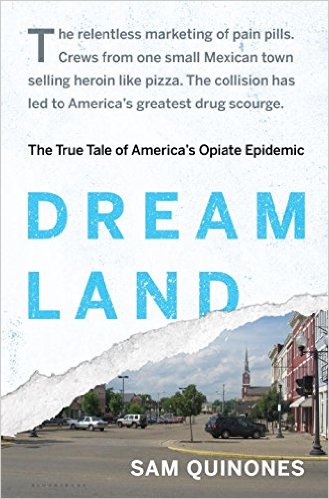

DREAMLAND: THE TRUE TALE OF AMERICA’S OPIATE EPIDEMIC

C.M. Mayo

This is a grenade of a book. Based on extensive investigative reporting on both sides of the U.S.- Mexico border, Sam Quinones’ Dreamland tells the deeply unsettling story of the production, smuggling, and marketing of semi-processed opium base— or “black tar heroin”— originating in and around Xalisco, a farm town in the state of Nayarit, and in tandem, the story of the aggressive marketing of pain pills in the U.S.— in particular, of Purdue Pharma’s OxyContin—and the resulting conflagration of addiction and death.

Unlike previous drug epidemics—heroin in the 70s, crack in the 90s— this one involved more deaths and more users, and not so many in urban slums but “in communities where the driveways were clean, the cars were new, and the shopping centers attracted congregations of Starbucks, Home Depot, CVS, and Applebee’s.”

Mexican black tar heroin trafficking isn’t anything like what you’ve seen on TV or in the movies or, for that matter, most books about narcotrafficking. It’s a small-time and customer-centric business: smugglers carry small high-quality batches over the border, and then drivers, using codes received on their cell phones, deliver tiny balloons filled with heroin directly to individual customers. The smugglers and drivers, “Xalisco Boys,” for the most part— friends, neighbors, brothers, third cousins— are not ready-for-prime-time “narcos” but otherwise ordinary young men from an otherwise ordinary farm town.

Nor are these Mexicans crossing the border because they are drawn by the light of “a better life” in the U.S. Their goal is a short period of hard work—and if that work happens to be delivering balloons filled with some drug to gringo addicts, so be it—and then to return home with the cash to peel off for a house, a wedding banquet with a live band, a stack of Levi’s jeans for the clan.

The number of English language reporters who could have written such a book can be counted on one hand— if that. Quinones draws on two decades of covering remote corners of Mexico and Mexican immigrants to the U.S. His two previous books, both superb, are True Tales from Another Mexico: The Lynch Mob, the Popsicle Kings, Chalino, and the Bronx and Antonio’s Gun and Delfino’s Dream: True Tales of Mexican Migration. In Dreamland, Quinones writes about the “Xalisco Boys” with unusual insight and compassion; nonetheless, in their numbers and moral blindness, they have an ant-like quality. As one DEA agent told Quinones, “We arrest the drivers all the time and they send new ones up from Mexico… They never go away.”

Neither are their customers, “slaves to an unseen molecule,” what one might expect: oftentimes well-off people living in places like Salt Lake City, Charlotte, Minneapolis or say, Columbus, Ohio. Writes Quinones:

“Via pills, heroin had entered the mainstream.The new addicts were football players and cheerleaders; football was almost a gateway to opiate addiction. Wounded soldiers returned from Afghanistan hooked on pain pills and died in America. Kids got hooked in college and died there. Some of these addicts were from rough corners of rural Appalachia. But many more were from the U.S. middle class… They were the daughters of preachers, the sons of cops and doctors, the children of contractors and teachers and business owners and bankers. And almost every one was white.”

As Quinones explains, the use of opiates is ancient, going back to the Mesopotamians who harvested poppies—“joy plants”— for their pods containing opium. The Egyptians produced opium as drug. In the early 19th century, a German chemist came up with the extract known as morphine; later in that same century, another German chemist brought us heroin, and China lost its two Opium Wars to the British, arriving at the turn of the century with a prodigious number of addicts. In the U.S. in the early twentieth century, a government-led campaign to outlaw addictive drugs may have decreased the number of “dope fiends,” but it resulted in the growth of illegal drug dealing by mafias and gangs, many of them prone to extreme violence.

The game-changer has been the Xalisco Boys’ marketing and distribution model for black tar heroin—Quinones likens it to pizza delivery— coinciding with the aggressive marketing of legal opiates such as OxyContin—which are more expensive than, but in terms of effects, close substitutes for Mexican tar heroin.

As for the marketing of pharmaceuticals, Quinones devotes an illuminating chapter to marketing guru Arthur Sackler and his work for Charles Pfizer and Company back in the 1950s, when he turned Pfizer “into a household name among doctors.” Things took a bum turn in the mid-1980s when two pain specialists, Russell Porteney and Kathy Foley, published a paper in a medical journal, Pain, suggesting that opiates might not be inherently addictive. In a footnote they cited a letter to editor of the New England Journal of Medicine from Jane Porter and Hershel Jick. Soon thereafter, Portenoy assumed a prestigious position: Director of the Pain Medicine and Palliative Care department at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City. Writes Quinones: “From this vantage point, and with funding from several drug companies, he pressed a campaign to destigmatize opiates.”

