Everything is Political, Including Poetry

Todo es político, incluso la poesía. Entrevista a Margaret Randall

Yasmín Rojas

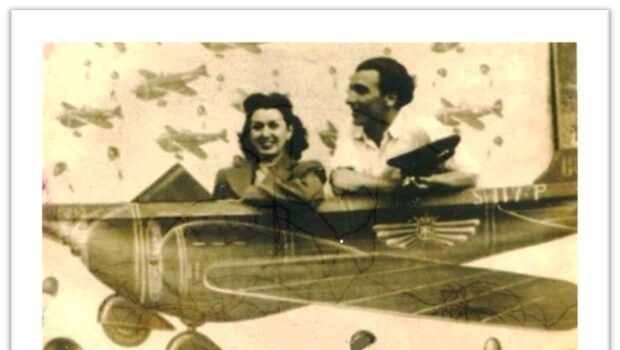

On April 26th, 2018, in San Jerónimo Lídice, Mexico City, a very special event took place in “El Bodegón de San Jerónimo”, owned by chef Ximena Mondragón Randall, daughter of the poets and editors of El Corno Emplumado / The Plumed Horn, a 1960s bilingual literary magazine that functioned as a bridge between north American writers and Latin-American writers. Among the many published and translated in its pages were Octavio Paz, José Emilio Pacheco, Roque Dalton, Alejandra Pizarnik, Allen Ginsberg, T.S. Eliot and many more. During the event, while Margaret read “recipe / poems” from her book Hunger’s Table. Women, Food and Politics, Ximena Mondragón Randall prepared her delicious food based on the poems her mother was reading in English and that, María Vasquez Valdés, translated into Spanish. It was definitely an enriching experience, that I was able to enjoy thanks to Margaret Randall’s invitation, who after a most delicious dinner, granted me an interview with sufficient nutritious information about her life, her activism and her years as editor of the 1960s cosmopolitan magazine: El Corno Emplumado.

YR. How did your relationship with the Spanish language begin? Was it through your mother who was a literary translator?

MR. I was born in New York, my family is from New York and when I was ten years old, my parents traveled all around the country because they were not happy in that city. They wanted to see where we could live and they chose New Mexico. Even though Spanish is spoken there, I did not learn there until I traveled to Spain by myself as an adult in the year 56. I lived in Sevilla and began learning Spanish. My mother learned Spanish in New Mexico at the University. We did not have any roots with Spanish in the family.

YR. Why did you decide to come and live in Mexico City?

MR. I had my first son in New York in the year 1960. I was a single mother. Back then it was hard being a single mother. In NY, there weren’t many good conditions, I mean, there were not many nursery schools or things like that. I worked a lot and did not see my son very much. Then, in the year 61, I do not know why, it occurred to me that if we moved to Mexico, maybe I could spend more time with my son. It is one of those things that I cannot explain myself very much, but it worked out.

YR. Could you tell me a bit about the cultural atmosphere of the 1960s, when El Corno Emplumado / The Plumed Horn was being published?

MR. The time in which El Corno Emplumado had its eight-year run was culturally powerful in many different ways, in the arts, in politics, in cross-border relations. In Mexico, some of the great artists had just recently died (Diego Rivera, Tina Modotti, etc.), and their spirits and work still permeated the atmosphere. Others were still alive (David Alfaro Siqueiros, Anita Brenner, Rufino Tamayo). Mexico’s policy of giving refuge to artists who were being persecuted in other places brought refugees such as Leonora Carrington, León Felipe and Mathias Goeritz. Younger artists, such as Elena Poniatowska, Carlos Monsivais, Juan Martínez, Juan Bañuelos, Felipe Ehrenberg, and José Luis Cuevas were also appearing on the scene. In the United States, we had recently emerged from McCarthyism, and just beginning to search for voices that had been silenced during the previous decade. Throughout the Continent —I would say throughout the world— the 1960s was a time of cultural effervescence, rebellion, and resistance to social suffocation and hypocrisy.

YR. When putting together El Corno Emplumado, what other magazines did you use as models for your magazine’s content and form?

