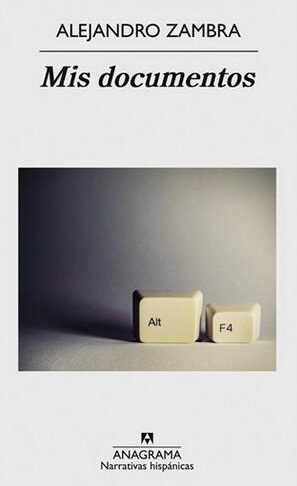

On Alejandro Zambra’s My Documents

Susannah Rodríguez Drissi

If Latin American literature has entered the twenty-first century, then Alejandro Zambra’s My Documents may be just the book that most closely hews to its new preoccupations. My Documents is Zambra’s fourth book in the narrative genre; it is also the longest (the first was Bonsai, weighing in at approximately 86 pages) and the first in the short story category. Published this last April in an English translation by Megan McDowell, the collection is a far and pixelated cry from the tales (and tails) of Macondo. Having read Bonsai in both English and Spanish and loved it for reasons I shan’t go into here —let us just say that they have to do with literature in its broadest sense—, it was with great anticipation that I arrived at a Coffee Bean on West Pico Boulevard in Los Angeles with a borrowed galley of My Documents in my bag and a red pen for that yet-to-be revised mistranslation.

I went in, ordered a cold latte (regular), and waited for a table to clear, ending up 10 minutes later in a corner by the front window. I sipped my coffee from a straw, ignored the barking Terrier on the other side of the glass, and read in a most disorderly fashion—pulling a Cortázar and hopscotching my way from the third story to the first, then turning to whichever direction my fancy dictated. I tried in earnest to find flaws with the translation and dodge my own anxiety about anything called “my documents.” But, alas, I forgot I was reading in English and, as it happens with my own documents—those I have named, saved, and filed somewhere in a folder by the same name—these “documents” were meant to be accessed in no particular order.

Zambra was born in Santiago, Chile in 1975. In 2007, he was included, along with Junot Díaz (The Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao), Wendy Guerra (Everyone Leaves), and Daniel Alarcón (Lost City Radio) among others, in Bogotá39, a collaborative project between the Hay Festival and Bogotá: UNESCO World Book Capital City 2007 that identified 39 of the most promising Latin American writers under the age of 39. Since then, he has published The Private Lives of Trees (2010) and Ways of Going Home (2013), both translated into English by McDowell and both—much like Bonsai—belong to the featherweight category: The Private Lives of Trees comes in at 98 pages and Ways of Going Home at 160. Certainly, My Documents constitutes a new heavy but, at 241 pages, it is by no means hefty.

As the title of the collection alerts us, this book constitutes a kind of “archive,” but not in the sense that we might expect given Zambra’s Latin American background. This is not rural Latin America in the likes of Gabriel García Márquez circa 1967. This is millennial Chile and all moves at the speed of gigabytes (or Lionel Messi on the field). There are no butterflies or pigs’ tails here. The stories in this collection belong to a Latin American urban space and, specifically, to a Chilean social reality where exile, disenchantment, computers, soccer, The Sex Pistols, and Pinochet (or, at least his specter in a period of transition) share the space. What we have are two kinds of “small” stories: those that remit the reader to the author’s own life belong to a first-person narrator; the rest, to a third-person point of view that relates the “small” lives of others. My favorite in the first category are the title story, “My Documents”, and “I Smoked Very Well.” I like the first one because it speaks to me of a childhood I had yet to read about in someone else’s writing: my own. And the second one, well, it restores a certain character to smoking that in English translation may become both foreign and politically incorrect.

“I Smoked the Last Cigarette” begins as follows:

The treatment lasts for ninety days. Today is the fourteenth day. According to the information pamphlet, I get one last cigarette. The last cigarette of my life. (137)

The story concludes like this:

It’s bad for me, so I will never smoke again. But first, I want to have one last cigarette. One more. A thousand more. I’m only going to smoke a thousand more. The final thousand cigarettes of my life.

The other stories, told from a third-person perspective, take up—among other things—the difficulty in establishing long-lasting romantic relationships. Such is the case of “Family Life.” Referring to Martin, a recently divorced forty-something, the narrator tells us:

The other stories, told from a third-person perspective, take up—among other things—the difficulty in establishing long-lasting romantic relationships. Such is the case of “Family Life.” Referring to Martin, a recently divorced forty-something, the narrator tells us:

[He] launches into a monologue about the past, in which brushstrokes of the truth are mixed with some obligatory lies, as he searches for a way of being honest, or at least less dishonest. He talks about pain, about the difficulty of building long-lasting, simple ties with people. “I’m addicted to the drug of solitude.” (216)

Much like the content or “stories” we file/save in the My Documents folder in our PCs, these stories at once seem to belong in their assigned “folder” and also to be misfiled; in other words, the “My Documents” that allude to one’s own life and one’s national identity or citizenship end up projecting the personal to various parts of the globe. Ultimately, these stories which at some point may have belonged to a single narrator—the author’s double, perhaps?—are launched onto a shared social space. They move fast. If they ever slow down long enough to belong, they only do so in order to belong to everyone.

I’m back home now and it’s 8:32 PM. I place the galleys and the red pen on a small side table in my office. I make small piles out of the papers scattered on the floor and set them down on a nearby couch: “In progress” on one side and “For tomorrow,” on the other. I stack books against a wall to clear a small space on my desk. I open my laptop and look for “My Documents”—where, I wonder, should I file the rest?

MY DOCUMENTS

By Alejandro Zambra

Translated by Megan McDowell

241 pp. McSweeney’s. Paper, $15.

Posted: July 9, 2015 at 10:43 pm