THE SELECTED POETRY OF GABRIEL ZAID. A Bilingual Collection

EL PEQUEÑO LIBRO AZUL

Sven Birkerts

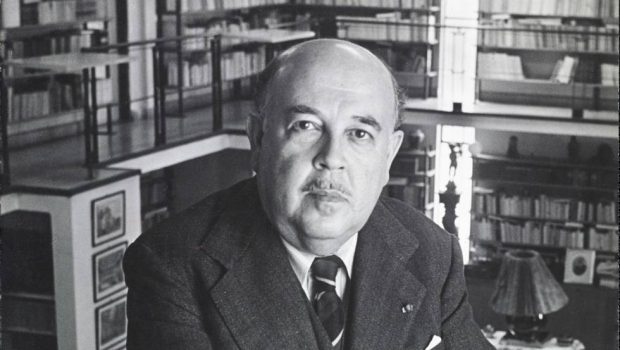

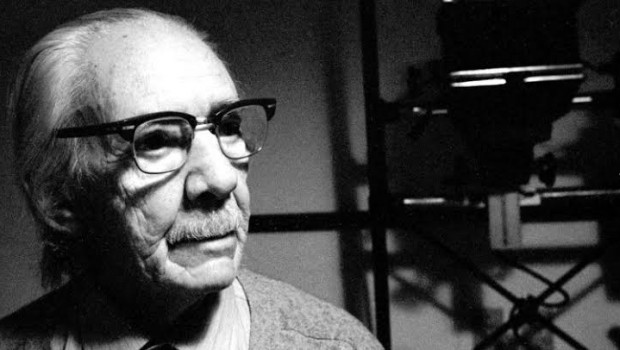

The gates of the Garden of Information have been thrown wide open and there is no keeping up. This might be an ongoing consequence of our original eating of the Tree of Knowledge—along with mortality. I have been among books for most of my life, but I did not know about Gabriel Zaid until I was asked if I would review a book of his translated poems. I said yes, believing that such invitations are often providential. I enjoy responding to writers about whom I have no preconceptions whatsoever. And so when the small blue book arrived in the mail, I deliberately gave it a most cursory once-over, checking out the cover and copyright page, looking past the introduction by Octavio Paz, and then, when a moment right for poetry came, I settled in to read.

I went cover to cover in one sitting. The book is short, as are the poems. And I found I was able to read in that almost completely de-contextualized way that is so rare. For I did not know the man’s position (though I reckoned it must be estimable if Octavio had written the introduction), his other work, his life circumstance—anything. Just these poems on the page, filtered down from Spanish into English by various translators.

The news was just that–fresh off the press, as it were.

Zaid, on the page, is an ecstatic. A metaphysician. He appears to be, in the phrase of Blaise Cendrars, an “astonished man,” seeing as if anew. He expresses his surprise at nature, at being in the midst of being by way of compressed images that, as they reach us, convey the soul’s double-take—and this, I think, can only come from a certain estrangement. The making of such images is an alienation looking to repair itself. An example:

An Abandoned Nocturne *

The secret unsettling

that a fallen leaf

leaves lightly in the air

reaches me.

The inert lucidity

of the deserted park,

the water raving on

in the sleepless fountain.

But you exist no less, communion,

and touch us, intimately,

in words that lead the warp

through the woof of the world.

Part of the charm—and power—of this little poem lies in the fact that we cannot lock it up completely. The suggestions stir us, pull us toward contemplation, but they do not issue in anything we can reliably summarize. “Where there is amenability to paraphrase,” wrote Mandelstam, “there poetry has not spent the night,” and the phrase is apt to Zaid’s work.