MR. Although El Corno Emplumado was one of a number of literary magazines to emerge in the early 1960s, I don’t believe we used any other journal as a model for its content and form. We wanted to be original. We saw form and content as intimately linked. We talked about creating a journal whose pages conformed to the work we printed, rather than forcing the work to conform to the pages, this is why we sometimes printed long-lined poems sideways on the page. We wanted to be modern, unique, free.

YR. The editors notes where written by yourself and Sergio, or where you in charge of the notes in English and Sergio de notes in Spanish?

MR. At the beginning Sergio wrote the editor’s notes in Spanish and I wrote the ones in English, although we sometimes translated a note that one of us would write and produced it bilingually. Later, when we began to differ in our concepts of what the magazine should be, our editor’s notes also began to differ.

YR. Sometimes you published authors that did not send collaborations but they appeared in the magazine. What was the intention of this? What did you base off of to choose the collaborations?

MR. We always searched for work by those we admired, poets and artists whose work we wanted to showcase. As we gained a reputation, more and more writers searched us out, sending us their work spontaneously. So, I would say it was a mix: if we knew that a particular poet was writing something that excited us we would ask if we could use it in the journal. But we also received many wonderful uninvited submissions, and we published many of these.

YR. Where you interested in political poetry when you began publishing the magazine or did your interest begin there and continue to evolve?

MR. I personally was not very acquainted with political poetry when I began editing El Corno Emplumado, because I came from the United States where McCarthyism had put a definite damper on anything political. I read my first great political poems after coming to Mexico. With the years, though, I have come to dislike the term “political poetry,” and I do not call myself a political poet. I believe that poetry can be about anything: a social issue, an idea, love, fear, landscape, etc. etc. In the larger sense, everything is political.

YR. Could you tell me about the aesthetic intentions that you and Mondragon shared?

MR. We shared an interest in the new, the experimental, the truthful and dynamic.

YR. The illustrations that were published in the magazine were not related to the texts, why this decision? That is, what was the graphic’s function?

MR. We did not see visual art as necessarily illustrating the written word, nor vice-versa. We felt that each creative work should stand on its own merits. Sometimes, however, such as in the issue in which we featured a section of indigenous poetry, we accompanied those texts with drawings done by Indigenous artists from the state of Guerrero. Generally, though, each contribution to the magazine was meant to be complete on its own terms.

YR. In El Corno Emplumado you published poetic anthologies. Why didn’t you publish prose anthologies?

MR. We always considered El Corno Emplumado primarily a poetry magazine. Since we mostly had contact with poets, it was easy for us to obtain small anthologies of poems from different countries. But I think that if we had received a prose anthology that we liked, we certainly would have considered publishing it. Limitation of space may also have entered into this decision.

YR. In February of 1964, the “Primer Encuentro de Poetas Americanos” in Mexico City took place, during those reunions you decided to publish a new magazine, Nueva Solidaridad, where more American poetry would be translated, even from and into Portuguese, however I have not been able to find this journal, was it ever published?

MR. No. It was our intention to publish Nueva Solidaridad, and to expand, to include other languages of the Americas, but we were never able to do so. I think Miguel Grinberg, in Buenos Aires, may have produced one issue of such a magazine but, in any case, it did not prosper.

YR. Towards the last of El Corno Emplumado’s editorials (numbers 27 and beyond), more interviews, essays, summaries and references of Cuba and the revolution where being published and less poetry was included, why these changes?

MR. In January of 1967, Sergio and I were invited to the “Encuentro con Rubén Darío”, a gathering of poets celebrating the 100th anniversary of the great Nicaraguan modernist. This event was in Cuba and hosted by Casa de las Américas in Havana. It marked our first trip to revolutionary Cuba. There we met many young poets, writers and visual artists. This is how our contact with Cuban writing and art began. I returned a year later (January 1968) to attend the Cultural Congress of Havana, where I continued to explore the Revolution and meet more writers and artists. El Corno Emplumado was being distributed all over the world by this time, but principally in the United States and Mexico. In the United States there was a resounding silence with regard to anything that was happening in Cuba. We published Cuban work because we liked it, but also because we felt it was important for U.S. readers to have access to what was going on in that country.

YR. During the years of El Corno Emplumado, what was another significant experience you have of that time? Other than being editor of the magazine.

