Past and Future of the Mayas meet in New York City

Fernanda Senger

Francisca Chika Cuy, a K’iche’ migrant weaver artist from Guatemala, visits The Met Museum for the first time. She comes to the exhibition Lives of the Gods: Divinity in Maya Art with an interest in learning about her ancestors and showing it to her son Brandon. The exhibition, which is organized by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Kimbell Art Museum, runs through April 2nd in New York and then travels to Fort Worth, Texas, where it will be on view from May through September, 2023. In this chronicle, historian Fernanda Senger reflects critically on some of Chika’s insights about the ancient Maya masterpieces on display, her K’iche’ background and the ways she finds to live her cultural heritage abroad.

***

While Chika Cuy and her sweet 8-year-old boy Brandon navigated the city and the messy subway system from far South Brooklyn, I kept imagining them emerging from the mix who were coming and leaving the museum in a flowing rhythm. And just because one waits, the world around suddenly becomes more noticeable. The bright sun rays warm the body, and nurture the thoughts. Unfamiliar languages make the soundscape vibrant and babelian as if a lively preview of the multicultural heritage housed inside the majestic Met building. On view, the exhibition Lives of the Gods: Divinity in Maya art – deemed the first major exhibition of Maya art in a decade, joins this which is one of the world’s largest collections. The curatorial team, led by curator Joanne Pillsbury, associate professor of Anthropology at Yale University Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos, and associate curator Laura Filloy Nadal, present Classic Maya visual culture following the arc of the lives of Maya gods and their place within a cosmological framework. The nature-based gods were depicted by master artists of the Classic period (A.D. 250–900) in different media at all stages of life, dying in tragic situations and some even born anew, providing a model of regeneration and resilience. I cannot help but think of my friend Chika as a model of indigenous migrant resilience as well. Her struggle to live her traditions and practice her art rooted in those ancient values and knowledge in contemporary society also spatially and ethically so distanced from it evokes somehow a Maya historical endurance that has survived centuries of colonial dynamics and still offers a creative and viable way of life capable of subverting migrant marginalization.

My wonders about what Chika’s responses to viewing Maya masterpieces in an U.S. leading art institution will be or what stories from her long-left rural home in Guatemala will be brought about by those curated narratives only stop when she finally arrives with Brandon, and we go to the practical. We take an alternative entrance to avoid the crowds and get our resident tickets. This route has the magical escalator that lands you directly in ancient Greece, some 2300 years ago among marble sculptures and other Greek decorative objects. The spell still works for first-time visitors – Brandon is immediately engrossed by a giant downsized fluted column with foliage carving in the capital while his mother makes a kind of involuntary move out of the main corridor as if called by the small gold jewelry there. After some pictures, we remind ourselves where we’re going to and the focus necessary to resist the enticing time-traveling until we get there. As if taking notes with the eyes for future visits, we cross the Great Hall and reach the second floor where a Jean Charlot’s lithograph stops Chika again. She likes the smooth representation of “the tortilla maker” (1942) explaining the image that certainly touched her deepest memories – “she is grinding corn while carrying her child on her back.” Chika and Brandon exchange some mother-and-child words to make sure they have settled in the new environment and we finally reach the Met’s 999 room, the one that temporarily displays “Lives of the Gods: Divinity in Maya Art.”

Censer stands, Mexico, Chiapas, probably Palenque, ca. 690–720, ceramic-sculpture, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.

Once more, the peppy duo rushes to see the first pieces showcased, a pair of highly-elaborated ceramic censer stands, which at first glance reminded Chika of the “Ja-guar, the nocturnal god that lives in the mountains,” she says creepily. Although the Jaguar is not discernible in the faces depicted in these stands, it is rendered in the one sitting in the next room. These actually “portray gods with both human and animal features wearing tall headdresses of stacked masks.” Nonetheless, as one of the most important deities in the Maya pantheon, the Jaguar god of the underworld certainly would be one of the most revered through the incense and aromatic resins burned in the bowl that would sit atop any of the cylindrical bases. Chika’s reaction to it implies the mysterious atmosphere created in religious rituals, where the smoke curling up into the air was one way to communicate with the gods and beings that were all around in hope to get their blessings.

