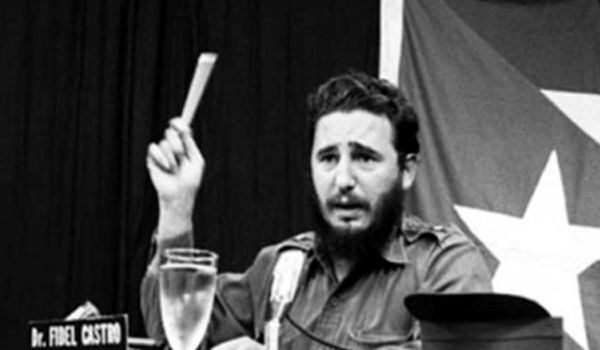

Fidel Castro’s “Words to Intellectuals” at 60: Nothing to Celebrate

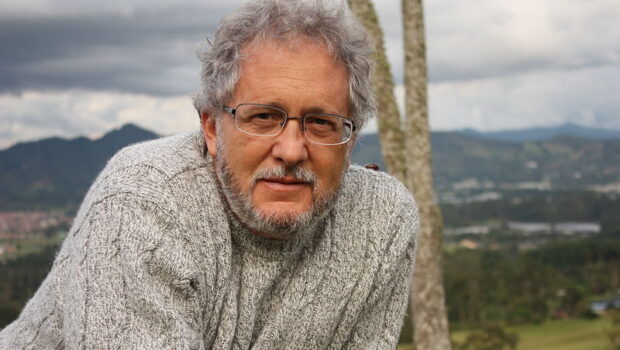

Yvon Grenier

This is the 60th Anniversary of Fidel Castro’s speech, “Words to Intellectuals” (1961), one of his most important speech and arguably the most important document anchoring state control of public speech in Cuba. For freedom loving artists and intellectuals, in Cuba and beyond, there is nothing to celebrate.

It is discussed often and with utmost veneration in Cuba, as if it was a sort of revolutionary hadith (the words of the prophet in Islam), usually with the objective to prove that Fidel was right then and all along. If mistakes have been made, squeezing a little too hard on the very limited freedom afforded by artists, it was because of a failure to properly comprehend his message.

This was a two-and-a-half hour speech, so relatively short by Fidel Castro’s standards, delivered during the last of the three meetings (16th, 23rd and 30th of June) between writers and artists, on one hand, and political officials on the other. Were present, in addition to Fidel Castro, Cuba’s nominal President Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado, the Minister of education Armando Hart Dávalos, the president of the Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (ICAIC), Alfredo Guevara, the members of the Consejo Nacional de Cultura and other government figures.

These reunions were made necessary to clear the air in the literary and artistic community after the regime’s first overt act of censorship, against a short (13 minute) and apparently innocuous cinéma vérité film/documentary, produced in December 1960-January 1961. “PM” (for “Pasado Meridiano”) simply features scenes of Havana nightlife. There are no comments, only great music and folks having a good time–ostensibly, rather than building socialism or defending the revolution against U.S. aggression, as was the order of the day a few weeks after the Bay of Pigs invasion.

As writer Guillermo Cabrera Infante wrote, PM “is a cinematic mural about the end of an era.” It was realized by two young filmmakers, Sabá Cabrera Infante (brother of Guillermo) and Orlando Jiménez Leal, associated with one of the two groups competing for Fidel’s recognition in the cultural field. Cabrera Infante was the editor-in-chief of Lunes de Revolución. The film was made in the studio of Revolución. It came under attack by the rival group, led by old communists (the Partido Socialista Popular, 1925-61) such as Edith García Buchaca (Consejo Nacional de Cultura) and Alfredo Guevara. PM was presented on a television channel controlled by the Lunes group during the Spring of 1961, and then was banned.

“Words to Intellectuals” is a typical Fidel Castro speech: long and repetitive, it makes effective use of anaphoras (repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of successive clauses) and perorations (“fear the judges of posterity! Fear the future generations, which in the end will have the last word!”). Castro constantly answers his own questions, making dialogue superfluous.

At first the speech features a faux nonchalant tone, which helps to anchor the hint that the speaker will talk for as long as he deems necessary. The points are not made directly and clearly, but by salvos of words and formulas that gradually draw the contours of what is being expressed. Fidel may be a good speaker, but his speeches are humourless and monotonous strings of mots d’ordre. They leave no doubt about who is in charge, while often obfuscating the policy implications of what is being said.

