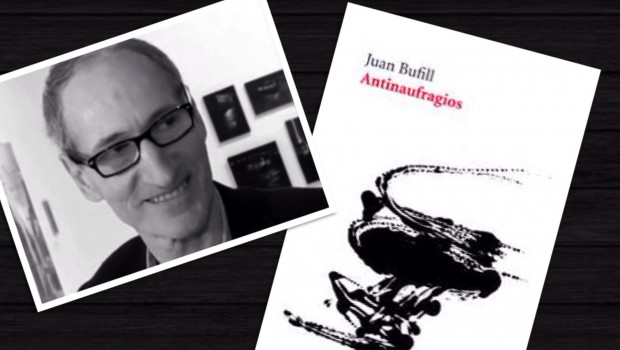

Enrique Vila-Matas: The Last Writer

El último escritor

Pedro M. Domene

Enrique Vila-Matas (Barcelona, 1948) is currently considered one of the most interesting narrative voices on the Spanish publishing scene. He is the author of a singular body of literary work, begun with two nouvelles–Mujer en el espejo contemplando el paisaje (1973) and La asesina ilustrada (1977)–both profoundly indebted to Kafkian influence. His later work synthesizes a variety of avant-garde techniques, and also provides for careful reflection upon the irony and the humor of this complex world. Historia abreviada de la literatura portátil (1985) introduced a tendency marked by postmodernism, and for Vila-Matas it meant the first of several acclaimed successes creating characters as lonely and solitary as they are ill with literature. Together, El viaje vertical (1999), Bartleby y compañía (2000), and El mal de Montano (2002) make up his most daring narrative gamble. With his latest installment, Dublinesca (2010), the reader attends the most festive funeral of the Gutenberg era.

* * *

Pedro M. Domene: If I may, I’d like to begin this interview by asking how much in your texts is fiction, and how much is autobiography?

Enrique Vila-Matas: The broad passageway that joins fiction and reality is cool and well-ventilated, and the air within blows about with the same natural ease with which I mix biography and invention.

PMD: The reason I ask is that recently there has been a lot of talk about the poet Gil de Biedma who, as you know, imbued a great deal of his work with concrete narrative elements taken from his own life.

EVM: But, I don’t exactly tell the story of my life. Rather, I create diverse characters, and I draw only on my supposedly unique identity to form and develop them (this singularity is only a presumption, of course, because in my opinion, my identity has never been ‘unique’). And I’ll tell you something else: in Dublinesca all of my characters unfold into multiple identities; they have other alter egos.

PMD: To what extent are you conscious of this willful escape from reality?

EVM: If this «willful escape» did exist, it could never be an escape from reality, because my life is also real. On the other hand, I’ve been very interested in the real world lately, ‘real’ in the classical sense. This is apparent, I think, in Dublinesca. I think realism took on the task of writing about the grayness of life, la vida gris, and it tried to carry out this task in some sort of extraordinary way. Isn’t this what Flaubert did? What Flaubert ended up saying was that a subject could be ordinary, lowly, degrading; but art would redeem it all. I believe Dublinesca takes up this same challenge when, in the process of writing the apathetic or strange epic of a retired book publisher’s daily life, I challenge myself to get at real life on the printed page.

PMD: The era of Gutenberg is ending. Are we faced with a new conception of the apocalyptic, literarily speaking?

EVM: There is no radical division between the printed and the digital word, as they would have us perceive, only continuity.

PMD: Perhaps this is why we must celebrate a festive funeral for the Gutenberg era, as you maintain in Dublinesca?

EVM: The apocalyptic can be found in all civilizations, and Riba, my character, understands that the end of the world can only be dealt with at this point by means of parody. His funeral for the Gutenberg era is a party. After all, as I have said, there is no radical division between the print and digital worlds, only continuity.

PMD: Can books, in general, resist the onslaught of modern times?

EVM: What is truly important is that language and thought are not lost. The format–whether it be Kindle, or a stone engraving, or a printed book–isn’t terribly important.

PMD: That’s why Dublinesca seems to take it one step further; here, not even the publisher puts up any resistance.

