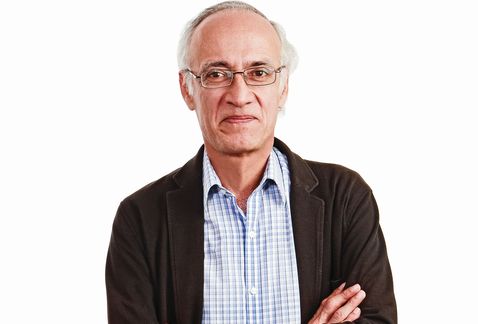

The Excessive Imagination, Interview with Francisco Hinojosa

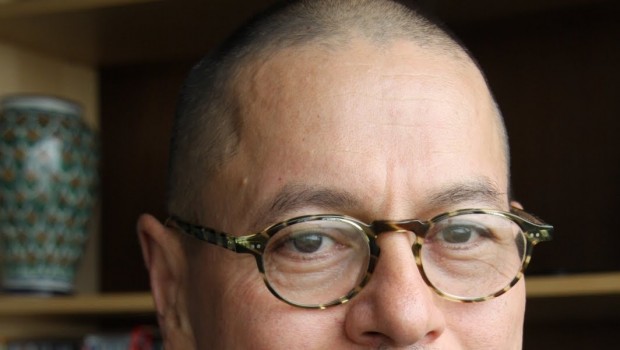

Socorro Venegas

Mexican writer Francisco Hinojosa can presume to have impacted thousands of readers who have read his work since they were young children. And to have impacted them, now grown, to the point where they buy his books again on the pretext of reading them to some niece or nephew or younger sibling this time.

Another facet of Francisco Hinojosa, neither less original nor entertaining, is his excellent adult literature. In the terrain of children’s fiction, Juan Villoro has baptized Hinojosa “the Brother Grimm;” in his story production for adults, the Mexican literary critic, Christopher Dominguez Michael, has christened him the most original of the Mexican storytellers and one of the “most delightfully-biting wits” of contemporary literature in the Spanish language.

This interview took place in Cuernavaca, only an hour from Mexico City, a place where he has lived for some years and where he shares life and literature with his wife, the talented and renowned poet, María Baranda, and with a growing community of artists and writers who seem to found something of the same fervent creative atmosphere in this city that inspired Malcolm Lowry to write his novel, Below the Volcano.

* * *

Socorro Venegas: What motives are there, what changes the creative process, when you write for a child and when you do it for an adult?

Francisco Hinojosa: There’s a sense of enthusiasm. I believe that when I write for children, I truly am a child, I put myself in the role of reader and that’s what makes the difference. And, I laugh distinctly differently in the case of writing for children rather than how I laugh when I write stories for adults.

SV: One time you said, “After so many years, I’ve got it straight that if I write a story for children and they don’t like it, or it doesn’t interest them, it’s my fault. Conversely, if I do something for adults, and they don’t like it, it’s the reader’s fault. Can you expand on this idea?

FH: I believe that when a child reads a story that doesn’t interest him, that has a bad beginning, that doesn’t correspond to his sphere of interest, that he doesn’t like, that doesn’t make him laugh, the one who is failing is the author who didn’t find out how to en- gage that child reader until he’s well into the story. This is why I say that, when a child reader isn’t interested in the story and tosses it away, the author has died.

SV: The readers of your children’s stories have consolidated your status as one of the most read authors. How have you done with the readers of your stories for adults?

FH: Response is very meager. I believe that, in the case of children, I am an author who gets printed a lot, who gets read a lot, that’s unquestioned, the numbers support it. But the numbers also say something else when they refer to the books that I have published for adults. It’s an absolute fact that the three books of my books published by Tusquets have sold around 15 copies in the past year. That says something about the story, that in general, as a genre, it doesn’t get read much. I believe that I am an author, in the case of literature for adults, much more for a specific audience, for a particular kind of reader, and almost always, as I have told those few readers among adolescents, that this is something that pleases me a lot. And, I don’t care about being much more widely read.

SV: Returning to children’s literature, at some conferences, you have referred to the experience that North American editors of children’s literature have a list of prohibited topics.

FH: Yes, there is a kind of requirement that the authors of books for children must be politically correct. The academically-oriented system doesn’t accept certain books that contain topics not considered appropriate for children, like war, violence, drugs, but also among those prohibited topics are rock music, candies, dinosaurs, excessive fantasy, and one that surprised me a lot, in one publishing proposal made to me by some editors, houses with swimming pools. The idea is that a ficticious house with a pool in a story may make some child reader who doesn’t live in a house with a pool feel bad. I believe that, if this concept were true, practically all classic literature would be banned.