The poem reaches us first through its verbs, its depictions of movement. The motion of the falling leaf, which we naturally picture not as a vertical drop so much as a sketchy sashaying. The water in the fountain—not purling, but raving–gives us the sense of an agitation that amplifies the “unsettling” left on the air by the leaf. And then the complex action of the third stanza: “communion” described as an intimate touching, followed by the action of words leading “the warp/through the woof of the world.” We figure the image in our minds; we catch the visual echo between that swaying of the falling leaf and the interweaving of warp and woof. The first—leaf—is downward, the seasonal emblem of dying, whereas the communion, and the words binding to the world, are renewing and redeeming. Does Zaid intend any religious implication? Or are we to take it as the self joining the world, entering its otherness by way of language? Can the two senses co-exist? Why not? The poem—like so many of the others—leaves us tipped off our center of balance, wobbling on our axis.

Take another.

Get-Away *

Cut loose the basket.

Let fly the balloons full of kisses.

There goes the world, falling behind.

And the depths in the eyes causes vertigo.

Get screwed in tight.

Let the wind take you.

Cast off the slack, jettison the sand.

Already you’re out into space beyond time.

This is different. Eight lines, each a sentence (in the Spanish as well). The mode is imperative. A set of commands relating, on the face of it, to taking off from earth in an air balloon. But there is that word “kisses” in the second line—warrant, along with the later “depths in the eyes causes vertigo,” to consider all of the injunctions as relating to love, to the letting go of the self in the presence of another. Is this addressed to the world at large, to another person, or is it self-address? We don’t know. And I’m not sure it matters. What matters is the directional velocity, the feeling of a translation across boundaries, into a new state, whether this is conceived physically, emotionally, or metaphysically.

Again, as with An Abandoned Nocturne, the meanings are driven by the juxtapositions of the various verbs and their actions. If the fist verb is an active imperative—“Cut”—the actions of the seven remaining lines are in one way or another passive, representing one or another kind of giving over, making the poem’s decisive moment, in a sense, its first word. But the action is not completely one-directional. The initial sense of fast upward momentum is countered, stalled for a moment, by the shift in line four. Where it had been the world falling away in the previous line, now it is the image of the depths of a pair of eyes—eyes looked into—which causes a sensation of vertigo, commonly understood as dizzy and downward sensation. The checking motion only amplifies the sense of release, and of ultimate attainment when the bonds of space/time have at last been broken.

All of this is compressed into eight short and relatively simple lines. It is, if I can generalize, Zaid’s mode, or, to abbreviate, his M.O. The subject matters of the 42 poems in this collection vary—some are more lyric, others more spiritual, and still others satiric—but their procedure is recognizably that of a single sensibility. Here is a poet who favors both simple imagistic compression, using for his images mainly the materials of the natural order (though here and there an automobile or an elevator will appear), and the dynamic expansions and shifts of perspective made possible by inventive juxtapositions. The final effect, of the individual poems as well as of the book, is of an outward movement, at times that of slow natural growth and at other times of explosion. It is a momentum of possibility, opening out. Into ____?

When I had finished reading and pondering, I turned to see what Octavio Paz had written (in Cambridge, Massachusetts) in 1976—just down the road from where I am now, but nearly 40 years ago. Paz made as good deal of Zaid’s importance as an intellectual figure, a critic; he noted, too, that he is a Christian, but one whose spiritual inquiry and affinity connects him to other beliefs (Neoplatonism, Buddhism…). Most interesting to me, he characterized the poetry as occupied with estrangement and the feeling of the “other,” those late-century conditions. But then he went on to observe—and I feel I should give the last word to him, for he has captured it with his characteristic gracious command: “Time, presence, death: love. Zaid is a religious and metaphysical poet, but also—or rather therefore—a poet of love. In his love poems, poetry functions once again as a force with the power to transfigure reality.”

As I wrote, I had not known Zaid—but as his poetry has confirmed for me, we live by moving forward, enlarging our compass.

Sven Birkerts is editor of the journal AGNI. He will publish his tenth book next year with Graywolf Press.