MR. During the years of El Corno Emplumado my three daughters —Sarah, Ximena and Ana— were born. Those were certainly important moments for me. And of course the Student Movement of 1968 marked my life significantly. I am sure there were other events as well, but these are the ones I feel were most important to me personally.

YR. What would you say is the importance of El Corno Emplumado in relation to other literary magazines of the time?

MR. Back then and now, I see El Corno Emplumado’s primary importance as a bridge, a way of connecting what was going on in the southern and northern hemispheres, between creative peoples who were kept apart by political maneuvering but had a great deal to say to one another. The fact that the journal was bilingual helped a lot in this endeavor. We had ties to many other important literary and cultural projects, but I think this set us apart.

YR. What differences or similarities did El Corno Emplumado have with other magazines?

MR. Our main difference was that we were bilingual.

YR. Was the idea of intercalating illustrations with literature preconceived?

MR. We were interested in reproducing the written word and visual images, and that was the only way we could do so.

YR. What was the magazine’s reception in the US and in Latin America?

MR. El Corno Emplumado was enthusiastically received everywhere we were able to send it. This was equally true in the U.S., throughout Latin America and in many other countries as well. Although we were only able to produce 3,000 copies of each issue and send small packages of 5 or 10 to each recipient, people passed the magazine around and our readership was actually quite broad. Many libraries also had subscriptions, which enabled many more people to read it.

YR. Was the Government’s control and censorship visible? did you feel watched by any authority or political group?

MR. Yes, state censorship was real and visible during the years we published El Corno Emplumado. When we announced that our forthcoming issue would be dedicated to work from Cuba, the Pan American Union (cultural arm of the Organization of American States, OAS) threatened to cancel its 500 subscriptions if we did so. Needless to say, we did not hesitate, and we lost those valuable subscriptions. We had patronage from several branches of the Mexican government as well, the Secretary of Education, the Presidency, Bellas Artes, etc. When the journal took the side of the students in 1968, we lost those subsidies. And of course the magazine itself was forced to cease publishing as a result of our personal involvement in the Student Movement. So state control and censorship were always very clear to us.

YR. In many occasions you have regretted the fact that you did not publish more women in El Corno Emplumado, how have you tried to fix this in your later work?

MR: The lack of women in literary magazines and in publishing in general was not something that was limited to Mexico back then. It was worldwide, and continues to a great extent, even though things have improved since the 1960s. I discovered feminism while living in Mexico in 1969. It had a profound influence on my life personally and professionally. Since then I have produced many books of oral history with women, in an attempt to give voice to people who have been silenced by the patriarchy. My feminism informs all areas of my life, so logically it is present in my own poetry, and in how I live my life. I recently produced a large bilingual anthology of eight decades of Cuban poetry, Only the Road / Sólo el Camino, published by Duke University Press. Almost half of the 56 poets included are women, something very unusual for any anthology anywhere. I am always conscious of giving voice to women because we have been silenced or ignored for so long.

YR. What would you say is the importance of the writer and literature nowadays?

MR. Literature is extraordinarily important in my life and, I think, in the world. Today, when so much hate speech, so many lies, and so much so-called “fake” news have become part of the general discourse, we depend on literature to speak truth to power. To respond to the criminal in the White House who talks about walls, division, hate, we poets have to respond with the real language of life.

YR. This question has to do with Cuba and your political posture: When you heard of the “caso Padilla”, did your opinion about the “revolutionary ideal” change?

MR. No, the “Caso Padilla” did not change my opinion of the revolutionary ideal, although I think the Cuban Revolution made a mistake in making a scapegoat of Padilla and giving so much importance to the case. This was one of many incidents during a dark time of censorship which, I feel, the Cuban Revolution has moved beyond and rectified to a great extent. In highly-controlled societies there is always the danger of censorship, and one must guard against it.

YR. After living eleven years in Cuba, you moved to Nicaragua and continued supporting revolutionary groups, in what moment did you realize that you wanted to continue fighting for the rights of oppressed groups in other places of Latin America?

