Hélio Oiticica: Enthalphy and Entropy

Entalpia y entropía

Fernando Castro

Hélio Oiticica’s current exhibit The Body of Color at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston may tempt the viewer to agree with writers who have called his art “ordered delirium.”1 On the one hand there is forethought and calculation; on the other, spontaneity and a crescendo of forms and colors (pink, yellow, orange, red, etc.) incarnated in a variety of objects. Many of these objects escape known art genres and fall into new categories

invented by Oiticica in the sixties. In the midst of this genre confusion the run-of-the-mill viewer may find it a little harder to fathom order. Oiticica’s order mirrors Rio de Janeiro’s popular culture and the organization within the seemingly chaotic constructions of the favelas.

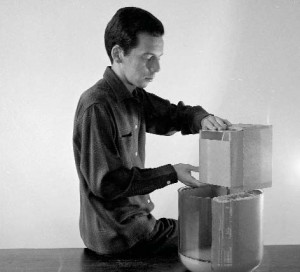

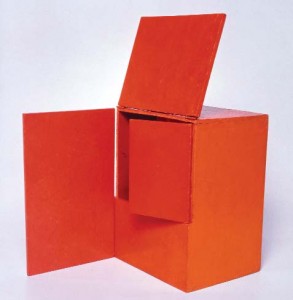

The bólides caixas are peculiar boxes that fold, have drawers, hold pigments, pebbles, shells, mirrors or photographs.

Often they are made of materials picked from the street and painted in bright yellow, orange, pink or red.

The Body of Color echoes Oiticica’s 1965 exhibit Opinao 65 at the Museu de Arte Moderna (Rio de Janeiro) to which he invited dancers from the Mangueira samba school to participate.2 Writer Anna Dezeuze notes, “The irruption of the poor into the bourgeois atmosphere of the museum caused such a scandal that the director had them evicted. As censorship worsened in Brazil during the later 1960s, Oiticica’s association with Mangueira would increasingly be linked to a political resistance to the dictatorship that had taken over the country in 1964.”3 So what may appear forty-one years later as mere exercises in the formal and conceptual possibilities of art is rooted not only in carioca culture but also in a philosophy of art as a tool for revolution—if not political, at least of cultural consciousness. Oiticica’s gesture towards his working-class friends of Mangueira, barely a year after leftist president Joao Goulart was ousted by a right-wing military coup was not only provocative but also dangerous. The military regime was marked by the torture, imprisonment, murder and disappearance of many politicians, students, writers, and artists.4

There is also an art/cultural background for Oiticica’s work. In 1950 Swiss artist Max Bill, the professed apostle of Concrete art, had exhibited at the recently inaugurated Museu de Arte of Sao Paulo and the following year he won an important award at the first Sao Paulo Biennial. According to Edward J. Sullivan, Max Bill “inspired many younger artists in Brazil to work in a style related to his.”5 The term “Concrete art” comes from Theo Van Doesburg’s Manifesto of Concrete Art (1930). The main tenet of this type of artistic practice was to create works that were “objective” and independent from any symbolism or observed reality. In essence, it aimed to create non-figurative art that did not denote anything but itself. These artistic ideas found fertile ground in Brazil as they coincided with the prevailing ideas of industrialization and architectural renovation. As a result two enclaves of Concrete art appeared in Brazil. In Sao Paulo the Grupo Ruptura was formed in 1952. Among others, it included Waldemar

Cordeiro, Luís Sacilotto, Geraldo de Barros, and Anatol Wladislaw. In Rio de Janeiro the Grupo Frente consolidated around abstract artist Ivan Serpa with an exhibition at the IBEU gallery (1954). At the end of two years the group included Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape, Décio Vieira, the brothers César and Hélio Oiticica, Franz Weissman, Abraham Palatnik, and other poets and artists.