EVM: Riba, the publisher, has come to ruin because his catalogue was too demanding. Take a look at the catalogue. I had great fun making it up; for a few days I became a publisher.

PMD: Can we talk about a return to a traditional narrative framework–with a calculated sense of time, even a progressive order–that’s used to tell the story of your publisher? Or should we leave it to the reader’s imagination?

EVM: We can indeed talk about a return to a fairly orthodox narrative framework here, though it is paired with the avant-garde nature of the novel’s project. I bring together the conventional with the revolutionary, and this is the source of the possible originality of my proposal. The truth is, this is something I’ve always tried to do, but it seems that here I’m closer to achieving my goal.

PMD: In this volume, you persist in rendering homage to your favorite writers with extraordinary tributes, as you have done for years. In this case, it’s Bloomsday, Joyce, and the Irish saga.

EVM: The atmosphere in this book is that of the Irish novels. The more rainy passages of Dublinesca touch upon it. «Old age, disease, the gray climate, a silence of centuries. Boredom, rain, sheer curtains closed up to the outside world. Familiar ghosts from Aribau Street. We needn’t seek out palliative remedies to ease the pain of our parents’ drama, or of our own. Aging is disastrous.» This gray atmosphere and this boredom are there in Dublin, and in the Irish novels.

PMD: Does Dublinesca assume a celebration of the intellect with its abundant references to books and authors, as well as the constant shadow of Ulysses?

EVM: A celebration of the intellect? It’s clearly not my place to say so.

PMD: Are you concealing a story within an essay in order to compose your own intellectual autobiography?

EVM: It’s possible; I couldn’t say exactly. I try to do a great deal, and sometimes I forget about some of the things that I attempt.

PMD: With respect to time, does it really pass as fast as it says in Dublinesca?

EVM: I’m not sure. I always remember that saying by I don’t know whom, I think it was Vilém Vok: «Life is short, but the day is long.» Czech writers sometimes write as if they were Chinese, don’t you think?

PMD: Even though this novel may not presume to be an act of vindication, is there a kind of sorrow particular to the literary publisher?

EVM: This sorrow does exist; at least it does since I named it in the book. It’s a sort of droning buzz, a burdensome weight that the publisher is never able to cast off.

PMD: According to your answer, who will foresee the end of literature first, a publisher or a writer?

EVM: I am sure that one day there will come a writer who will be the last. There will be a last writer; there has to be. I see him without any publisher, and I couldn’t really say why. The last publisher will come before the last writer. The writer will be alone in the world, ultimately and without a doubt, alone. And he’ll think these kinds of things, for example: «The creative work belongs to the author.»

PMD: Another of Dublinesca’s interesting elements, if you’ll allow the reference, is the metaphor of the voyage, and above all, the visit of the Knights of the Order of Finnegans. What must one do to join this Order?

EVM: It is a republican order; at the moment it has yet to admit women (we are unjustly labeled as sexist). There are six knights, and on each Bloomsday we name one more, admitted so long as he is accepted by a minimum of five of the six members. The candidate is nominated by someone within the Order, by email. We study the proposal and accept or disapprove the nomination. It is an indispensable requirement that the candidate adore Joyce. It is our intent to be the successors of the Order of Toledo, founded by Buñuel and Pepín Bello. The gentlemen of the order are almost all writers: they are Eduardo Lago, José Antonio Garriga Vela, Antonio Soler, and Jordi Soler. There is also a publisher, Malcom Otero Barral. This year, Andreu Jaume will be joining us. He is a publisher with Lumen, and he’s pro-British. Because the rest of us feel ourselves to be quite Irish, I imagine we’ll have a somewhat difficult time with this new Knight, but we’ll try to make an Irishman out of him.