MR. I was long interested in social change. Participating in the Mexican Student Movement of 1968 showed me what a government is willing to do to its young people in order to “keep order.” Cuba showed me what radical social change might look like. In Cuba I met revolutionaries from other Latin American countries, and I became especially interested in Nicaragua after the Sandinistas were victorious in 1979. I am still interested in different models of social change, but at my age I no longer have the energy or desire to follow this interest so actively.

YR. When did you realize that women liberation was also important to reach a better society?

MR. As I said, I discovered feminism in 1969. When I speak about feminism I am not talking about a struggle between men and women, but a tool for the analysis of power. Since then, it has been obvious to me that real social change is not possible unless every social sector is taken into full consideration: women, people of color, the LGBQT community, those of diverse physical and mental capacities, anyone considered different from the mainstream. Too often political parties or revolutionary movements speak “on behalf” of a particular social sector. I believe it is important that each social sector speak for itself, wield real power in the struggle for change.

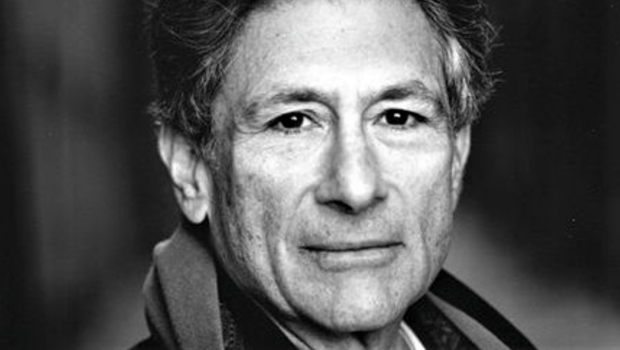

Margaret Randall continues as energetic as ever and shows this through her passionate and strong voice when reading poetry out loud. At 82 years of age, she stays active by writing poetry, visiting book fares and literature congresses around the continent. Finding equilibrium between discipline, activism and humility is a hard task but Margaret has allowed herself to do just that. It is astonishing how she still has the vitality to continue fighting against abusive powers through poetry, just like Victor Hugo and other xixth century social poets. The fact that she has managed to erase language and cultural barriers, in her life and in the life of many writers, has made her into a bridge between two cultures. The list is long; she has published and continues to publish work by poets from all over the world, whether it is poetry anthologies or whole books of her own work with their respective translations. The most recent ones are 12 poets. Anthology of new Poets from the United States and El Rizoma como un campo de huesos. This is a task that she began since her years as editor of the 31 editorials of El Corno Emplumado, magazine that continues to inspire new generations of readers.

El 26 de abril de 2018, en San Jerónimo Lídice, Ciudad de México, un evento muy peculiar se llevó a cabo en el “El Bodegón de San Jerónimo”, de la chef Ximena Mondragón Randall, hija de los poetas y editores de El Corno Emplumado/The Plumed Horn, revista literaria bilingüe, publicada en México de enero de 1962 a julio de 1969, revista ecléctica que tuvo propósitos pacifistas, inclusivos y renovadores, a partir de la poesía y su traducción al español e inglés. Durante el evento, mientras Margaret Randall leía “recetas/poemas” de su libro Hunger’s Table. Women, Food and Politics, Ximena Mondragón Randall preparaba deliciosos platillos, basados en los poemas que su madre leía en inglés, y María Vásquez Valdez traducía al español las cadencias de Randall. Definitivamente, fue una experiencia enriquecedora, que pude disfrutar gracias a la invitación de Margaret Randall, quien, después de la agradable cena, me concedió la siguiente entrevista: platicamos sobre su vida, su activismo social y su experiencia como escritora y editora de la revista literaria cosmopolita de la década de los sesenta: El Corno Emplumado.

Yasmín Rojas. ¿Cómo se inició su relación con el idioma español?

