The Mobile Poet

George Franklin

Translated by Grady C. Wray

Gisela Heffes is a poet of what is no longer present or what is in the process of vanishing. Her diction is restrained, avoiding any straining after a false profundity, and the poems in this collection typically enact moments of straightforward experience: glimpses of neighborhood cats, memories of her father, of walking with her daughter. She is aware of how easily such moments vanish, and she is determined not only to preserve them in her poems but to restore them to immediacy.

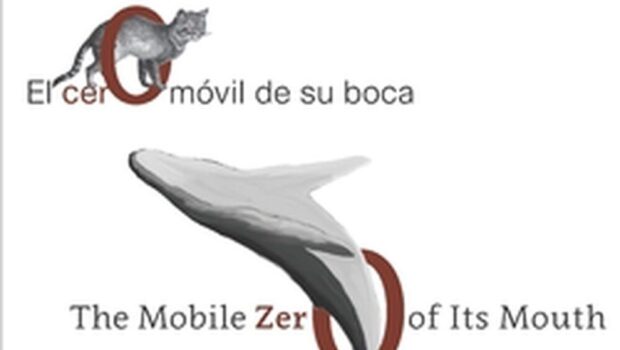

Heffes, however, is not naïve and does not succumb to nostalgia. Poems are no more magic spells to bring back what is gone than snapshots are the people and places they image. She also understands absence, that “mobile zero” of the title, and knows we represent our losses in language the way zero embodies absence in numbers. In El cero móvil de su boca/The Mobile Zero of Its Mouth (Katakana Editores 2020), she circles the edges of that zero, exploring and remembering. In her poem “Words,” Heffes recalls walking in Buenos Aires and writes of her father:

His absence left an impression like a presence.

His old apartment.

His neighborhood.

The restaurants where we would go.

The restaurants are not there either.

A tombstone.

That’s left.

A gray tombstone, surrounded by many more.

Gray and worn away.

What is remarkable about Heffes’ poetry is that she is able to find refuge in that absence, a place to live inside the zero.

The setting for the book is a summer vacation in a distant city, a liminal space where the poet can examine her life away from her obligations as a professor of Latin American literature in Houston. Summer here becomes something far larger than a time of the year. Distance becomes perspective; it allows her to be “ex-centric,” to be herself absent from the “normal” center of world. This is not the absence, though, of the poet separating herself from that world with its injustices and crimes. For example, in her poem “Hate,” the thousands of kilometers between Heffes and the mass murder of Latinos at a supermarket in El Paso only intensify her awareness of her own vulnerability, of being “the other.” The relative safety of the vantage point, summer and the refuge of her family and poetry, makes the event that much more threatening.

The poems each begin with a simple declarative sentence, such as “It makes me sad to think about what’s left” or “I think about my dad.” From there, we follow Heffes where memory of lost things takes her, “A place inhabited by people who are foreign to us. / An incalculable sphere we don’t see or touch.” In order to arrive at such a place, she travels light. Heffes avoids any phrase that smacks of high-flung romanticism. This is not a poetry of blood and infinity; it is a poetry of particulars, of finding emotion in the quotidian and the real. When she laments extinctions, she tells us of “Turtles entwined in plastic. / Oil like black jam spread on the bodies of penguins.”

Although Heffes is from Argentina, her poetic forebears may well be the twentieth century American poets who learned so much from translations of Chinese and Japanese poetry about how to make a poem real. Her approach especially brings to mind the clarity of Willliam Carlos Williams’ late poems, where he also thought long and hard about what has been lost and where memory takes us, where, as he put it, “A / world lost / a world unsuspected / beckons to new places / and no whiteness (lost) is so white as the memory / of whiteness.”

In Heffes’ case, her losses have made her cosmopolitan in the best possible sense of that word, what Democritus meant when he said, “To the wise man, the whole cosmos is his home city.” In “Transitory,” Heffes explains, “The city of my refuge is not the city where I reside. / I reside in many cities.” In “Home,” a woman in California notices her accent and wants to know “Where is home?” Heffes replies:

I told her my “home” is “mobile,” and it’s my family,

my children, my husband.

My mom, my brother, my nieces and nephews.

Friends.

There are many “homes,” I explained.

Not only one.

And now, in this magnificent city.

The city of wild weeds.

Of yellow flowers.

The bilingual city.

Where people ride bicycles.

Yield and look at you with a genuine smile.

It can also be “home.”

Although only for six weeks.

I think about what “home” is for others.

I wonder if I might just be rootless.

If Heffes is rootless, she has found a way to embrace that condition by recognizing how common it has become. She knows that the planet into which the roots were planted is changing due to our actions and tossing us into an unpredictable future. Species are racing toward extinction, toward “an emptied earth.” She, as well as the rest of us, exists in a moment of radical contingency, and The Mobile Zero of Its Mouth responds to that moment. If a post-apocalyptic reader happened upon Heffes’ book in the ruins of a library or bookstore, she might nod to herself and think this is how poets lived in those last days, making refuges out of poetry, out of family and friends, cats, and memory, preserving and recreating the world in poems. That same reader might also wonder, not wrongly, whether this book was a kind of manual for twenty-first century survival, a book about how to avoid despair.

If the Spanish text in this dual-language edition were not visible on the left every time the reader turns the page, it would be easy to forget the English poems are translations. Grady C. Wray is a talented translator who has given us poets as diverse as Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz and Marcelo Rioseco. The test of poems brought over from one language to another is not merely accuracy; it is whether the poet has found her voice in the receiving language. Heffes’ voice in Wray’s translation is clear and colloquial, so that in her poems we hear a real person speaking to us in words we recognize. Perhaps this is the essence both of translation and of poetry.

Posted: January 29, 2021 at 12:30 pm

![[Wasps]](https://literalmagazine.com/assets/23501100259_5c25d0d0a9_k-e1511412518269-620x350.jpg)