Enter Purdue Pharma with its new painkiller, OxyContin, an opium derivative with a molecular structure similar to heroin. Somehow in all the hoopla, Porter and Jick’s letter to the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine— not a report, and certainly not a study, but a mere one-paragraph note that less than one percent of hospitalized patients receiving opiates for pain became addicted— “had become a foundation for a revolution in U.S. medical practice.”

It seems few troubled to read said letter; armies of sales reps marched out citing “Porter and Jick” and—magic gong— the New England Journal of Medicine. As one nurse told Quinones, “Everybody heard it everywhere. It was Porter and Jick. We all used it. We all thought it was gospel.”

Quinones is careful to note that OxyContin “has legitimate medical uses, and has assuaged the pain of many Americans, for whom life would otherwise be torture.” But in fact, like heroin, its close chemical cousin, it is highly addictive. As one addict, a prison guard who had started off with OxyContin for back pain and, in agony from withdrawal, ended up on black tar heroin, told Quinones,

“You think you’re doing stuff the way it’s supposed to be done. You’re trusting the doctor. After a while you realize this isn’t right but there really isn’t anything you can do about it. You’re stuck. You’re addicted.”

Dreamland, a football-field-sized private swimming pool in Portsmouth, Ohio is the touchstone for Quinones’ narrative. For decades after it opened in 1929, Dreamland served as a center for the community, whose prosperity was based on a steel mill and shoe factories. Anyone who has traveled through the U.S. in recent years will have seen the same decline Quinones describes here and in so many other towns: the Mom and Pop diner replaced by a Subway sandwich shop or an Applebee’s or a Jack in the Box; the family-run hardware store and grocers, overtaken by Walmart and Home Depot; ye olde bookshop shuttered and scribbled with graffiti. (There might be, but probably isn’t a Barnes & Noble.) And the big box stores are not wedged into in the now decrepit downtown but sit on the outskirts where real estate is cheap, zoning whatever, and parking an easy swing.

As jobs went abroad, Portmouth’s businesses began to close, and “pill mills,” that is, pain clinics specializing in dispensing drugs such as OxyContin, began to open. In 1993, Dreamland was razed to make a parking lot. Writes Quinones

“After Dreamland closed, the town went indoors. Police took the place of the communal adult supervision that the pool had provided. Walmart became the place to socialize. Opiates, the most private and selfish of drugs, moved in and made easy work of a landscape stripped of any communal girding.”

It was the historian of Mexico John Tutino who said, “We need Mexico as an other. We cannot deal with it as an us.” Too many U.S. policymakers and pundits are quick-on-the-trigger to blame the drug trade on Mexican corruption. But supply responds to demand and the corruption that makes the drug trade possible thrives on both sides of the border. Yes, even in the nicely appointed offices of a major pharmaceutical company. In 2005 Purdue Pharma pleaded guilty to a felony count of “misbranding” OxyContin as less addictive than other pain medications. None of its executives went to jail, but three paid a USD $34.5 million fine and the company itself paid a US $634.5 million fine.

Dreamland should be read—and more than once— by anyone who would make or attempt influence policy on the drug trade, whether legal or illegal. Moreover, Dreamland should be read by every citizen who would visit a doctor. As Quinones wrote in a recent New York Times opinion piece, apropos of Dreamland, “we need to question the drugs marketed to us, depend less on pills as solutions and stop demanding that doctors magically fix us. It will then matter less what new product a drug company—or the drug underworld—devises.”

C.M. Mayo es novelista, ensayista y traductora literaria, Es la autora de la novela El último príncipe del Imperio Mexicano y Odisea metafísica hacia la Revolución Mexicana:Francisco I. Madero y su libro secreto, Manual espírita, ambos traducidos del inglés por Agustín Cadena. Entre sus otros libros se encuentra Miraculous Air: Journey of a Thousand Miles through Baja California, the Other Mexico (Milkweed Editions, 2007 y University of Utah Press, 2002)

C.M. Mayo es novelista, ensayista y traductora literaria, Es la autora de la novela El último príncipe del Imperio Mexicano y Odisea metafísica hacia la Revolución Mexicana:Francisco I. Madero y su libro secreto, Manual espírita, ambos traducidos del inglés por Agustín Cadena. Entre sus otros libros se encuentra Miraculous Air: Journey of a Thousand Miles through Baja California, the Other Mexico (Milkweed Editions, 2007 y University of Utah Press, 2002)

©Literal Publishing

Posted: October 11, 2015 at 9:22 pm

I loved this article