Margaret Randall. Yo nací en Nueva York. Mi familia es de Nueva York. Y cuando tenía diez años, mis padres hicieron un viaje por todo el país porque no estaban contentos en esa ciudad. Ellos querían ver dónde podríamos vivir. Y escogieron Nuevo México. A pesar de que allí se hablaba español, yo no aprendí sino hasta que viajé a España, sola, adulta, en el año 1956. Viví en Sevilla. Y empecé a aprender español. (Mi madre aprendió español en Nuevo México, en la Universidad). No teníamos ninguna raíz con el español en la familia.

yr. ¿Por qué eligió venir a radicar en México?

mr. En 1960, tenía ya a mi primer hijo, en Nueva York. Era madre soltera. Era difícil entonces ser madre soltera. En Nueva York no había muchas condiciones, o sea, no había guarderías, ni cosas así. Yo trabajaba mucho y casi no veía a mi hijo. Entonces, en el año 1961, no sé por qué, se me ocurrió que si veníamos a México a lo mejor podría pasar más tiempo con mi hijo. Es una de esas cosas que no me explico tanto ahora, pero resultó.

yr. ¿Me podría hablar un poco sobre la atmósfera cultural de la época en la que la revista El Corno Emplumado fue concebida?

mr. La época en que El Corno Emplumado tuvo sus ocho años de vida fue una etapa cultural muy poderosa, de distintas maneras, en las artes, en política, en las relaciones bifronterizas. En México, algunos de los grandes artistas acababan de fallecer −Diego Rivera, Tina Modotti, etc.−, y sus espíritus y trabajo aún permeaban la atmósfera. Otros aún vivían: David Alfaro Siqueiros, Anita Brenner, Rufino Tamayo. La política mexicana de ofrecer refugio a los artistas que sufrían persecuciones en otros lados trajo a refugiados como Leonora Carrington, León Felipe y Mathias Goeritz. Jóvenes artistas, como Elena Poniatowska, Carlos Monsiváis, Juan Martínez, Juan Bañuelos, Felipe Ehrenberg y José Luis Cuevas, comenzaban a aparecer en la escena. En los Estados Unidos, acabábamos de emerger del macartismo y comenzábamos a buscar voces que habían sido silenciadas durante las décadas previas. Alrededor del continente −diría que alrededor del mundo−, la década de los años sesenta fue una época de efervescencia cultural, rebelión y resistencia a la sofocación e hipocresía social.

yr. Para la materialización del Corno Emplumado, ¿qué revistas tomaron como modelo para su contenido y formato?

mr. Aunque El Corno Emplumado fue sólo una de un gran número de revistas literarias que emergieron a principios de los años sesenta, no tomamos a ninguna otra revista como modelo para su contenido y forma. Queríamos ser originales. Vimos que la forma y el contenido estaban íntimamente conectados. Hablamos sobre crear una revista donde las páginas se conformaran con el trabajo que imprimíamos, en lugar de que el trabajo se conformara a las páginas. Por ello, a veces, imprimíamos en las páginas poemas en líneas verticales. Queríamos ser modernos, únicos, libres.

yr. Las notas de los editores ¿las escribían usted y Sergio Mondragón o usted las notas en inglés y Sergio las notas en español?

mr. Al principio Sergio escribía las notas de los editores en español y yo la notas en inglés, aunque algunas veces traducíamos la nota de uno de los dos y la publicábamos en forma bilingüe. Más adelante, comenzamos a diferir en nuestros conceptos de lo que una revista debía ser y nuestras notas también comenzaron a diferir.

yr. A veces publicaban a autores que no mandaban colaboraciones. ¿Cuál era la intención de esto? ¿En qué se basaban para elegir a los colaboradores?

mr. Siempre buscábamos trabajos de aquellos que admirábamos: poetas, artistas, cuyo trabajo queríamos mostrar. Mientras ganábamos reputación, más y más escritores nos buscaban y enviaban su trabajo de manera espontánea. Diría que fue una mezcla: si sabíamos que un poeta, en particular, estaba escribiendo algo que nos emocionaba, le preguntábamos si podíamos publicarlo en la revista. Pero también recibimos bastantes colaboraciones y publicamos muchas de éstas.

yr. ¿Estaba interesada en la poesía política cuando comenzaron a publicar la revista o su interés comenzó allí y se fue desarrollando?

mr. Personalmente, no estaba muy relacionada con la poesía política cuando comencé a editar El Corno Emplumado porque venía de los Estados Unidos, donde el macartismo había puesto una sordina en todo lo político. Leí los primeros grandes poemas políticos después de venir a México. No obstante, con los años el término “poesía política” me ha comenzado a disgustar. No me llamo a mí misma una poeta política. Creo que la poesía puede ser de cualquier tema: de tema social, de idea, del amor, del miedo, del paisaje, etc. De manera más amplia, todo es político.