After this spontaneous encounter, we go back to see the explanatory text on the entry wall. Chika gets emotional when she recognizes the K’iche’ version of the text beside the English and Spanish versions. After being meditatively silent, she starts to share the content of what she is reading in her native language. Her rendering of some terms in Spanish is slightly different from the text on the wall, as it denotes a common issue in translations. For instance, the words noche and día, night and day in English, she translated from K’iche’ as anochecer and amanecer, sunset and sunrise respectively. She then ponders on what she is reading: “That’s true! The Mayas had an explanation for everything in the world. They adored the sunset, the sunrise, the animals, the corn, and gods that we cannot understand. Today, people take sunset and sunrise for granted, for example. But it is not this way; natural forces work for that to happen. Everything in nature has an explanation, and without nature we cannot live. And the Mayas knew all that.” This speaks loudly to the concept of the exhibition itself, to show through the nearly 100 small and monumental works “the world evoked by the Mayas in which the divine, human, and natural realms are interconnected and alive.”

On the other side, Brandon investigates a map of the ancient Maya territories, from the Yucatán peninsula to Guatemalan and Honduran highlands, present-day southeastern Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, and northwestern Honduras. He proudly reads the name of her mother’s home country “GUATEMALA” and says he will visit there when he grows up. Chika points out her hometown Santa Catarina Ixtahuacan near the picturesque Lake Atitlán, surrounded by mountains and volcanoes in the southern state of Sololá. The K’iche’ indigenous people, today’s largest group of the Maya peoples (around six million in total or 9.1% of the 42% Mayas in a population estimate of 17 million Guatemalans), reached the peak of their power in this region during the Maya Postclassic period (c. 950–1539 AD), right after the collapse of the Maya classical city-states showed in the exhibition and until the invasion of the Spaniards in the XVI century. Santa Catarina Ixtahuacan was named in honor of Santa Catalina de Alejandría with Ixtahuacan meaning “plain with a wide view”, as names of Catholic saints with the addition of an indigenous reference was a common combination to name places and indoctrinate people in colonial times. In fact, Chika explains that farming corn, beans, coffee, and vegetables, in those plains, is still the main economic activity of her town, which is divided into caseríos, small community-oriented rural villages that comprise 95% of the municipal territory. There, 94,2% of the around 60.000 population are Maya K’iche, according to the 2019 Guatemalan census. Many of their young people have been emigrating due to a lack of jobs, high levels of poverty, and precarious access to education. Chika noticeably gets a bit nostalgic, since it’s been over a decade that she has not set foot on her land and hugged her parents and loved ones, a stark reality shared with most indigenous migrants that made their way to a “life with more opportunities in the U.S.”

Perhaps it was the rumination of those nostalgic feelings that prompted the sudden and excited question: “Would you like to visit Guatemala? Her unconscious knows that she would be the guide on such a trip and therefore the real inviteé of this kind offer that unfortunately cannot come true soon because of bureaucratic reasons. This thought came about in front of a huge screen showing the Tikal ruins amid overgrown vegetation and surrounding forest, surely a landscape with strong connotations for Chika. “There live the fearsome Jaguar and the Quetzal, the Guatemalan national bird,” she tells Brandon. Chika often embroiders the Quetzal and other Central American birds in decorative pieces and huipiles that she sells in a textile library and collective fairs.

Chika weaving in her home in Brooklyn. Still photo from “K’iche’ Covid vaccine campaign,” Milton Trujillo, Red de Pueblos Trasnacionales, 2022.

She learned to embroider with her mother, a tradition passed down through generations of Central American indigenous women. As a keen observer, young Chika asked her mother many times to embroider until the day that she finally agreed. “My mother has a special relationship with the yarns. She is afraid they can get damaged or damage the eyes of the woman embroidering if the work does not turn out well.” No doubt that Chika mastered her technique with passion and creativity. Not only does she not damage the yarns, but gets the best combinations out of them as if they cooperate with a liveliness that her mother already knew they could do. Furthermore, she said lately that the thousand miles that separate her from her homeland do not prevent her from imagining the song of the birds or the sound of the forest, elements that she captures in her embroidering and that, ultimately, keep her grounded to nature, even though she physically inhabit the polluted New York urban environment.

