Mariano Azuela and the “Brown Scare”

Robert McKee Irwin

On March 13, Manuel Gutierrez organized a symposium titled Mariano Azuela y la narración de lo urgente. Primer centenario de Los de abajo. Among the participants were Maarten Van Delden, Ignacio Sánchez Prado, Adela Pineda Franco, Anadeli Bencomo, Max Parra, Brian Price, Pedro Palau and Bruno Ríos. We are delighted to share Robert McKee Irwin´s piece to our readers. This event was possible thanks to Rice University, Dean of humanities, the Department of Spanish and Portuguese, Public Affairs Multicultural Community Relations, the Consulate General of Mexico and Literal.

***

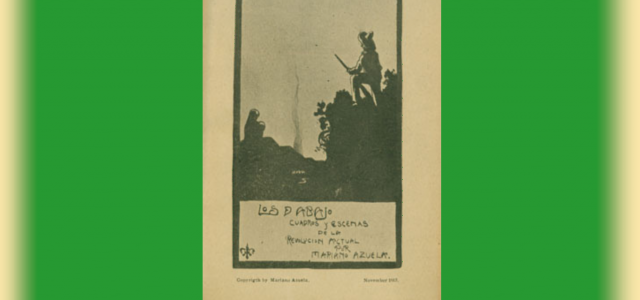

In It is well known that the most emblematic novel of the Mexican Revolution, the one whose rise to fame through debates on national literature in the mid-1920s, Mariano Azuela’s Los de abajo, was originally published in El Paso, Texas in 1915 during the author’s brief exile in that border city. While there has been some historical interest, mainly on the part of US based scholars dating back to the 1930s (John Englekirk, Lawrence Kiddle, Ernest Moore, Stanley Robe, and most definitively Luis Leal) on studying this edition and casting light on Azuela’s sojourn in El Paso, the book’s history and Azuela’s corresponding literary biography are so embedded in literary nationalism that the border circumstances that allowed their initial production are mostly forgotten. Azuela’s stay in El Paso was after all quite short, lasting roughly two months. The fact that he stayed in the Mexican part of town, which was culturally something of an extension of Ciudad Juárez, perhaps made it seem as if he had never left Mexico at all. However, such an interpretation of his stay there ignores, as much historiography on the Mexican Revolution does, the ways in which revolutionary warfare extended into the US borderlands. Indeed the period of Azuela’s stay in El Paso coincided with a period of significant anti-Mexican violence occurring from Brownsville to Nogales and whose epicenter would become El Paso less than a month after Azuela’s return to Mexico. My paper today locates the publication of the first (and second) edition of Azuela’s greatest revolutionary novel within the context of revolutionary borderlands violence that has never to my knowledge been acknowledged by literary historians.