yr. ¿Me podría hablar sobre las intenciones estéticas que compartían Sergio Mondragón y usted durante la publicación del Corno Emplumado?

mr. Compartíamos un interés por lo nuevo, lo experimental, lo verdadero y lo dinámico.

yr. ¿La idea de intercalar ilustraciones con literatura fue preconcebida?

mr. Estábamos interesados en reproducir la palabra escrita con las imágenes visuales. Y esa era una manera en que podíamos hacerlo.

yr. Las ilustraciones que se publicaron en la revista no están relacionadas con los textos publicados: ¿a qué se debe esta decisión?, esto es, ¿cuál era la función de la gráfica?

mr. No veíamos al arte visual como algo que necesariamente debiera ilustrar la palabra escrita, ni viceversa. Sentíamos que cada trabajo creativo debía defenderse por sus propios méritos. A veces, como en el ejemplar donde incluimos una sección de poesía indígena, acompañamos esos textos con dibujos de artistas indígenas de Guerrero. Aunque, generalmente, cada contribución a la revista era completa, bajo sus propios términos.

yr. En El Corno Emplumado publicaban antologías poéticas. ¿Por qué no publicaban antologías en prosa?

mr. Siempre consideramos a El Corno Emplumado, primeramente, como una revista de poesía. Debido a que nuestro mayor contacto era con poetas, nos fue fácil obtener pequeñas antologías de poemas de diferentes países. Pero pienso que si hubiésemos recibido una antología de prosa, que nos gustase, seguramente la hubiésemos considerado para su publicación. Un límite de espacio también pudo haber entrado en esta decisión.

yr. En febrero de 1964 se llevó a cabo el “Primer Encuentro de Poetas Americanos”, en la Ciudad de México. En esas reuniones, acordaron publicar una revista, Nueva Solidaridad, donde traducirían más poesía americana, incluso al portugués, no obstante, no he podido encontrar información sobre esta revista, ¿se llegó a publicar?

mr. No. Fue nuestra intención publicar Nueva Solidaridad y expandirnos para incluir otros idiomas de América, pero no pudimos hacerlo. Creo que Miguel Grinberg, en Buenos Aires, pudo haber producido un ejemplar de dicha revista, pero, en cualquier caso, no prosperó.

yr. Desde su postura actual, ¿cómo evalúa la importancia de El Corno Emplumado con relación a las otras revistas literarias de la época?

mr. En aquel entonces, y ahora, veo que la primera importancia de El Corno Emplumado es la de puente, una manera de conectar lo que estaba sucediendo en los hemisferios del sur y del norte, entre creadores, que eran apartados por maniobras políticas, pero que tenían mucho que decirse. El hecho de que la revista fuera bilingüe ayudó mucho en este esfuerzo. Teníamos lazos con otros proyectos literarios y culturales, pero creo que esto nos apartaba.

yr. ¿Qué diferencias y similitudes tenía El Corno Emplumado con respecto a las otras revistas?

mr. Nuestra mayor diferencia fue que éramos bilingües.

yr. En varias ocasiones usted se ha lamentado por no haber publicado más mujeres en El Corno Emplumado. ¿Cómo ha intentado asumirlo en su trabajo posterior?

mr. La falta de mujeres en las revistas literarias, y en las publicaciones en general, no era algo que se limitaba, en aquel entonces, a México. Era a nivel mundial. Y continúa, en gran amplitud, aunque las cosas han mejorado desde la década de los sesenta. Descubrí el feminismo mientras vivía en México, en 1969. Tuvo una influencia muy profunda en mi vida personal y profesional. Desde entonces, he producido muchos libros de historia oral con mujeres, en un intento por darles la voz a personas que han sido silenciadas por el patriarcado. Mi feminismo informa todas las áreas de mi vida, así que, lógicamente, está presente en mi poesía y en cómo vivo mi vida. Hace poco produje una gran antología bilingüe, de ocho décadas de poesía cubana, Only the Road/Sólo el camino, publicada por la Duke University Press. Casi la mitad de los 56 poetas que incluyo son mujeres, algo muy inusual para cualquier antología, en cualquier lugar. Siempre estoy consciente de otorgarles la palabra a las mujeres, porque hemos sido silenciadas e ignoradas durante mucho tiempo.