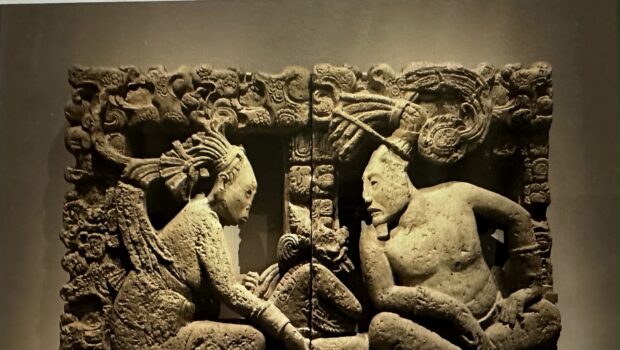

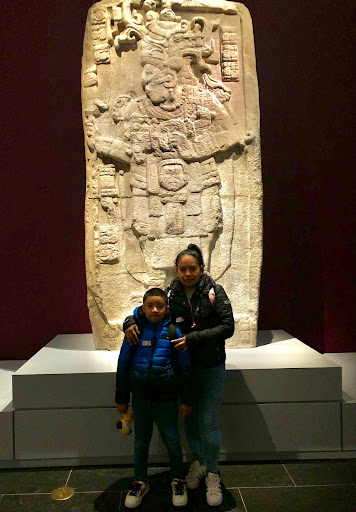

Throne Back, Guatemala or Mexico, Usumacinta region, 7th-9th century, stone-sculpture, Museo Amparo Collection, Puebla, Mexico.

Going through the rhythm of her recollections, and advancing the first section of the exhibit named Creations, the one presenting mythical episodes related to the origin of the world, we stop by a stella taken from the back of a throne from the Usumacinta River area (Guatemala or Mexico, 7th-9th century). Carved in limestone, “a bearded lord and his companion observe a small supernatural creature seated between them,” believed to be “a messenger from the old celestial god Itzamnaaj.” In another interesting personal insight, Chika recognizes the Other in front of her saying “I am not them. We [the modern K’iche’] are different. We have their culture and values, but we are different. We live different lives and look at their physical features, their hair, and eyes. Of course that we are still alike, but we are no longer the Mayas.” Realizing that she is making a powerful statement for herself and who else is interested in her cultural heritage, Chika touches the colonial wound with cool assertiveness. In other words, she acknowledges the violent history endured by her ancestors since the European invasion as a point of no return that provoked a whole reorganization of their social fabric and spiritual lives. She further develops: “For instance, we have now only one God, the Almighty that gives us everything. He allows us to be here, to learn about the culture of our ancestors, our origins.” Indeed, the fact that Chika adores the Catholic God (she attends a Catechism Workshop every Sunday) is in no way seen as a contradiction to the practice and perpetuation of K’iche’ rituals and traditions. After all, it was through that syncretism that previous generations of the Mayas resisted to a complete erasure of their cultures that colonial and neocolonial dynamics never stopped trying to achieve.

Chika’s approach to language, however, is much more purist. She learned Spanish in school, and although she sounds bilingual, she feels she cannot express herself fully in Spanish. Therefore, whenever she encounters a fellow K’iche’ speaker, she is eager to talk to them. But to her surprise, there have been occasions when people from her community in NYC reply in Spanish. Very frustrated, she thinks that this is an incorporated behavior that indigenous migrants bring from home countries, where they might have experienced discrimination and racism due to speaking their indigenous language. Then, in the U.S., “we suffer this prejudice twice because usually we struggle to learn English, since we don’t have too much time and resources to invest in it,” she said. “Instead of giving up our native language, we must speak up! I have lived plenty of experiences that showed me that my language and rich culture are my resistance in this capitalist world. We empower one another when we unite through our language and indigenous cultural heritage.” This is a potent social alternative to counter the neutralizing subjectivity imposed by grueling and alienating working conditions for most immigrants. Chika’s conscious decision to highlight differences (racial, ethnic, class, and gender) works rather to strengthen a solidary oneness capable of freeing individuals to imagine and pursue a life of well-being and self-determination.

These reflections came out of Chika’s disappointment with her inability to read subsequent labels as we progress viewing ceramic vessels and sculptures, an exquisite conch-shell trumpet, jade pendants, and other ornamental objects in the rooms dedicated to Day and Night deities. She wanted to learn more details about the pieces but could only identify K’iche’s words intermingled with her English guesses. In front of another stela depicting a mythological scene, she reads Popol Wuj, recalling vaguely that she had studied the book as a kid aged like her son now. After that early contact, Chika never learned again about the famous Maya text, believed to have been written by a native K’iche’ who had been taught the Latin alphabet in the mid-sixteenth century. The label describes the scene depicted in the stela, “an upended crocodile becomes a lush tree” and “in the right, a figure holds up a vertical element on which a monstrous bird is perched. Perhaps a mythical hero or god, he has lost an arm, likely in confrontation with the bird.”