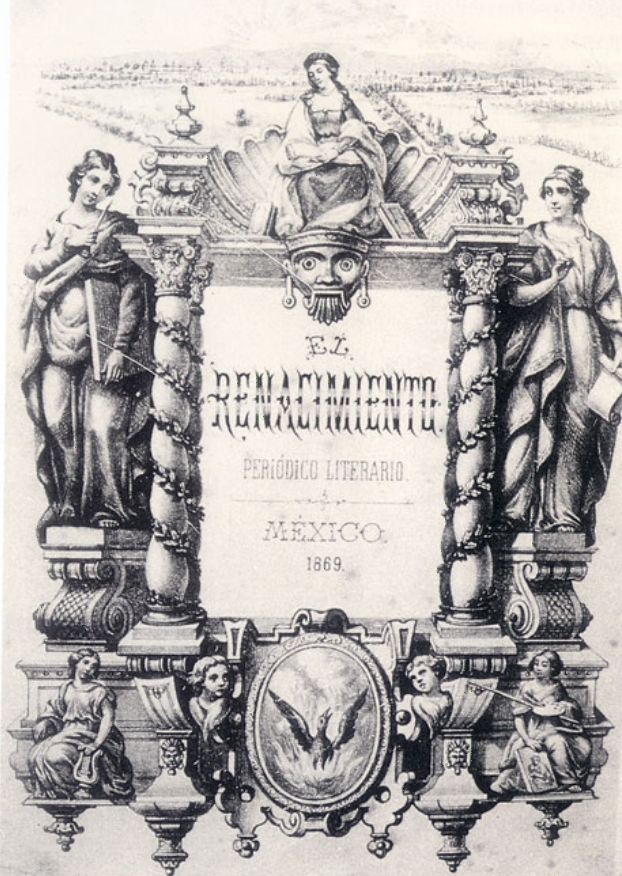

A few years back, at a moment of rising interest in inter-American studies, I looked into the connections between the American literary renaissance of the 1850s and the Mexican Renacimiento, the literary magazine through which Ignacio Altamirano sought to promote literary nationalism in Mexico in 1869 and found that “even as readers of this new American literary criticism have been captivated by one fascinating unexpected transamerican literary connection after another, it is important that we not lose consciousness of the bigger reality. What is most remarkable about this pair of literary renaissances of neighboring nations is not so much their parallelisms […] but their utter lack of interest in each other” (see Irwin “The American Renaissance and the Mexican Renacimiento: The Long Critical Diconnect in the Americas,” The New Centennial Review 8.1, 2008: 238). If it might be expected that Whitman, Hawthorne, Thoreau and their lot sought out connections in Europe before looking to their South American neighbors, but it may be less intuitively apparent just how little interest Altamirano and his collaborators showed in US literature, with Edgar Allan Poe being just about the only US writer they cared much about at all. With few exceptions, Spanish speaking Henry Wadsworth Longfellow being another one, there was very little crossborder circulation of literary texts, much less translation thereof, prior to the 1920s. In other words, the international prestige of US literature in the late 1800s was no greater than that of Mexican literature, at least in the context of the Americas.

