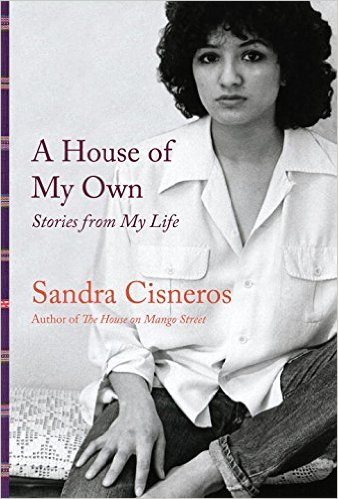

A House of My Own: Stories from My Life

David D. Medina

Virginia Woolf needed a room of her own in which to write. Sandra Cisneros needed a house, a silent house that would offer a space to imagine, to think, to be alone, and to create. She longed for a place that would provide protection while she struggled to invent herself as the artist she wanted to become.

“All my life I’ve dreamt and dream about a house the way some women dream of husbands,” she writes in her new book, A House of My Own: Stories from My Life. That desire for a house is the overriding theme in this collection of more than 40 pieces that appeared between 1984 and 2014 in a variety of publications.

“Rather than write an autobiography, which I have no inclination to do at the moment, a form of weaving one’s own death shroud,” she explains, “I offer my personal stories as a way of documenting my own life.”

The stories range in theme, from her childhood memories of growing up in Chicago, to writing her first book, to writers and artists who have influenced her writing, to the Virgin Mary and a treatise on sexuality, to tender and honest accounts of her mother and father. Almost each page comes laced with Cisneros’ fierce determination to assert herself as an independent woman and a defender of the Latino culture and the oppressed. Tough as that may sound, anger doesn’t flow in her stories. Cisneros believes that an idea for a story might begin in rage, but the final version should end in beauty.

Her first beauty in the collection is “Hydra House,” a story that narrates the time she spent writing her first book on a Greek island, which she describes as “a paradise absent of automobiles” filled with “a cascade of stone houses.” She rented a small, primitive, whitewashed house above the village with a view of the sea and a blue sky. The simple structure inspired her to write. She wrote every day, first in longhand, and then typed what she had written, made corrections, and then retyped the corrections. From midday to sunset, she wrote, living like a monk during the day and a loose woman at night. “It was in a way an ideal life,” she recalls. “A cloistered convent in the day and the Pirate Bar at night.”

This process worked. While on the island, she completed her best book to date, The House on Mango Street, which catapulted her into the pantheon of award-winning authors and eventually into many fellowships, including the Dobie-Paisano and the MacArthur, and drew her into lectures and workshops around the world. Then came the prize: The book’s success generated enough money to allow her to buy a house in San Antonio.

Cisneros may have written her book in a relatively short time, but the incubation period was a lot longer—like her whole life. The setting and many of the characters are based on people she met while growing up in a Mexican-American neighborhood in Chicago. Her father was an upholsterer and her mother a homemaker, who had to care for six sons and a daughter. Cisneros attended Loyola University Chicago and the Iowa’s Writers Workshop, and then taught high-school dropouts before she could find her own voice. She found it by studying other writers, such as Jorge Luis Borges. According to Cisneros, the stories in Borges’ book, Dream Tigers, read like fables written with lyricism and succinct poetry. “I only want to say that it was Dream Tigers that gave me permission to dream in the same way that Kafka gave Gabriel Garcia Marquez permission to dream,” she writes.

Her life is split between two cultures: the American and the Mexican. Her writing reflects that tension. Succinct and poetic, her writing combines low art with high art, a cliché with a fresh image, fragmented phrases with elegant sentences, curanderas (healers) with intellectuals. Cisneros’ writing, as well as her life, is an inspiration to all—men and women—who desire to write but must find a place of their own to create.

David D. Medina is a literary critic and a director in the Office of Public Affairs at Rice University

David D. Medina is a literary critic and a director in the Office of Public Affairs at Rice University

Posted: August 31, 2015 at 7:47 pm