Stela with mythological scene, Chiapas, Mexico, 300 B.C – A.D. 250, stone, Museo Arqueológico del Soconusco, Tapachula, México, Secretaría de Cultura-Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Remarkably enduring myths like this conflict were part of the origins of the world in which the gods that became the sun and the moon eventually defeated such dim-lighted supernatural creatures. Based on early Maya oral traditions, those understandings of the universe were gathered in the Popol Wuj, an effort to record Maya cosmology and tradition to future generations in face of the destruction of their culture caused by the colonial enterprise. A bit annoyed at depending on others not to miss it all, Chika finally says kind of joking but also acknowledging her right over this knowledge: “They should have translated all the labels into Spanish. And then hire me to translate everything to K’iche’. I know that would be hard work because there are 28 Mayan languages that they could also translate. But the fact is that the information in English does not reach our communities, and that’s why there are no more of us here to enjoy this amazing exhibit.”

In a brief conversation after my visit with Chika, curator Laura Filloy-Nadal enthusiastically welcomed these claims, remarking that it helps to push the ongoing discussion across Met’s curatorial departments in increasing language access through appropriate second-language labels. She also noted that the curatorial team followed current museum policies, providing a handbook with all Spanish transcriptions right in the first room of the exhibition, though it was easily missed during our visit. Regarding strategies used to reach multilingual audiences, she mentioned a schedule of Spanish-guided tours that are put together in partnership with the education department and are still open to book by whoever emails them. It seems just a matter of who takes the first step to bridge linguistic gaps and strengthen connections between such big institutions and local communities. Beyond that, it is imperative that museums recognize broader demands like time constraints and lack of cultural belonging of non-English speakers to expand their role as cultural producers. Not only can they provide transformative learning experiences through innovative approaches of their collections, but conceivably collaborate as catalysts for social change too. People like Chika are pretty open to interacting with new settings in the city, and usually are looking for more integration. Although there are no precise numbers about how many Maya people live in New York or in the U.S more broadly, it would be fair to estimate that they might at least match the percentage in Guatemala itself, if not be higher. “This may be even more the case in NYC, where one of the most concentrated Guatemalan communities lives in Brooklyn and has a substantial K’iche’ component, observed Ross Perlin from Endangered Languages Alliance (ELA). With that said, from the 1.7 million Guatemalans living in the U.S. (Pew Research Center, 2021), almost half of them would have a Maya background and would certainly benefit from better inclusive language initiatives in museums.

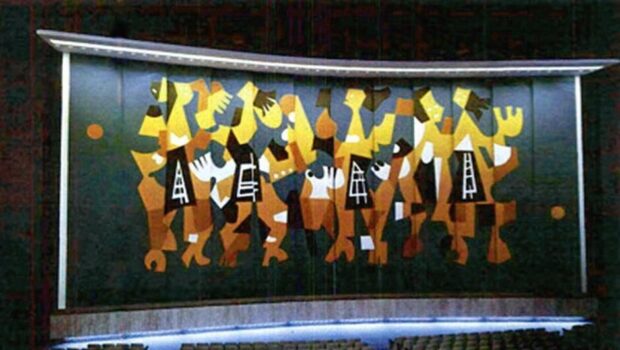

Otherwise pleased with everything we have seen so far, we move faster to the remaining rooms, each also devoted to one or more related deities. In the gallery dedicated to the god of rain and storm Chahk, a combination of sounds of the tropical forest (rainfall, thunders, the wind blowing) in another compelling visualization of Maya highlands successfully evokes an atmosphere in which the objects displayed would have been inspired. They were once more creations of high-skilled elite artists to venerate a moody god that, in this case, could bless with a fertile season or castigate with floodings or severe droughts that would cause famine and violent competition for resources. Walking by the display cases under a psychological sensation of pure air, Chika recognizes what she calls “piedras de rayo” or “lightening rocks” which are flints and obsidian flakes that were all around where she used to walk in the Guatemalan woods. These, however, are skillfully sculpted or have finely incisions with representations of deities or animals that also inhabit those volcanic lands.