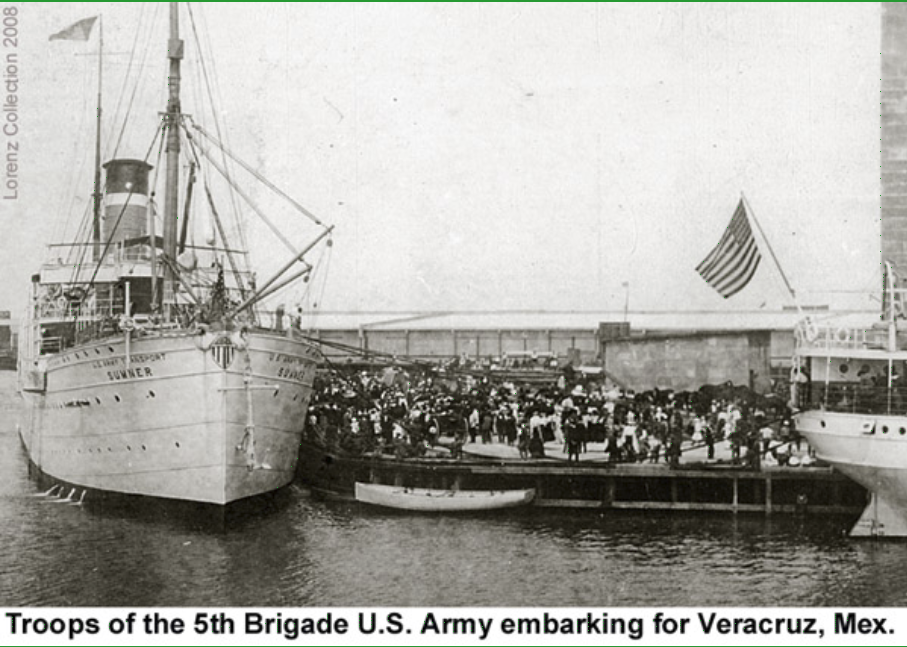

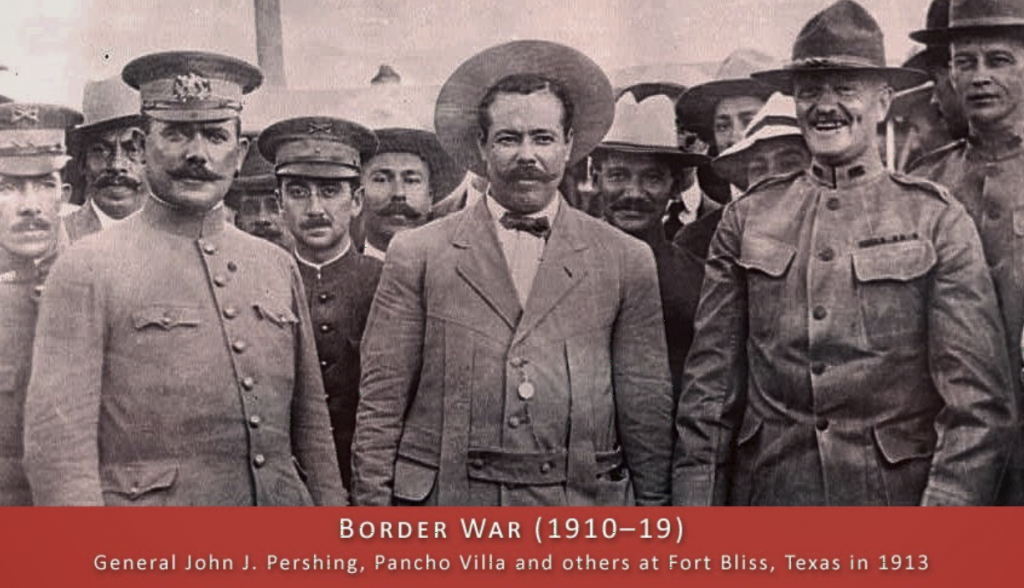

This pronounced disconnect between national literary traditions extends in many ways to national histories, which get told in such nationalist terms that some of their most obvious transnational implications are easily forgotten. The 1910s in the US is the period of World War I, while in Mexico it’s the epoch of the great revolution; for the most part these are two separate histories. While Mexicans may remember the invasion of Mexico in 1914, leading to the US military occupation of Veracruz, due in part to the fear that Victoriano Huerta’s government was entering into a military alliance with Germany, or recall Pancho Villa’s skirmishes with US authorities, few US Americans have any idea that the United States had attacked Mexico in the middle of the latter nation’s revolutionary war.

Meanwhile, aside from Pancho Villa’s legendary cross border raid of the New Mexican town of Columbus in March of 1916 and the US’s unsuccessful punitive campaign to hunt down Villa over the course of the following year, memorialized in corrido and a major justification for Villa’s status as a folk icon (a “borderlands saint” as my colleague Desirée Martín puts it), very little of the revolutionary violence taking place on the US side of the border, which ignited what the US press sometimes referred to as the “brown scare” of the 1910s, is remembered today in either nation. While Azuela himself has little to say about the turmoil on the US side of the border, had he stayed another month in El Paso it might easily have killed him – and he might easily have been inspired to write another chapter into his book complicating Luis Cervantes’s experience in el Norte; I argue that a full contextualization of this novel’s publication requires that it be considered from within the transnational context of the borderlands.

