Look Closely, Look Again

Laura A. L. Wellen

“We forge street corners

like tempered gold

these city streets are swords

sharpened to erasure points

we squire the night

ships passing

lights flashing

morse code

long and short

translating the light”

– Holly Walrath, “Out of the Labyrinth”

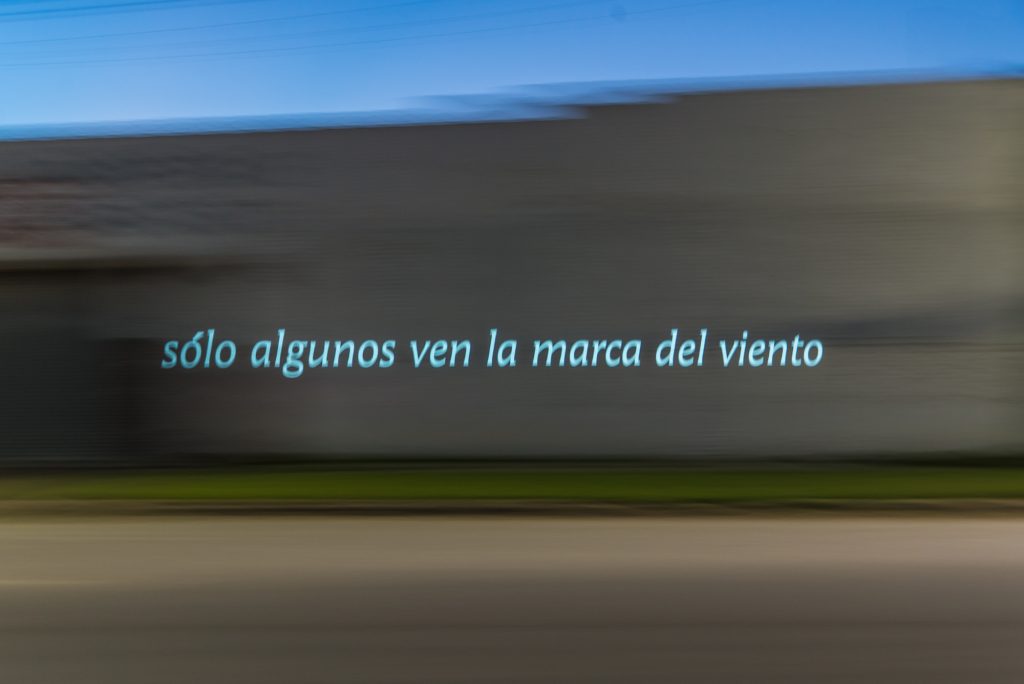

I meet Pablo Gimenez-Zapiola at dusk on a Wednesday evening. As he arranges the cables and extra power strips for the machinery he’s designed to fit inside his car, his enthusiasm is contagious. Gimenez-Zapiola is gearing up for Eastext, an ephemeral, site-specific new work that he will present on October 13, 20, and 27 across the East End. Gimenez-Zapiola, known in Houston for his photographic work and video projections, developed Eastext with the support of a Houston Arts Alliance grant. The piece consists of a moving projection of texts written by Houston-based poets Eloísa Perez Lozano, John Pluecker, Vanessa Torres, Holly Walrath, and Gwendolyn Zepeda. Their words wander and drift across the sides of buildings, trees, and fences as Gimenez-Zapiola drives the projector through the neighborhood.

As I clamber into the backseat of his car, I feel a rush of excitement at the handmade quality of the machinery Gimenez-Zapiola has conceived, designed, and built for the project. In Guatemala, a chapuz is a fix, something that is created out of a miscellany of parts, something that works, but threatens to dissolve into chaos at any moment: there’s a beautiful chapuz-ery to Gimenez-Zapiola’s device. He laughs as he explains how it works: it’s definitely a Latin American solution, we agree. As Gimenez-Zapiola starts circling through the neighborhood, he keeps one hand on the laptop in the passenger seat, manually changing the text that is being projected through the passenger side window. We pass schools and bars, gas stations and homes, and somehow he manages to snap photographs of the projections while he drives. Occasionally, his car veers precariously close to a ditch, as he arranges the camera and projector, leveling the image which often tries to slope up or down. We stop at one point to make some adjustments, and a man comes over and observes what we’re doing.

Gimenez-Zapiola is an architect by training, and has worked extensively as a graphic designer and photographer. “The cameras, the computer, are extensions of me,” he writes. Despite the digital nature of many of his works, Gimenez-Zapiola believes in the importance of drawing and sketching. “To put the first draft of an idea on paper, there is no faster tool than a pencil. And, in that sense, I think the creation process has to be organic.” In many ways, Eastext is an organic extension of Gimenez-Zapiola’s earlier projection work, which he has shown at Anya Tish Gallery, Cherryhurst House, and on trains and silos around the city. This time, though, the work is intended to connect specifically to the Latino community that lives in the neighborhood. Gimenez-Zapiola selected poems in or between English and Spanish, and many of them reflect on the experience of living between places, of travel and transition. “I’ve only crossed over el río on foot or by car, / answered the border patrol’s preguntas with confidence,” writes Eloísa Perez Lozano in her poem How far you are from me.