View of artworks displayed in the exhibition room dedicated to the Maya god of rain and storms.

Reptile creatures ride a canoe with K’awiil, the lightning god associated with fertilization on the earth. Rabbits known as cunning tricksters and denizens of the moon appear along with the god Maize, a lunar god among other attributions. Hummingbirds, a pelican, jaguars and a baby jaguar, wild pigs and peccaries, a serpent, aquatic creatures with fins, turtles, water lilies and other flowers are part of the non-human Maya repertoire that composes mythological scenes in a variety of ceramic vessels, dishes, bowls and ornaments. Lastly, a well-preserved crocodile painted in luxurious Maya blue that served both as a whistle and a rattle amuses young Brandon and advances the beautiful air whistles placed in the next room, which is dedicated largely to the god Maize.

The artist Chika Cuy says proudly “I am always looking for inspiration for my embroidery in my ancient culture.”

Chika takes pictures of some hieroglyphs as inspiration for her embroidering while Brandon moves around to see miniatures of the god Maize. In a triad of delicate ceramic whistles sculptures, the god of corn and harvest protector comes out of a cob as a symbol of eternal regeneration or blossoms from a flower in an equal reference to his power of resurgence after death. Central to Maya communities, corn is also the raw material in which the gods created intelligent humans capable of worshiping them properly, after two frustrated attempts through clay and wood that resulted in creatures that could not speak or recognize them.

Miniature ceramic whistles painted with Maya blue pigment would possibly produce sounds similar to birds, 7th-9th century.

Curator Joanne Pillsbury remarked that, unlike other gods, the Maize god is often portrayed as a young, handsome figure with a corn-elongated-shaped head and abundant jewelry or even as a child, which suggests the constant attention and care he would demand to prosper and bless his worshipers across Maya lands.

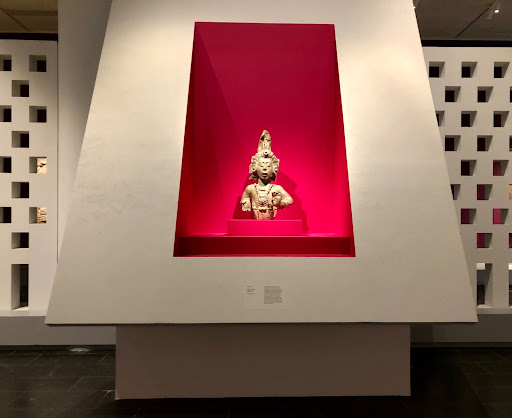

Maize god, Copán, Honduras, limestone, on loan from the British Museum, London.

A bust of him placed in a wall niche, likely to echo his original place adorning the temple of Copán along with dozen others, reminds Chika of a piece her father found plowing the earth, and he keeps home. “In Guatemala, people display found objects like this or enjoy outdoor ruins because the museums are far away in the big cities.” At this moment, the question about the provenance of pieces arises. We learn that the Maize bust traveled from the British Museum, one of the Maize miniatures came from The Museum of Fine Arts (Houston, TX), and the others are from the Brooklyn Museum and The Met’s own collection, respectively. Indeed, the show is outstanding in its assemblage of loans from European, Central American, and other U.S. institutions in addition to the Met’s pieces. Although very impressed with the research and logistics involved in it all coming together, Chika is still not satisfied with the information that we got on-site. She wants to know how those objects made their way into international art collections. Ultimately, she agrees that for a matter of space and synthesis, it is reasonable that we can find more through The Met digital resources. For example, the Maize bust was excavated by the English diplomat and archaeologist Alfred Percival Maudslay in 1884, and finally transferred to the British Museum in 1893. As for the miniature sculptures, each with its own provenance history being one found in a burial site near Campeche (MX) and the others sold many times to private collectors until they were donated to their current museum homes. Figuring out that the traces of colonial history encompassing the material culture are the same endured by humans and the land, Chika concludes with resignation: “All right. I am glad that they are well-conserved, although outside of Maya territories. After all, I love that people get to know my culture. I like to learn about other cultures too. We need to show our diverse cultures and practice them in order to revitalize them. And this exhibition contributes to it.”