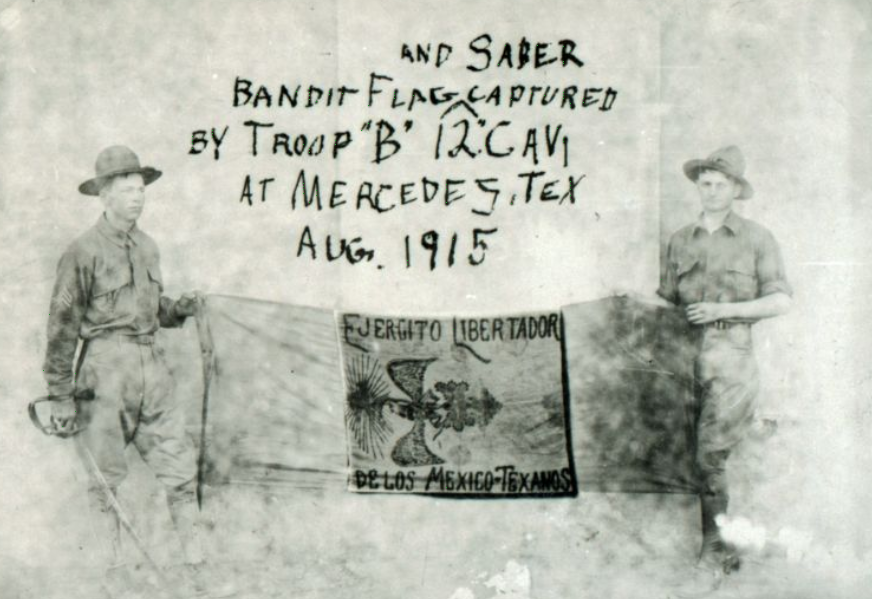

To make clear that the borderlands violence I have mentioned goes well beyond a single cross border raid by Villa, let me provide some additional historical data. In January 1915, the Plan of San Diego, Texas (not San Diego, California) was launched. Its authors aimed to win back the states of Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, Alta California and Colorado for Mexico, forming an alliance with “Indians,” “Negroes” and Japanese, in the process executing “every North American [male] over 16 years of age.” This plan, putatively authored in collaboration with Huertistas, but financed in part by Venustiano Carranza’s army, led to a series of raids on properties and infrastructure in the Río Grande Valley in the summer of 1915 that were quelled only when president Woodrow Wilson announced on October 19 that the United States would recognize Carranza as Mexico’s president.

Azuela’s arrival in El Paso coincided with this truce. Although his own revolutionary ties had been with Villistas, Azuela reached agreement with the publishers of a Carranza financed local newspaper, El Paso del Norte, to publish his still incomplete novel in installments beginning October 27, only eight days after the aggressions inspired by the Plan de San Diego ceased. He wrote the remaining chapters (roughly a quarter of the novel) using equipment belonging to the newspaper’s publishers. It came out in 23 daily installments, six days a week, with the final chapter published on November 21. The quality of this edition was deplorable; according to Robe: “No author of a truly significant novel would want to have his creation printed as a serial in the newspaper of a minority group in a foreign country which could not promote and sell the work and which lacked even adequate typographical facilities for printing a modest book” (98). Nonetheless, this was Azuela’s only means of making a living during these months.

The novel generated some early positive feedback from fellow exiles, to whom Azuela had read parts of it, and some criticism that was quite threatening from some Villistas in Juárez who warned Azuela to stay on the US side of the border. El Paso del Norte, the publisher, then printed the novel in book form on December 5, generating its first two reviews from friends of Azuela in El Paso del Norte in December of 1915, historical material that was compiled by US based scholars of Azuela a generation or so ago. I’ll add that even as Englekirk, Kiddle, Robe and, later, Luis Leal, were assembling and publishing this literary history, they failed to pay attention to what was going on in El Paso at the time; thus, Texas is remembered by Azuela scholars as a safe haven where the writer escaped the perils of the Revolution and found sufficiently peaceful conditions to publish his great Mexican novel.

The day before the second of the two reviews was published on December 20, Carranza’s forces took Ciudad Juárez. Azuela, on that same day, took advantage of the ensuing confusion and crossed over into Mexico, travelling back to Guadalajara and joined his family before moving soon thereafter to Mexico City, where a few years later, in 1920, he would publish another edition of the novel, which he considered to be the third, although literary historians list it as the fifth, taking into account a serialized and then a book edition published in Tampico (both apparently lost), without Azuela’s permission, in 1917.