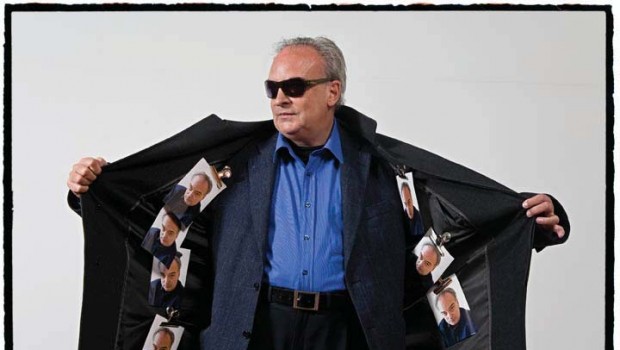

PMD: How does it feel to go around with that red badge on your jacket lapel, as if you were a knight of the Légion d’Honneur?

EVM: I walked into an Irish pub the other day, and the barman was French, and when he saw the red insignia he became excited, believing he found himself in the company of a distinguished fellow countryman. He wanted to know what heroism had earned me such a distinction, and when I told him I was a writer from Barcelona, his face went blank, and he became visibly disappointed. Even so, he agreed to bring our food to the table, something unusual in a pub where that kind of thing isn’t the norm.

PMD: What have you inherited from the old Vila- Matas, I mean the author previous to Exploradores del abismo (2007)?

EVM: I am his executor. I manage his work. I maintain the friendships that he had. I’ve advised him upon relocating to another neighborhood and a new house. I’ve also given him advice on changing his character, and now he’s more pleasant. I manage his life sensibly.

PMD: What might Vila-Matas really make the most of in this life?

EVM: What do I like? Almost everything. To begin with, life.

PMD: As a parting question, at this moment in your literary life, what could it mean for you to be able somehow to fictionalize the self in convincing literary terms?

EVM: I don’t know; I haven’t thought at all about this issue. I know that I am convincing when I fictionalize my own self, and that’s all.

PMD: Who will travel with you on the next Bloomsday?

EVM:I’ll meet up with the Knights of the Order in Dublin. At ten minutes to six on the sixteenth of June, we’ll climb the Martello Tower, and we don’t allow anyone outside of our society to be present for the ceremony of acceptance for the newly ‘ordained’ member (the word we use is ‘recipient’ instead of ‘ordained,’ which also means ‘orderly’ in Spanish, and as such is subject to misunderstandings). At exactly six o’clock, we’ll leave the tower and mingle with the rest of the world. I like to climb the tower, because from there I can see the Irish Sea. That sea lifts my spirits.

Enrique Vila-Matas (Barcelona, 1948) está considerado actualmente como una de las voces narrativas más interesantes del panorama editorial español. Autor de una obra literaria singular, que inició con dos nouvelles de profunda raigambre kafkiana, Mujer en el espejo contemplando el paisaje (1973) y La asesina ilustrada (1977). Su obra posterior sintetiza las más variadas técnicas vanguardistas, además de ofrecer una meditada observación sobre el humor y la ironía de este complejo mundo: Historia abreviada de la literatura portátil (1985) marcó una línea tildada de posmoderna y supuso, para Vila- Matas, el inicio de sonados éxitos inventando personajes tan solitarios como enfermos de literatura. El viaje vertical (1999), Bartleby y compañía (2000) y El mal de Montano (2002), conforman su apuesta narrativa más arriesgada. Con su última entrega, Dublinesca (2010), el lector asiste al funeral más festivo de la era Gutenberg.

* * *

Pedro M. Domene: Permítame que inicie esta entrevista preguntándole, ¿cuánto de ficción y cuánto de autobiografía contienen sus textos?

Enrique Vila-Matas: El amplio corredor que une ficción y realidad es fresco y muy ventilado y el aire corre ahí con la misma naturalidad con la que mezclo biografía e invención.

PMD: Se lo pregunto porque, últimamente, se habla mucho del poeta Gil de Biedma que, como usted sabe, hizo de su vida el sólido argumento de buena parte de su obra.

EVM: Pero yo no cuento exactamente mi vida. Más bien creo personajes múltiples, y los construyo a todos valiéndome tan solo de una supuesta única identidad mía (sólo supuesta, claro, porque en mi opinión no ha sido nunca única). Y le diré más: En Dublinesca, por ejemplo, todos mis personajes se desdoblan, tienen otros alter egos.

PMD: ¿Hasta qué punto es consciente de esa voluntariosa huida de la realidad?