“Unless we are mistaken,” Fidel Castro said in one of his opening comments, “the basic problem hovering in the background of the atmosphere here was the problem of freedom for artistic creation.” He went on to say, “This matter has been brought up more than once by various writers visiting our country” (he mentioned Jean-Paul Sartre and C. Wright Mills). This may have suggested that the source of concerns is to be found abroad rather than in Cuba.

The claim made next is incongruous. Essentially, Castro suggests that true revolutionaries cannot reasonably have doubts or concerns about their own freedom under the “revolution” (i.e. under his regime). The revolution is also a cultural revolution, and everybody should happily participate in it.

As Fidel Castro repeats incessantly in his speech, using slightly different words, the revolutionary path is the way of the present and the future, the only legitimate way. The revolutionary “puts something above all other issues; the revolutionary puts something above even his own creative spirit: he puts the Revolution above all else and the most revolutionary artist would be the one who is willing to sacrifice even his own artistic vocation for the Revolution.” To be revolutionary “is also an attitude towards life, being revolutionary is also an attitude to the existing reality, and there are men who are resigned to that reality, there are men who adapt to that reality and there are men who can not resign themselves or adapt to that reality and they try to change it, that’s why they are revolutionaries.” To those who are “resigned,” or for whom artistic creativity is important in and of itself, for those individuals, concludes Castro, “the Revolution can be a problem.” Are they a problem for the revolution? Without saying that explicitly, the door is clearly open for this interpretation:

We the people must think first about ourselves; that is the only attitude that can be defined as a truly revolutionary attitude. And for those who cannot have or do not have that attitude, but who are honest people, it is for whom exists the problem to which we referred, and just as the Revolution constitutes a problem for them, they also constitute a problem for the Revolution, a problem that the Revolution must worry about.

The revolutionaries, for Castro, are “the vanguard of the people.” The rest are either followers, individuals who may be “honorable” though not revolutionaries, or plain counter-revolutionaries. As he states in the most famous passage of this speech, the latter have no rights:

The Revolution must only repudiate those who are incorrigibly reactionary, who are incorrigibly counterrevolutionary. Because the Revolution understands the interests of the people, since the Revolution signifies the interests of the entire Nation, no one can rightly claim a right against it. I think this is very clear. This means that within the Revolution, everything; against the Revolution, nothing. Against the Revolution nothing, because the Revolution also has its rights and the first right of the Revolution is the right to exist and nobody can be against the right of the Revolution to exist. There wouldn’t be an exception in the law for artists and writers. This is a general principle for all citizens.

What is never clear is the status of those who do have doubts and concerns and who therefore are not true revolutionaries. He says that they are not necessarily counterrevolutionaries though, a nuance always emphasized by observers who want to present this speech as evidence of his tolerance. Castro talked about “doubt” that “remains for writers and artists who, without being counterrevolutionaries, do not feel revolutionary either.” But he is not articulating a pluralist perspective, in which both revolutionaries and non-revolutionaries could have similar rights and could be equally welcomed in the new Cuba.

British scholar Antony Kapcia suggests that a misunderstanding can derive from a poor translation from the Spanish. He says that “contra” means “against” rather than “outside” (I have seen both translations by reputable scholars). The difference is fundamental for him:

For his statement indicated not ‘if you are not with us, you are against us’ (which the use of fuera would have meant) but the more inclusive ‘if you are not against us, you are with us.’ This is not mere semantics, for one characteristic of the Revolution’s processes subsequently has, indeed, been its ‘argumentalism’ [. . .], its willingness to allow and even encourage internal debate, within clear parameters and behind metaphorically closed doors. . . (my emphasis)

For Kapcia, “exclusion and a ‘hard line’ have tended to be applied only to those publicly going beyond those ‘doors’ and those parameters.” Here Kapcia is disingenuous, for as he should know, there was never a clear line between in and out, between “not being with us” and “being against us.” How did PM become “against us” and not merely “not with us” for instance? What “internal debate” was encouraged when Fidel Castro delivered his speech, with his pistol on the table? Many, perhaps most cases of censorship in Cuba victimized individuals who were not opposed to the regime, who could not straightforwardly be called “counter-revolutionaries,” and who often could not understand why their work was being censured, or even how it is censured: the moment or the place is not appropriate, maybe somewhere else or later, and so on.