yr. ¿Durante la época de El Corno Emplumado, además de su vivencia como editora, cuál sería alguna experiencia significativa para usted?

mr. Durante los años de El Corno Emplumado nacieron mis tres hijas: Sarah, Ximena y Ana. Esos fueron, sin duda, momentos muy importantes para mí. Y por supuesto, el movimiento estudiantil de 1968 marcó mi vida de manera muy significativa. Estoy segura de que hubo otras experiencias más, pero todas éstas, siento, fueron los más importantes.

yr. En El Corno Emplumado es muy clara la postura de los dos, Mondragón y usted, en cuanto al papel de la literatura y la función del escritor: alcanzar una utopía social mediante la literatura. ¿Ha cambiado su concepción? Para usted, ¿cuál es la importancia, en la actualidad, de la literatura y del escritor?

mr. La literatura es extraordinariamente importante en mi vida y, creo, en el mundo. Hoy, cuando tanto discurso de odio, tantas mentiras, tantas de las llamadas noticias “falsas” se han vuelto parte del discurso general, dependemos de la literatura para decirle la verdad al poder. Para responderle al criminal que está en la Casa Blanca, que habla de muros, de división, de odio, nosotros los poetas tenemos que responder con el lenguaje real de la vida.

yr. En los números finales de El Corno Emplumado, del número 27 en adelante, aparecen más entrevistas, ensayos, incluso reseñas y referencias a Cuba y la revolución, y menos poesía que en los números anteriores. ¿A qué se debieron estos cambios?

mr. En enero de 1967, Sergio y yo fuimos invitados al “Encuentro con Rubén Darío”, una reunión de poetas que celebraban el centenario del gran modernista nicaragüense. Este evento fue en Cuba y fue auspiciado por Casa de las Américas, en La Habana. Marcó nuestro primer encuentro directo con la revolucionaria Cuba. Ahí conocimos a muchos jóvenes poetas, escritores y artistas visuales. Así es como nuestro contacto con la escritura y el arte cubano comenzó. Regresé un año después, en enero de 1968, al Congreso Cultural de La Habana, donde continué explorando la revolución y conocí más escritores y artistas. En ese entonces, El Corno Emplumado se distribuía en todo el mundo, pero, principalmente, en los Estados Unidos y México. En los Estados Unidos hubo un silencio resonante con todo lo que pasaba en Cuba. Publicábamos obra cubana porque nos gustaba, pero también porque sentíamos que era importante que los lectores estadounidenses tuvieran acceso a lo que estaba pasando en ese país.

yr. Esta pregunta tiene que ver con Cuba y tu postura política. ¿Al enterarse del “caso Padilla”, cambió tu opinión sobre el ideal revolucionario?

mr. No, el “caso Padilla” no cambió mi opinión sobre el ideal revolucionario, aunque pienso que la Revolución Cubana cometió un error al hacer de Padilla un chivo expiatorio y, también, al darle mucha importancia al caso. Este fue uno de varios incidentes durante un periodo oscuro de censura, que, siento, la Revolución Cubana ha superado y rectificado de manera extensa. En sociedades altamente controladas, siempre hay gran peligro de censura. Y uno debe cuidarse.

yr. Después de radicar once años en Cuba, se va usted a Nicaragua, a continuar apoyando a los grupos revolucionarios. ¿En qué momento se percató de que quería seguir luchando por los derechos de los venidos a menos en otros lugares de Latinoamérica?

mr. Desde mucho antes me interesaba el cambio social. El haber participado en el Movimiento Estudiantil de 1968 me mostró lo que un gobierno es capaz de hacerle a los jóvenes para “mantener el orden”. Cuba me mostró cómo se veía una sociedad radical con cambio social. En Cuba conocí a revolucionarios de otros países latinoamericanos. Especialmente, me interesé en Nicaragua después de que los sandinistas salieran victoriosos, en 1979. Sigo interesada en diferentes modelos de cambio social, pero, a mi edad, ya no tengo la energía ni el deseo de seguir este interés de manera tan activa.

