones”, ha escrito Kcho. Lo que pudiera ser una referencia a los “marielitos”, a Elíán González o a otros intentos locales de emigración o exilio; Kcho lo entiende como un caso más general de la condición humana. Alguna vez los taínos migraron de isla en isla caribeña y los españoles llegaron a Cuba de manera similar. En la historia reciente los vietnamitas huyeron masiva- mente de su tierra en embarcaciones improvisadas y los nativos mexicanos siguen cruzando el Río Grande como lo han venido haciendo por miles de años. La regata reúne las primeras destrezas de carpintería que Kcho aprendió de su padre para hacer juguetes con el objeto de hacer arte contemporáneo.

La exhibición de Kcho en Houston incluyó varios dibujos. Aunque Kcho alguna vez ha expresado cierto desdén por la pintura, el dibujo es el instrumento de su pensamiento visual. El dibujo es tan importante para él que la obra que presentó en la Bienal de Venecia —aunque no es dibujo sino una instalación con forma de bote sugerida por una hilera de sillas —se titula Sólo cuando dibujo comprendo lo que pienso (1999). La retórica de los dibujos de Kcho se asemeja a los dibujos del sudafricano William Kentridge, aunque para éste ellos son siempre vehículos para el video animado mientras que para Kcho son fines en sí mismos o medios con destino de instalación. Dice Kcho: “El dibujo me gusta por su intensidad, es como la poesía”. De hecho, los objetos que dibuja son intensamente poéticos: hélices, remos, neumáticos de llanta, chozas, botes, muelles, etc.

El políptico Binoculares es una serie de dibujos agrupados en cinco paneles. Remedan la visión de alguien que divisa a través de binoculares a un grupo de gente a bordo de barcazas. En estos dibujos (mas no en la visión binocular) lo que el ojo derecho ve es ligeramente distinto a lo que ve el ojo izquierdo. En un caso, el ojo izquierdo ve a alguien armado a bordo del bote que el ojo derecho no ve. Este es el tipo de ambigüedad que abunda en la obra de Kcho. Al ver estos dibujos uno se hace muchas preguntas. ¿Quién observa? ¿Es la guardia costera cubana o la guardia costera estadounidense? ¿Es un observador neutral? ¿Quiénes son observados? ¿A dónde van? ¿Llegan o se van?

Kcho: “Nunca he entendido por qué en Cuba, siendo una isla, al mar se le ve como un peligro, cuando debe ser algo tan cercano, tan querido. Es cierto que a la vez es hermoso y riesgoso, pero todo lo que define a Cuba ha llegado por el mar”.

Irónicamente, Kcho puede salir de la isla de Cuba libremente, pero hasta ahora los museos estadounidenses que han mostrado su obra no han podido conseguirle visa para que pueda cru zar el mar hasta los Estados Unidos.

NOTAS

1 Esta obra es una reinterpretación de una obra anterior de Kcho: A los ojos de la historia (1992), que incluía un filtro de café cónico en la cima de la torre.

2 Agradecemos a Armando Palacios, director del New World Museum, a Roberto Borlenghi, propietario, y a Janda Wetherington, directora de la Pan-American Art Gallery, por su invalorable colaboración e información.

Hello!

I would like to reference this article about Kcho from issue 3 in my dissertation. However, I cannot find the publishing date, I’m afraid. I would be grateful if you could help.

Thanks and regards,

Heike