Although there has never been any doubt about who was in charge in Cuba under Fidel Castro (a Cuban artist once told me it was an absolute monarchy), the chains of command within the government apparatus and within the cultural field are made of many levels of authority, where negotiations and competitions do take place between individuals, and where opportunities to interpret “the substance” of Fidel Castro’s thought are real, all of which create an additional layer of uncertainty to the “Against the Revolution nothing” mot d’ordre. One has rights unless one doesn’t, one can speak one’s mind unless one can’t, one doesn’t have to be a revolutionary but since not being a revolutionary is not clearly differentiated from being a counter-revolutionary, the best strategy for survival and recognition as artist cannot be clearer: follow the leader/La Revolución.

There are additional fascinating passages in this speech. About the state’s role in culture, Castro says: “It is a duty of the Revolution and of the Revolutionary Government to feature a highly qualified entity that stimulates, encourages, develops and provide orientation, yes, provide orientation to the creative spirit.” He defends the embattled National Council for Culture (CNC) in the wake of the PM censorship scandal, comparing its role to other state agencies, including the police, to prove that its existence is normal and necessary, then he makes the only joke of the speech (if this was a joke) about how the CNC, like the state, could one day disappear, in an early reference to Marxist-Leninist theory on the withering away of the state under communism:

The existence of an authority in the cultural order does not mean that there is a reason to worry about the abuse of that authority, because wouldn’t we want or desire that cultural authority to exist? In the same way, one could wish that the Militia did not exist, or the Police did not exist, that the Power of the State did not exist, or even that the State did not exist, and if someone is so concerned about the existence of even the most minimal state authority, in that case, don’t worry, have patience, for one day will arrive when the State will cease to exist altogether. (APPLAUSE)

After admitting he didn’t even see PM, he focuses on the only important question for him:

one could have a discussion on whether or not the decision was just or fair. But there is something that nobody call into question and that is the right of the Government to exercise that function, because if we challenge that right, it would mean that the Government does not have right to review the films that are going to be presented to the people (my emphasis).

In other words, this is not primarily an aesthetic or even ideological question: what is at stake is power.

Though Fidel Castro is not explicitly subscribing to socialist realism, and one can dig out two or three quotes from him or Che Guevara that suggest a certain openness to a more open conception of the arts, he clearly advocated an art that is political, revolutionary, “constructive”, and “optimistic” (“A pessimist could never be a revolutionary”), very much like socialist realism. Daura Olema García’s novel Maestra voluntaria, for instance, fits the bill perfectly and was given an award by the UNEAC as early as 1962.

The speech ends on a crescendo on how revolution is “the most important event of the century for Latin America,” and how it will fight and defeat cultural deprivation (“We will wage a war against cultural deprivation. We are going to unleash an colossal struggle against cultural deprivation. . . ”), how it is already accomplishing so many great things that indeed, how could anyone refuse to embrace it, or worse: how could one consider leaving the country? In fact,

. . . those who are not capable of understanding these things, those who let themselves be deceived, those who allow themselves to be confused, those who allow themselves to be confused by lies, are those who abandon the Revolution. What about those who have abandonned it, and what shall we think about them, other than with sorrow? To leave this country, a country in full revolutionary effervescence, and to seek refuge in the entrails of the Imperialist Monster, where no manifestation of the spirit can survive? And they have abandoned the Revolution to go there. They have preferred to be fugitives and deserters from their homeland than to be even only spectators. And you have the opportunity to be more than spectators, to be actors of that Revolution, to write about it, to express yourself about it.

No wonder many who were present concluded that for Fidel Castro, if one is not one hundred percent with him/the revolution, chosing instead to be “fearful, self-centered, destructive and pessimistic,” as Par Kumaraswami summarized, then one cannot be too far from “objectively” being a traitor, a diversionist, a deviationist, or more plainly, a counterrevolutionary.

Echo of Mao’s Talks at the Yan’an Forum

“Words to Intellectuals” is remarkably similar to Mao’s Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art (1942), which Fidel Castro mentions at the beginning of his speech in a puzzling statement:

I must confess that in a sense these issues caught us a little unprepared. We did not have our Yenan conference with Cuban artists and writers during the Revolution. Actually, this is a revolution that was born and came to power in a time, it can be said ‘record.’ Unlike other revolutions, it did not have all the main problems solved.