In the last part of the exhibition, little Brandon takes the lead. In a corner dedicated to Chuwen, the patron god of scribes and artists, some stone carved glyphs give an idea of the Maya sophisticated hieroglyphic writing system. Then, he points excitedly to a lidded funerary vessel, very similar to the tetrapod bowls he was following in each room. This has a figure believed to be a monkey in the top holder in reference to a deceased scribe or Chuwen himself and still contains food remains prepared for consumption in the afterlife. Brandon agreed that it should be fun to have a meal out of a fancy bowl like this, although he is not a fan of Guatemalan food. “I would have pizza, Chinese food or sushi,” he says. His older brother Gary, 19 now, has recently come to live with them and would love to have Guatemalan food. “I cook tamales and sopita for Gary and speak K’iche’ with him while for Brandon I can teach traditional songs and dance. My children were born in different countries and I try to respect it while I also hope that they love their culture as much as I do,” Chika reflects on the job of raising two children as an immigrant single mother.

Vessel with Scribe, Campeche, Mexico, 4th–5th century, ceramic, Museo Arqueológico del Soconusco, Tapachula, México, Secretaría de Cultura-Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

From the left, Brandon and his mother Chika Cuy dancing with friends around incense burning and ofrendas in a K’iche’ performance ritual, part of the New York Tlán festival in Queens, New York City last October.

Grabbed by hand, we go with Brandon to watch a contemporary ritual performance by Poqomchi’ Maya dancers of the town of Santa Cruz Verapaz, Guatemala. On screen, they perform The Dance of the Macaws, a story that “re-enact episodes from a deep rooted myth that explains the origins of social institutions and the worship of the gods” through a dispute between parents, daughter and an invader soldier. Brandon tells me that he also dances with her mother and friends. He gets surprised when I reveal that I once saw them dancing and then thought of them when I watched this video for the first time. Chika explains that there are numerous dancing rituals and mythical stories according to each community’s (casaríos) own traditions. “As our ancestors, all of them still use the smoke of burning incense for protection,” she adds. Food and drink, prayer, music and dance are also offered (ofrendas) to nourish the gods, appease them, and encourage them to grant their favors. Once more she stresses the importance of maintaining Maya ancestral traditions and showing her culture to others. “I keep doing this [the Maya dancing rituals] where I live because I don’t want it to die. It was what our grandfathers and grandmothers needed, what they expressed through their culture and understanding of their world.” Even though Chika’s needs are others, her place in the world is in between borders and the place of her children are in between cultures and nationalities, she encounters in her Maya heritage the strengths and practical tools she needs to create a promising future for her and her family.

Chika shifted careers from a bilingual elementary school teacher in Guatemala to a weaver artist in the U.S. Next fall, she will attend university in a program to improve her English and then pursue a fashion degree that she hopes will open doors to her art and business. With the eye trained to “always look for inspiration in [her] culture,” she spots textile patterns carved out of a royal woman’s huipil in a mid-sized stela in the last section dedicated to Patron Gods. It fulfills in part her expectations to see traditional textile outfits displayed but also made her resonate that the materiality of organic yarns would not survive all the way from the Maya classic period. She asserts: “You see, to preserve the rich weaving knowledge has been the job of generations of K’iche’ women, myself included. Worryingly, Guatemalan schools do not teach it and, since women do a lot of other modern jobs now, many do not have time to learn the painstaking labor of traditional weaving and embroidery.” She also makes sure to clarify that she only does not wear her traditional outfit when the weather is too cold. And maybe influenced by the surrounding monuments of powerful Maya rulers, specially the royal woman stela, she briefly touches the controversial subject of politics to wrap up: “if people gave a chance voting for Indigenous candidates, better indigenous women candidates, conditions would be drastically different for indigenous peoples to flourish in whatever they feel inspired to do without to be forced to leave their homes or the place they want to live. But while it does not happen, I am grateful for what I can accomplish with my life and art. I have found opportunities to live well, learn about other cultures, value and show mine wherever I go, unfortunately, except back home.

Fernanda Senger holds a B.A. in History from Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Brazil. In New York City, she has worked with Red de Pueblos Trasnacionales, where she met Indigenous migrants from several ethnic groups of present-day Mexico and Guatemala. She has also collaborated with Huellas Magazine.

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

Posted: April 13, 2023 at 8:50 pm