*Translated by George McWhirter

Traducción de David Medina Portillo

Las puertas del Jardín de la Información se nos han abierto de par en par y sin custodia alguna. Esto podría ser todavía consecuencia de cuando probamos el fruto del árbol del conocimiento... y de nuestra condición mortal. La mayor parte de mi vida he vivido entre libros pero sin saber nada acerca de Gabriel Zaid, hasta que me preguntaron si me gustaría comentar un libro con sus poemas traducidos. Acepté creyendo que, con frecuencia, tales invitaciones resultan providenciales. Me gusta ocuparme de escritores sobre quienes no tengo ideas preconcebidas de ningún tipo. Así que cuando este pequeño libro azul me llegó por correo, deliberadamente le di un vistazo somero a la portada y la página legal, obviando la introducción de Octavio Paz y, más tarde, cuando llegó el momento idóneo para la poesía, me instalé a leer.

Lo leí de un tirón de la primera a la última página. El libro es corto, como los poemas. Y descubrí que era capaz de leer de esa manera tan infrecuente que consiste en hacerlo casi al margen de cualquier contexto. No sabía nada del autor (aunque supuse que debía ser estimable puesto que Octavio había escrito la introducción), ni de su trabajo ni de las circunstancias de su vida. Sólo tenía estos poemas sobre la página, filtrados del español al inglés por varios traductores.

La noticia no era más que eso: un libro recién salido de las prensas, por así decirlo.

Zaid, un metafísico, se extasía sobre la página. Al parecer, y en palabras de Blaise Cendrars, es “un hombre asombrado”, como si viera todo de nueva cuenta. Expresa su sorpresa ante la naturaleza, la plenitud del ser, mediante imágenes sintéticas que, tal y como llegan a nosotros, transmiten esa “doble visión” del alma –y esto, pienso, sólo puede provenir de un cierto alejamiento. La creación de tales imágenes es un distanciamiento que busca repararse a sí mismo. Un ejemplo:

Nocturno abandonado Me llega la secreta zozobra que en el aire deja ligeramente una hoja caída. La lucidez inerte del parque abandonado: el agua que delira en la fuente sonámbula. Y sin embargo existes, comunión, y nos mueves en íntimas palabras que entretejen el mundo.Parte del encanto –y del poder– de este pequeño poema radica en el hecho de que no podemos cerrarlo por completo. Las sugerencias nos incitan, nos empujan a la contemplación pero sin emitir nada que podamos concluir confiadamente. Mandelstam escribió que “donde hay disponibilidad a la paráfrais, la poesía no ha pasado la noche”. Y su frase viene a cuento si se habla de la obra de Zaid.

El poema nos llega sobre todo por sus verbos, sus imágenes de movimiento. El desplazamiento descendente de la hoja que, naturalmente, imaginamos no como una caída vertical sino como un baile impreciso. El agua en la fuente –no la que la orla, sino delirante– nos evoca una agitación que amplifica el inquietante dejo de la hoja en el aire. Y después la compleja acción de la tercera estrofa: la “comunión” descrita como un contacto íntimo, seguido por la acción de las palabras que enlazan la urdimbre, “íntimas palabras/ que entretejen el mundo”.

Nuestra mente se figura todo aquello; captamos el eco visual entre el vaivén de la hoja que cae y la superposición de urdimbre y trama. La primera –la hoja– es descendente, emblema estacional del morir, mientras que la comunión, y las palabras que atan al mundo, son de renovación y redención. ¿Hay en Zaid una intención religiosa? ¿O debemos tomarlo como el acto del ser que se religa con el mundo o ingresa en su alteridad por medio del lenguaje? ¿Pueden coexistir ambos sentidos? ¿Por qué no? El poema nos deja como en vilo, vacilantes sobre nuestro eje.