SV: In Mexico, have you also encountered prohibited topics, even if not on a formal list?

FH: I don’t think so right now. Fifteen years ago, it was difficult to address certain topics. I remember that, back then when I published The Worst Lady in the World, the book came out in spite of three recommendations against it; the editor, Daniel Goldin, published it because he believed in it. It came out as a very small print-run, two thousand copies, that, little by little, got sold. In some schools, the book was banned. My own friends said that they weren’t sure about teaching a story like this to their children. It’s a situation that has changed over time. Today the quantity of books that deal with topics of this kind, like violence, vulgarity or death, has grown. Today we find The Book of Dirty Words, just published by Julieta Fierro and Juan Tonda, that has had incredible success. A book like this fifteen years ago was unpublishable. I believe that, in this sense in Mexico, yes, we have moved forward and that today the teachers, the parents, the proponents of reading, are much more open, they know that these topics DO figure directly in what child readers like.

SV: If you had to make a list of prohibited topics in children’s literature, what would you ban?

FH: I’d ban warm-fuzzy stories, excessive seriousness, the use of baby-talk and all those things which don’t recognize the child as a more demanding reader than the adult.

SV: Do you believe that more “difficult” topics are acceptable today thanks to television or internet, which have reduced the shock factor, or has it been the fact that one reads about them more?

FH: I believe that we have face-off here: technology versus literature. Today the most read book, not only by children, but of all books published, is Harry Potter, a novel that ignores technology. There aren’t any computers, there isn’t any electric light. What there is, is a delightful excess of fantasy. I feel that there is a type of nostalgia for surprise, nostalgia for that capacity to fantasize, that counterpoints that technology, that doesn’t surprise us for nothing. If you take your tape recorder and you transform it into an espresso machine, nobody will be surprised. In contrast, yes, a unicorn is still going to astound us, and all the fantastic zoology that Harry Potter presents. I believe that good literature—not children’s books but literature for children—is helping television or computer games to co-exist in harmony with stories. I don’t want to say that it’s necessary to pit television against reading, I believe that the two can co-exist.

SV: Now that you mention the “excess of fantasy” in Harry Potter, I remember having read a review of a novel that I like a lot, Forever in Check, by Gonzalo Lizardo, where the author is accused of an excess of imagination. What do you think of this?

FH: Today this inner-conflict exists in readers, especially adult readers, a fear of imagination. A novel which has basis in the history, in the political and social reality of the country or the world, has a meaning. But when things get mixed up in that other kind of trip via the imagination, many feel that it’s dangerous, that it runs counter to a grounding in reality and that we can come to lose sight of the it. I think totally the opposite: as a result of reading books about imagination, about fantasy, you can come to understand reality much better.

SV: In one of your stories, Campus Life, you refer to a cancellation of classes in a big university. It is unavoidable to think immediately of the National Autonomous University of Mexico and the recent conflicts there that led to the standstill. It turned out to be an almost prophetic text because it was written and published before the events about which it told.

FH: Yes, it could have seemed prophetic; I don’t believe that it was. In the final analysis, it is something that is in the atmosphere, it’s the conflict that can exist in education. At the first of the current administration, it’s in what budget allocations tried to punish the most, the line item of education. The president believes that it is necessary to invest in the fight against poverty, in combating delinquency, in the stimulation of rural life, etc. I believe that if we start out with education, it will come to combat poverty, insecurity, something that our elected officials have never seen that way. In the air, there was this possibility that one day the universities would turn into the equivalents of big stores and leave off educating itself.

SV: And you have another story, Planted, which talks about that real-life incident when the prosecutor was mixed up with a hypothetical prophet to carry out a clandestine burial.

FH: That was due to a proposal by Marin Solares who asked different writers to take a topic from national political or social reality and transform it into a story, coming out of the gist of what Carlos Fuentes was saying: that reality is robbing writers of plots. Today, if we made synopsis of what happened with Carlos and Raul Salinas de Gortari, with Gloria Trevi, or with the pedophilic priests, etc., we would read it as if it were fiction. We’d ask ourselves, What kind of perverse mind thinks up such a mind-boggling story? I have another prior story that also comes out of a certain reading of reality: when the previous president, Vicente Fox, won the elections, I imagined what would happen if two guys came to the president and told him that they wanted to buy the country and they wanted to run it as if it were a private enterprise. Even though the story is mind-boggling, the consequences from Fox aren’t so far from that.

Posted: April 10, 2012 at 6:20 pm