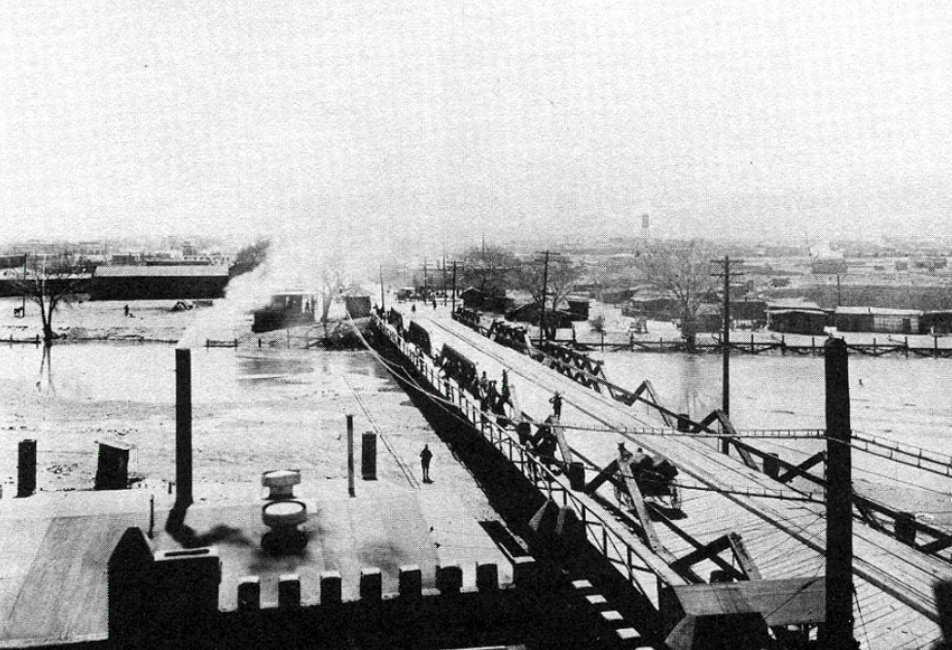

It should be noted that in the days following the publication of the final serialized installment of the novel in El Paso del Norte the Battle of Nogales, Sonora carried over across the border, involving some skirmishes with US troops stationed in Nogales, Arizona. Villa, antagonized by the US recognition of the Carranza government, had made threatening statements regarding US presence in Mexican territory. Some three weeks after Azuela’s return to Mexican soil, on January 11, 1916, Villa’s troops executed 17 US American mining engineers in San Ysabel, Chihuahua, igniting ire in the US southwest. A mob protest in El Paso turned violent, and the martial law imposed on the city did little to calms things down as US soldiers joined in with the Angloamerican protestors in attacking Mexicans, including women, children and senior citizens, on the streets of the city, and inciting the formation of self defense groups composed of Mexicans from both El Paso and Juárez, whose arrival on the scene no doubt exacerbated the violence into what historians have labeled a race war. The Mexican half of the city was eventually cordoned off, this segregation eventually calming things down.

However, skirmishes continued among Mexicans and Anglos in El Paso and Juárez for weeks to come. Then rumors of typhus in Mexico led to a series of policies that involved giving border crossers, as well as those entering the hospitals and jails of El Paso a chemical bath to kill potentially disease carrying lice. In some cases, including those of the El Paso municipal prison, prisoners were dunked into a mix of kerosene and vinegar while their clothing was fumigated. Just three days prior to Villa’s raid of Columbus, New Mexico, a white prisoner lit a cigarette near one of the chemical baths, igniting it, and causing a massive explosion in the city jail. Flames blocked the exits, making it impossible for many to exit without sustaining severe burns. 27 prisoners, 19 of them Mexican, perished, which inspired rumors that the fire was intentionally set (or if not the use of dangerous kerosene baths was instituted) with the aim of killing Mexicans.