Leaving aside the strange idea that revolutionaries usually find solutions to pressing problems before they seize power, it is notable that Fidel Castro knew about Mao’s speech of 1942 and conceivably found inspiration in it. Like “Words to Intellectuals,” Mao’s series of “talks” were prompted by concerns among artists regarding the revolutionary movement and its implications for art and the role of intellectuals in China. The “Talks” became a foundational statement for the cultural policy in China for decades. Both Fidel Castro and Mao urge artists to subordinate individual or purely artistic concerns to the promotion of collective interest of the “working people” (Mao) or the “revolution” (Fidel Castro). Mao’s rhetoric is more explicitly Marxist: he talks to his “comrades” about the “petty-bourgeoisie” and the “proletariat.” Fidel Castro talks like a proto-Marxist and a Latin American populist about the “people” led by “revolutionaries.” In fact, most of the time he skips the “people” altogether and just talks about the Revolution, subject and object of the historical moment. Both Mao and Fidel Castro present art and literature as important—they talk about the need for a “cultural army” (Mao) and a “cultural revolution” (Fidel Castro)—but subordinate to “politics” and the revolution. For Mao,

In our struggle for the liberation of the Chinese people there are various fronts, among which there are the fronts of the pen and of the gun, the cultural and the military fronts. To defeat the enemy, we must rely primarily on the army with guns. But this army alone is not enough; we must also have a cultural army, which is absolutely indispensable for uniting our own ranks and defeating the enemy.

Or again:

Literature and art are subordinate to politics, but in their turn exert a great influence on politics. Revolutionary literature and art are part of the whole revolutionary cause, they are cogs and wheels in it, and though in comparison with certain other and more important parts they may be less significant and less urgent and may occupy a secondary position, nevertheless, they are indispensable cogs and wheels in the whole machine, an indispensable part of the entire revolutionary cause.

Their position toward non-revolutionary artists is similar. Mao said:

The petty-bourgeois writers and artists constitute an important force among the forces of the united front in literary and art circles in China. There are many shortcomings in both their thinking and their works, but, comparatively speaking, they are inclined towards the revolution and are close to the working people. Therefore, it is an especially important task to help them overcome their shortcomings and to win them over to the front which serves the working people.

As was mentioned above, a priori Fidel Castro does not require—read: La Revolución does not require–artists and writers to be “revolutionaries.” Petty-bourgeois and non-revolutionaries, with their misplaced self-interest and concerns, can be reeducated, if they are not “incorrigibly counter-revolutionaries.” “As long as they do not persist in their errors,” offered Mao, “we should not dwell on their negative side and consequently make the mistake of ridiculing them or, worse still, of being hostile to them.” History proves that neither Fidel nor Mao were very patient with those crooked timbers of humanity, when they failed to shed whatever prevented them from becoming total servants of the new state.

Last but not least, both Mao and Fidel Castro denied they were against freedom in art or in public expression, and at the same time affirmed that artists are not free to express views that are contrary to the policies they defend. For Mao:

We want no sectarianism in our literary and art criticism and, subject to the general principle of unity for resistance to Japan, we should tolerate literary and art works with a variety of political attitudes. But at the same time, in our criticism we must adhere firmly to principles and severely criticize and repudiate all works of literature and art expressing views in opposition to the nation, to science, to the masses and to the Communist Party, because these so-called works of literature and art proceed from the motive and produce the effect of undermining unity for resistance to Japan.

And again:

In literary and art criticism there are two criteria, the political and the artistic. According to the political criterion, everything is good that is helpful to unity and resistance to Japan, that encourages the masses to be of one heart and one mind, that opposes retrogression and promotes progress; on the other hand, everything is bad that is detrimental to unity and resistance to Japan, foments dissension and discord among the masses and opposes progress and drags people back.

In other words: Within the revolution, meaning in support of the revolutionary avant-garde, everything is allowed, in fact it is encouraged; against the revolution, a category that could include not being “helpful” to the cause, nothing is allowed.

Almost half a century after the “Words to Intellectuals,” a man considered as a critical intellectual in Cuba, cultural critic Desidero Navarro, asked the following questions during a conference on cultural policy in Cuba sponsored by the Casa de las Américas:

Today, the cultural and social life of the country has once again put on the table many more concrete questions that, even after ‘Words to the intellectuals’, were left without a broad, clear and categorical answer: What phenomena and processes of Cuban cultural and social reality are part of the Revolution and which are not? How to distinguish which cultural work or behavior acts against the Revolution, which in favor and which simply does not affect it? What social criticism is revolutionary and which is counterrevolutionary? Who, how and according to which criteria, decides the correct answer to these questions?