yr. ¿Cuándo se dio cuenta de que la liberación de la mujer también era importante para alcanzar una mejor sociedad?

mr. Como te dije, descubrí el feminismo en 1969. Cuando hablo de feminismo, no estoy hablando de la lucha entre el hombre y la mujer, sino de una herramienta para el análisis del poder. Desde entonces, ha sido obvio, para mí, que el verdadero cambio social no puede ser posible a menos que todo sector social sea tomado en completa consideración: mujeres, personas de color, la comunidad lgbqt, aquellos con diversas capacidades físicas y mentales. Cualquiera considerado diferente por la cultura hegemónica. A menudo los partidos políticos o los movimientos revolucionarios hablan “en pro” de un sector social en particular. Creo que es importante que cada sector social hable por sí mismo, que ejerza verdadero poder en la lucha por el cambio.

yr. ¿Cuál fue la recepción de El Corno Emplumado en los Estados Unidos y en Latinoamérica?

mr. El Corno Emplumado fue recibida con entusiasmo en cualquier lugar que la enviamos. Esto fue igualmente verdad en los Estados Unidos, en Latinoamérica y en muchos otros países. Aunque sólo podíamos producir 3,000 copias por cada número y mandar pequeños paquetes de 5 o 10 para cada receptor, las personas intercambiaban la revista y nuestro alcance fue bastante amplio. Varias librerías tenían subscripciones, lo que permitió que muchas más personas la leyeran.

yr. ¿Era visible el control del Estado y la censura? ¿Se sintieron vigilados por alguna autoridad o grupo político?

mr. Sí. La censura del Estado fue real y visible durante los años en que publicamos El Corno Emplumado. Cuando anunciamos que nuestro siguiente número estaría dedicado al trabajo en Cuba, la Unión Panamericana −extensión cultural de la Organización de los Estados Americanos (oea)− nos amenazó con cancelar 500 suscripciones, si lo hacíamos. Está de más decir que no lo dudamos y perdimos esas valiosas suscripciones. Tuvimos patrocinio de varias ramas del gobierno mexicano: la Secretaría de Educación Pública, la Presidencia, Bellas Artes, etc. Cuando la revista se puso al lado de los estudiantes, en 1968, perdimos esos subsidios. Y por supuesto, la revista fue forzada a cerrar, como consecuencia de nuestro involucramiento personal en el movimiento estudiantil. Así que el control gubernamental y la censura estuvieron siempre muy claros para nosotros.

* * *

Margaret Randall continúa tan vital como siempre. Y lo demuestra cuando lee poesía, con una voz apasionada y firme. A sus 82 años se mantiene activa, escribiendo poesía, visitando ferias de libros y congresos de literatura. Encontrar el equilibrio entre disciplina, activismo y humildad es una empresa difícil, pero Margaret Randall ha logrado justo eso. Sorprende su fuerza para continuar luchando contra los poderes opresores por medio de la poesía, a la manera de Víctor Hugo y demás poetas sociales del siglo xix. Ella ha logrado desdibujar las barreras tanto lingüísticas como culturales en su vida y en la vida de muchos escritores, lo cual la vuelve un puente entre dos culturas. Ha publicado y continúa publicando la obra de distintos poetas de todas partes del mundo, ya sea en antologías o, bien, en libros de su autoría, con sus respectivas traducciones: los más recientes, 12 poetas, Antología de nuevos poetas estadounidenses y El Rizoma como un campo de huesos rotos. Dicha tarea la comenzó desde sus años como editora de los 31 números de El Corno Emplumado, revista que sigue inspirando a nuevas generaciones.

Yasmín Rojas es maestra en Literatura Mexicana y traductora. Su cuenta de Twitter es @yspora

Yasmín Rojas es maestra en Literatura Mexicana y traductora. Su cuenta de Twitter es @yspora

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

-

Pingback: Kontribusi Fiksi Ilmiah terhadap Sastra Perlawanan Arab - Matatimoer Institute