In Los de abajo, from El Paso in May of 1915, four months after the public pronouncements of the Plan de San Diego but two months prior to its launch, Luis Cervantes writes to his former comrade in arms, Venancio, with optimistic ideas of partnering in establishing a Mexican restaurant there. Azuela’s own correspondence does not mention any of the border tensions, which were a constant in the both the Spanish and English language south Texas press of the period. Azuela, who in one of his personal letters written from El Paso jokes about religious extremists shouting on the street but never mentions any threat of violence, seems to take El Paso as a safe haven, fully separate from Mexico and its war, even as the Mexican and Mexican American residents of southern Texas found themselves in the middle of what borderlands historians have called the “Border War,” an offshoot of the Mexican revolution whose dynamics cannot be understood in purely nationalistic terms.

If the invasion Woodrow Wilson ordered of Veracruz was meant as a national provocation, Villa’s antics in Mexico’s northern borderlands can hardly be read in simple national (Mexico vs. United States) terms. Villa was during these years not was depicted in the US press not as a representative of the Mexican nation, but rather as a bandit. This occurred even in the Spanish language Mexican American press – this is indeed the language used to refer to him in El Paso del Norte. Likewise the Plan of San Diego, even if funded by Carranza, was never openly sanctioned by any Mexican government agency, and remained largely unknown in both countries, except in the local context of the Río Grande valley. The borderlands war, for the most part, never became truly national in scope on either side of the border.

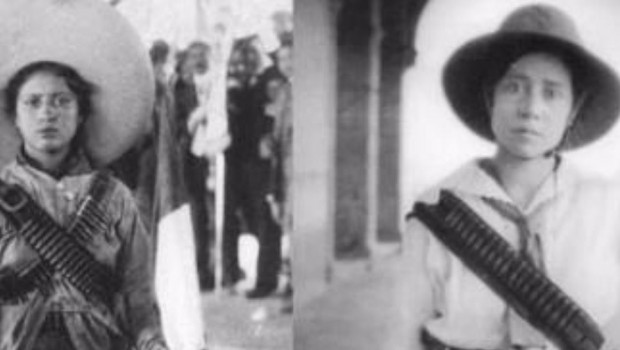

In the United States, the “brown scare” was born out of fears of Mexico’s potentially forming a military alliance with Germany, but extended beyond Mexico itself into the Mexican American communities of the borderlands, which in the conflict’s worst moment led to the massacre of the entire town (including boys as young as fifteen) of Porvenir, Texas, the execution and mutilation of fifteen men and boys by Texas Rangers, who believed, based on apparently shoddy evidence that they town was teeming with Mexican outlaws. While the Mexican Revolution was fought among Mexicans, the US’s enemies of the borderlands war included not only Mexican “bandits” but also US citizens of Mexican origin. It brought to a head long simmering tensions among Anglo and Mexican Americans whose uncomfortable coexistence dated back to the war for Texas’s independence and the US-Mexican war of the 1840s.

Azuela, of course, was not executed or mutilated, nor did he see any violence of this kind first hand. However, in the months surrounding his brief stay in El Paso, all kinds of violence, much of it residual to that of the civil war in Mexico, formed an important part of everyday life for Mexicans in the US borderlands. This borderlands war was just as real for residents of El Paso, San Diego, or El Porvenir, Texas or Columbus, New Mexico, or Nogales, Arizona, as the Mexican Revolution was for those of Celaya, Agua Prieta, Zacatecas or Guerrero (and we will not even address what was going on farther west, with the Magonista led battles of Tijuana that included the participation of US American volunteers). My point here is to turn attention back to El Paso and the borderlands to recast the novel of the Mexican revolution in the transnational terms of the war itself. I’ll insist that Los de abajo is both a Mexican national novel, and a Mexican American novel of the borderlands, and that Azuela’s two months in Texas should be accounted for in our critical readings of the novel, its circulation and its eventual canonization.

Robert McKee Irwin is the author of Mexican Masculinities, Bandits, Captives, Heroines and Saints, The Famous 41, El cine mexicano se impone and Los cuarenta y uno among others.

Robert McKee Irwin is the author of Mexican Masculinities, Bandits, Captives, Heroines and Saints, The Famous 41, El cine mexicano se impone and Los cuarenta y uno among others.

Posted: April 7, 2015 at 5:30 am