These would have been timely questions in 1961; they are strikingly naive and possibly disingenuous in 2007. The idea defended in Cuba and sometimes abroad that the Cuban cultural policy grounded in the 1961 speech guaranteed full freedom of artistic expression to all but open enemies of the revolution only makes sense if one accept as self-evident that homosexuals, fans of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, Catholics, Jehovah Witnesses, filmmakers who produce documentaries on Cubans drinking and dancing in bars of Havana, young people with long hair, and even cultural ambassadors of the regime like Pablo Milanés (who ended up in labor camp in the 1960s), are or were unmistakenly “open enemies of the revolution.” To repeat, this kind of interpretation, defended by the regime and many academics, prevents one from understanding how so many individuals who were silenced sincerely thought of themselves as “revolutionaries” and were stunned and outraged to be accused of ideological diversionism, improper conduct, or counterrevolutionary activities. While there is no doubt that supporting a return of Batista and his regime (which basically nobody did) would instantly turn one into an “open enemy of the revolution,” it is no less clear that criticizing the Fidel Castro and his policies, even in the name of the revolution, would result in the same effect.

Modern Dictatorship and the Question of Freedom

Modern dictatorships are never against freedom per se; they are against freedom to disagree with the political leadership, and by extension, to disagree with the “people.” Heads of state and people are one and the same. French proto-totalitarian revolutionary Saint Just put it succinctly: “No freedom for the enemies of freedom!”

The idea is simple: one creates a “within” that represents a legitimate space for public expression, and an “outside” for actions and thoughts deemed illegitimate.

In a speech delivered in 1935, Benito Mussolini famously said “everything is in the State, and nothing human or spiritual exists, much less has value, outside the State. On August 3rd, 1968, Leonid Brezhnev said “Each Communist party is free to apply the principles of Marxism-Leninism and socialism in its own country, but it is not free to deviate from these principles if it is to remain a Communist Party.”

Radical socialism and communism in particular always had a problem with freedom because unlike democracy, it is an end, not a mean, and one cannot build socialism if everybody is free to oppose socialism. Even in the “Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art” (1938) signed by André Breton and Diego Rivera (but written by Leon Trotsky and Breton), a text often considered as the proof that free art is compatible with Marxism and revolution, the call for “complete freedom in art” is defused by the caveat that “the revolutionary state has the right to defend itself against the counterattack of the bourgeoisie, even when this drapes itself in the flag of science or art.” After all, the “supreme task of art in our epoch is to take part actively and consciously in the preparation of the revolution.” Same idea: you are free to follow me, you are not free not to.

For a revolution to truly respect civil and political liberties, it first needs to come to an end, and be replaced by the rule of law, democratic institutions, civil and political liberties, as well as free and fair elections. The Cuban revolution ended long time ago (early 1960s in my view), and the rhetoric about the open-ended revolution and its “right to exist” is the fig leaf masking the ongoing repression of the democratic rights, including artistic freedom. In a democracy, the government speaks to intellectuals, not at them. And not with a pistol on the table.

- This text is an adaptation of an except from my book Culture and the Cuban State, Participation, Recognition, and Dissonance under Communism (Lexington, 2017).

-

Antony Kapcia, Havana, The Making of Cuban Culture (Oxford and New York: Berg, 2005), 134.

-

Desiderio Navarro, “¿Cuántos años de qué color? Para una introducción al Ciclo,” in Centro Teórico Cultural (2008), La política cultural del período revolucionario: Memoria y reflexión, Ciclo de conferencias organizado por el Centro Teórico-Cultural Criterios, Primera Parte (Havana: Centro Teórico-Cultural), 19.

-

See Yvon Grenier “¿Cuándo terminó la Revolución Cubana? Una Discusión.” With Jorge Domínguez, Julio César Guanche, Jennifer Lambe, Carmelo Mesa-Lago, Silvia Pedraza, and Rafael Rojas, Cuban Studies vol. 47 (2019) 143-165; and Yvon Grenier, “Cuban Studies and The Siren Song of La Revolución,” Cuban Studies 49 (2020): 310-329.

Yvon Grenier (Ph.D.) is Professor of Political Science at St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia, Canada. His most recent book is Culture and the Cuban State: Participation, Recognition, and Dissonance under Communism (Lexington, 2017). His Twitter is @ygrenier1

Yvon Grenier (Ph.D.) is Professor of Political Science at St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia, Canada. His most recent book is Culture and the Cuban State: Participation, Recognition, and Dissonance under Communism (Lexington, 2017). His Twitter is @ygrenier1

©Literal Publishing

Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

Posted: July 25, 2021 at 11:26 am