Gimenez-Zapiola moved to the U.S. from his native Argentina in 2002, rebooting his professional life in the United States as a result of the Argentine economic crisis of the early 2000s. As we circle back past Rincón Social, the words of a John Pluecker poem flicker and travel across the corrugated metal building: “Salvaje. Sal de viaje. / Viajar un requisito.” This is not only an intellectual exercise, but a personal meditation on change and movement. “I think seeing is one of the most powerful tools the human being has,” Gimenez-Zapiola writes. “And I mean seeing through your eyes, but from your soul. So my way of working is connecting with my surroundings and establishing a dialogue with it, trying to find the beauty existing around us, trying to extract it from everywhere I go. I shoot every day no matter what; it can be a tree, the texture of the street, a crack on the wall, a light pole, the sky, a flooded street, a bridge… Almost everything captures my attention.”

As we drive slowly through the night streets, the words ripple and bounce off the surfaces they encounter. Beaming into wooded areas, they seem to break apart across the spaces between the trees. They undulate over corrugated metal and explode across chain-link fences, with their diamond-shaped gaps. The transitory nature of the moving text interests Gimenez-Zapiola, and he points to places where the words dissolve into space. Indeed, the ephemerality of the text speaks to an embrace of constant change. This is not only a poetic reflection on the experience of migration but, even more specifically, reflects a lived reality on the East End of Houston, which is rapidly changing as the city’s developers push into the neighborhood.

“See what you want,” writes Houston’s first poet laureate, Gwendolyn Zepeda, in her poem Flirt.

Gimenez-Zapiola’s training as an architect also provides a mooring for the project’s exploration of built space. Projecting onto the structures of the neighborhood, the words seem to draw themselves onto the found environment. It’s a striking difference from the ways in which architects normally outline buildings.

Seeing Eastext from the back of Gimenez-Zapiola’s car is a remarkable visual experience, and one quite different from how viewers will experience the piece. From within the car, the viewer moves with the words, and the buildings are the things that change. But when viewers attend Eastext, they will stand or walk through the neighborhood, waiting for Gimenez-Zapiola to meander through the darkened streets. For them, the buildings will be stationary, the text fleeting. Fragments of poems will appear and disappear as if walking through the neighborhood, marveling at its structures.

“Del corazón y el origen / salió iluminando un camino,” writes Vanessa Torres.

Gimenez-Zapiola thinks of poetry as a philosophical practice, deeply integrated to his understanding of making art, and of how we understand visual experience. “…one can achieve strong artistic level in his work if these two elements are present: poetry and craft,” he writes. “And I don’t mean poetry in literary terms, but in terms of the symbolic, elegant, the fine, the beautiful, the sensitive, the imaginative and the original.”

As the words hover and bump, shuffle and linger over everything we pass, the urban fabric of Houston becomes a canvas for thinking about language and lived experience, change and community. In his poem Run, Pluecker writes, “some thing missing / in this stand of trees / or metal poles these / lofty rows & / milky dome”. Words pass over groups of people lingering and chatting near a convenience store and then move on, forward, circling and evaporating. Look closely, look again. Grasp the poems as they vanish, hold onto the community as the neighborhood continues to change.

Eastext is supported by the City of Houston through a Houston Arts Alliance Grant. It will take place in and around El Rincón Social (Oct. 13), GalleryHOMELAND (Oct. 20), and Box 13 (Oct. 27).

Laura A. L. Wellen PhD is a writer and independent curator based in Guatemala City and Houston. In 2016, she co-founded the apartment gallery and residency Yvonne in Guatemala; she is the co-founder of the Houston-based project Francine. In 2016, she is a writing fellow at the Core Critical Studies Program of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Her art criticism has been published in ArtForum, Artishock, Art Lies, Art Review, Arts + Culture Texas, Pastelegram, and …mightbegood. Recent essays have appeared in the artist monographs Diana de Solares: The Material Space of Radiance (2016) and A Line, However Short, Has an Infinite Number of Points: Andrés Ramírez Gaviria (2016).

Laura A. L. Wellen PhD is a writer and independent curator based in Guatemala City and Houston. In 2016, she co-founded the apartment gallery and residency Yvonne in Guatemala; she is the co-founder of the Houston-based project Francine. In 2016, she is a writing fellow at the Core Critical Studies Program of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Her art criticism has been published in ArtForum, Artishock, Art Lies, Art Review, Arts + Culture Texas, Pastelegram, and …mightbegood. Recent essays have appeared in the artist monographs Diana de Solares: The Material Space of Radiance (2016) and A Line, However Short, Has an Infinite Number of Points: Andrés Ramírez Gaviria (2016).

©Literal Magazine

Posted: October 12, 2016 at 9:55 pm