Tomemos otro ejemplo:

Evasión Desatar la canastilla. Subir globos llenos de besos. Ya va quedando el mundo atrás. El fondo de los ojos da vértigo. Cogerse desesperadamente. Ser arrastrados por el viento. Soltar arena, perder peso. Ya estás en el espacio sin tiempo.Esto es diferente. Ocho versos, una sentencia cada uno (tanto en español como en inglés). El modo es imperativo. Un conjunto de órdenes relacionadas, a primera vista, con el ascenso de un globo. Pero la palabra “besos” de la segunda línea autoriza, junto con la siguiente “El fondo de los ojos da vértigo”, a considerar todas las órdenes como relativas al amor, al dejarse ir en presencia del otro. ¿Todo esto se dirige al mundo en general, a otra persona o a sí mismo? No lo sabemos. Y no estoy seguro de que ello importe. El toque está en la velocidad direccional, la sensación de desplazarse más allá de los límites y hacia un nuevo estado físico, emocional o metafísico.

Aquí, como en “Nocturno abandonado”, los significados se rigen por las yuxtaposiciones de los diversos verbos y sus acciones. Si el primero de éstos es un imperativo activo –“Desatar”–, las acciones de los siete versos restantes están en una u otra forma pasiva, representando cierto tipo de inmovilización, por lo que el momento decisivo del poema se halla, en cierto sentido, en su primera palabra. Aunque la acción no es completamente unidireccional. La sensación inicial de un rápido impulso hacia arriba, suspendida por un momento, se contrarresta con el cambio en la cuarta línea. El mundo cayendo de la línea anterior ha sido desplazado por la imagen de un par de ojos –ojos examinados– cuyas profundidades provocan una sensación de vértigo experimentado habitualmente como mareo. El ademán de escrutinio sólo amplifica la sensación de alivio y logro cuando los lazos de espacio/tiempo ya se han roto.

Todo esto se comprime en ocho líneas cortas y relativamente simples. Tal es, si puedo generalizar, el estilo de Zaid o, para abreviar, su modus operandi. Los temas de los 42 poemas de esta reunión varían –algunos son más líricos, otros más espirituales o satíricos–, pero su procedimiento es reconocible como el de una sensibilidad única. Un poeta que favorece tanto la síntesis imaginista –utilizando para sus imágenes sobre todo materiales de orden natural (aunque aquí y allá aparezcan un automóvil o un ascensor)– lo mismo que ampliaciones y cambios dinámicos de perspectiva gracias a sus inventivas yuxtaposiciones. El efecto final, tanto de cada poema como del libro en su conjunto, es el de un movimiento hacia fuera, en ocasiones el de un crecimiento natural lento y, en otras, como el de una explosión. Se trata de un momentum de posibilidades, de apertura. ¿Hacia ____?

Sólo cuando terminé de leer y reflexionar, volví sobre mis pasos para ver lo que había escrito Octavio Paz en 1976 en Cambridge, Massachusetts, justo al final de la calle donde estoy ahora, aunque casi 40 años atrás. Paz destaca la importancia de Zaid como figura intelectual, un crítico; señala, asimismo, que es un cristiano cuya inquietud espiritual y afinidad se conectan con otras creencias (neoplatonismo, budismo...). Y lo más interesante para mí: ve esta poesía tanto ocupada por un distanciamiento como por un sentimiento de los “otros”, condiciones ambas de finales de su siglo. Pero entonces llega a observar –y creo que debo darle la última palabra, porque él lo ha capturado con su gracia característica: “Tiempo, presencia, muerte: amor. Poeta religioso y metafísico, Zaid es también –y por eso mismo– poeta del amor. En sus poemas amorosos la poesía opera de nuevo como una potencia transfiguradora de la realidad”.

Como empecé diciendo, nada sabía de Zaid; pero según me lo ha confirmado su poesía, vivimos para avanzar ampliando siempre nuestros horizontes.

• Sven Birkerts es editor de la revista AGNI. Su décimo libro aparecerá el próximo año bajo el sello de Graywolf Press.

Como podria proponer para publicacion en Literal la poesia mas reciente del poeta cubano Jorge Enrique Gonzalez Pacheco, poeta reconocido internacionalmente.

Gracias,

JM

It is not my first time to pay a visit this web site and it´s wonderful to get to know new authors