EVM: De existir una «voluntariosa huida» esta nunca podría ser una huida de la realidad porque mi vida también es real. Por otra parte, estoy muy interesado últimamente en el mundo –en el sentido clásico– de lo real. En Dublinesca creo que se nota. Pienso que el realismo aceptó la tarea de escribir sobre la vida gris y trató de cumplir con ella de algún modo extraordinario. ¿No es lo que hizo Flaubert? Lo que vino a decir Flaubert fue que el tema podía ser corriente, bajo, degradante, pero el arte lo redimiría todo. Creo que ese desafío está en Dublinesca, donde, al escribir sobre la apática o extraña epopeya de la vida cotidiana de un editor retirado, me planteo el reto de alcanzar la vida real en el papel.

PMD: Acaba la era Gutenberg, ¿estamos ante un nuevo concepto apocalíptico, literariamente hablando?

EVM: No hay entre la imprenta y lo digital un corte radical como nos quieren hacer ver, sino una continuidad.

PMD: ¿Quizá por eso haya que celebrar un funeral festivo por la era Gutenberg, como afirma usted en Dublinesca?

EVM: Lo apocalíptico está en todas las civilizaciones y Riba, mi personaje, entiende que el fin del mundo sólo puede ser ya tratado de forma paródica. Su funeral por la era Gutenberg es una fiesta. Después de todo, como le he dicho, no hay entre la imprenta y lo digital un corte radical sino una continuidad.

PMD: El libro, en general, ¿resiste el embate de los tiempos modernos?

EVM: Lo que importa verdaderamente es que no se pierda el lenguaje y el pensamiento. El formato –si es Kindle o un grabado sobre una piedra o un libro impreso– no importa demasiado.

PMD: Por eso Dublinesca parece una vuelta de tuerca, no resiste ni siquiera el editor.

EVM: Riba, el editor, se ha arruinado porque su catálogo era muy exigente. Véase el catálogo –me divertí mucho haciéndolo– que se encuentra en el libro. Por unos días, me convertí en editor.

PMD: ¿Podemos hablar de una vuelta a un esquema narrativo tradicional, con un tiempo calculado, incluso un orden progresivo, para contar la situación del editor Samuel Riba, o dejamos al lector que imagine?

EVM: Se puede hablar, en efecto, de esa vuelta a un esquema narrativo bastante ortodoxo, aunque mezclado con el vanguardismo de la propuesta. Unifico lo convencional con lo revolucionario. De ahí la posible originalidad de mi propuesta. De hecho, lo he intentado siempre, pero ahora parece que me acerco más a lograr mis objetivos.

PMD: En esta entrega usted insiste en esos homenajes particulares que, desde hace años, viene tributando a sus escritores favoritos. En este caso, al Bloomsday y a Joyce, así como a la saga irish.

EVM: La atmósfera del libro es la atmósfera de las novelas irlandesas. Se habla de ello en algunas de las páginas más lluviosas de Dublinesca. «Vejez, enfermedad, clima gris, silencio de siglos. Aburrimiento, lluvia, visillos que aíslan del exterior. Fantasmas tan familiares de la calle Aribau. No hay que buscarle paliativos al drama de sus padres y al suyo propio, envejecer es un desastre». Ese clima gris y ese aburrimiento están en Dublín y en las novelas irlandesas.

PMD: Como en casos anteriores, ¿supone Dublinesca una fiesta a la inteligencia por sus abundantes referencias a libros y autores, además de la sombra permanente del Ulysses?

EVM: ¿Una fiesta a la inteligencia? Es evidente que no me corresponde a mí decirlo.

PMD: ¿Disfraza usted un relato bajo la sombra de un ensayo para construir su propia autobiografía intelectual?

EVM: Es posible, no sabría decirle con exactitud. Intento hacer muchas cosas y a veces me olvido de algunas de las que intento.

PMD: Con respecto al tiempo, ¿es verdad que pasa tan rápido como dice en Dublinesca?

EVM: No estoy seguro. Siempre recuerdo aquella frase de no sé quién, creo que es de Vilém Vok: «La vida es breve, pero el día es largo». Los escritores checos a veces escriben como si fueran chinos, ¿no le parece?

PMD: Aunque esta novela no suponga una revancha, ¿existe la pena del editor?

EVM: Esa pena existe, al menos desde que la he nombrado en el libro. Es una especie de zumbido, de lastre del que no logra desprenderse nunca el editor.

PMD: Según su respuesta, quién prevé el fin de la literatura antes, ¿un editor a un escritor?

EVM: Estoy seguro de que un día –lejano o no– habrá un escritor que será el último. Habrá un último escritor, tiene que haberlo. Lo veo sin editor y no sabría decirle ahora bien por qué. El último editor será anterior al último escritor. El escritor estará solo en el mundo, definitivamente solo. Y pensará cosas como ésta por ejemplo: «La obra es del autor».

PMD: Otro de los aspectos interesantes de Dublinesca, si me permite, es la metáfora del viaje y, sobre todo, la visita de los Caballeros de la Orden del Finnegans, ¿qué hay que hacer para formar parte de esta Orden?

EVM: Es una Orden republicana, no ha admitido mujeres por ahora (nos califican injustamente de machistas), la componemos seis caballeros y en cada Bloomsday nombramos a uno nuevo, que entra si tiene la aceptación de, como mínimo, 5 de los 6 miembros. El candidato es propuesto por alguien de la Orden, a través de un e-mail. se estudia la propuesta y se aprueba o se desaprueba. Es condición indispensable adorar a Joyce. Tratamos de ser los sucesores de la Orden de Toledo que fundó Buñuel con Pepín Bello. Los caballeros son casi todos escritores. Son Eduardo Lago, José Antonio Garriga Vela, Antonio Soler y Jordi Soler. También hay un editor, Malcolm Otero Barral. Este año entra Andreu Jaume, editor de Lumen y probritánico. Como los demás nos sentimos irlandeses, creo que vamos a pasarlo algo mal con este nuevo Caballero, pero vamos a tratar de irlandizarlo.

PMD: ¿Qué se siente luciendo en el ojal de su americana el botón rojo que lo acredita poseedor de la Légion d´ Honneur?

EVM: Entré en un pub irlandés el otro día y el camarero era francés y al ver el signo rojo se emocionó creyendo que se encontraba con un compatriota insigne. Quiso saber qué heroicidad era la que me había llevado a esa distinción y cuando le dije que era barcelonés y escritor se le mudó el rostro, quedó vivamente decepcionado. Aún así, aceptó llevarnos la comida a la mesa, algo insólito en un pub en el que no se estila eso.

PMD: ¿Qué ha heredado usted del Vila-Matas de antes, me refiero al autor previo a Exploradores del abismo (2007)?

EVM: Soy su albacea. Administro la obra. Conservo las amistades que él tenía. Le he aconsejado en su cambio de barrio y de casa. Le he aconsejado también en su cambio de carácter y ahora es más afable. Administro sensatamente su vida.

PMD: ¿De qué se aprovecharía realmente Vila-Matas en esta vida?

EVM: ¿Qué me gusta? Casi todo. Para empezar, la vida.

PMD: Para terminar, en este momento de su vida literaria, ¿qué puede significar para usted esa posibilidad de ficcionalizar, de alguna manera, el yo en términos literarios convincentes?

EVM: No lo sé, no tengo nada pensada esta cuestión. Sé que soy convincente al ficcionalizar mi yo, y eso es todo.

PMD: ¿Quién viajará con usted en el próximo Bloomsday?

EVM: Me encontraré en Dublín con los Caballeros de la Orden. A las 6 menos diez del 16 de junio subimos a la Torre Martello y prohibimos que para la ceremonia de aceptación del nuevo ordenado –la palabra que utilizamos es recipiente en lugar de ordenado, que se presta a equívocos– haya alguien ajeno a nuestra sociedad. A las seis en punto salimos de allí y nos mezclamos con el mundo. A mí me gusta subir a la torre porque desde allí veo el mar de Irlanda. Ese mar me entusiasma.