Given the very different cultures of Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, Ruptura and Frente were bound to collide. On the occasion of the 1ª Exposição Nacional de Arte Concreta that opened in Sao Paulo in 1956, members of Ruptura criticized the Frente artists for their lack of structural rigor and for allowing lyrical expression to contaminate their Concrete art. The strict abidance of the Ruptura group to the principles of international

Concrete art was too confining for the more eclectic Frente group. The schism led Ferreira Gullar to write the Manifesto Neoconcreto (1959) for the 1ª Exposição de Arte Neoconcreta at the Museu de Arte Moderna in Rio de Janeiro. In it Gullar objected to the “dangerous rationalistic extremism” of Concrete art and proposed to restore to art its existential, emotive and affective dimension. Moreover, coming close to what Oiticica would later envision, Gullar articulated the idea that “we do not conceive a work of art as a “machine” nor an “object” but as a quasi-body.” To emphasize the Neoconcrete openness, Gullar stressed that Neoconcrete artists did not constitute a “grupo” ruled by dogmatic principles. Eventually the Neoconcrete affiliates would include Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape, Amílcar de Castro, Franz Weissmann, Sergio Camargo, Ferreira Gullar, Aluísio Carvão, Décio Vieira, Hélio Oiticica, Hércules Barsotti, Willys de Castro, etc. Some, like Clark, Pape and Oiticica underscored the importance of dynamism and an interactive physical engagement between works of art and its public.

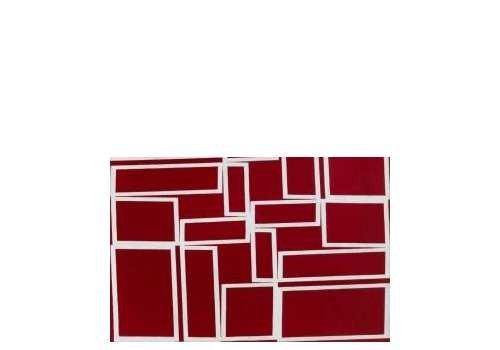

The name of Helio Oiticica’s current exhibit The Body of Color comes from one of his own lucid reflections. “Color,” he stated, “tends to ‘in-corporate’ itself; it becomes temporal, creates its own structure, so the work then becomes the ‘body of color.” This exhibit covers Oiticica’s production from the late fifties to the late seventies. In his late fifties work Eschemas the viewer faces works in which color, movement and form follow the directives of Brazilian Concrete art. They are non-figurative, geometric and made to hang from the wall. It is with his “Relevos” that Oiticica begins the liberation of color from its rectangular bi-dimensional existence. The Relevos resemble colorful origami hanging in space: geometric and minimally volumetric—hence the name that means bas-reliefs.

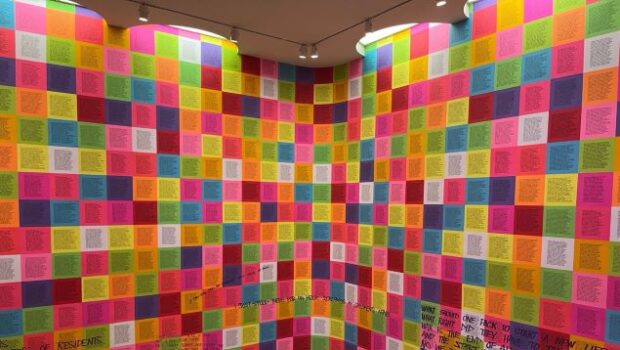

In the inventory of Oiticica’s oeuvre three types of objects figure prominently: bólides, penetráveis, and parangolés. For Oiticica, the bólides (Portuguese for “fast-moving fireballs”) reflected the colors and structures of the favelas. The bólides caixas are peculiar boxes that fold, have drawers, hold pigments, pebbles, shells, mirrors or photographs. Often they are made of materials picked from the street and painted in bright yellow, orange, pink or red. There are also bólides de vidro, like one made of a glass cylinder filled with pink pigment and an embedded cube. Ultimately these “fireballs” set Oiticica’s work apart from the tenet of Concrete art that precluded representation. The bólides are concrete objects that represent, albeit not by resemblance, but by being samples of urban structures and debris.

In the inventory of Oiticica’s oeuvre three types of objects figure prominently: bólides, penetráveis, and parangolés. For Oiticica, the bólides (Portuguese for “fast-moving fireballs”) reflected the colors and structures of the favelas. The bólides caixas are peculiar boxes that fold, have drawers, hold pigments, pebbles, shells, mirrors or photographs. Often they are made of materials picked from the street and painted in bright yellow, orange, pink or red. There are also bólides de vidro, like one made of a glass cylinder filled with pink pigment and an embedded cube. Ultimately these “fireballs” set Oiticica’s work apart from the tenet of Concrete art that precluded representation. The bólides are concrete objects that represent, albeit not by resemblance, but by being samples of urban structures and debris.

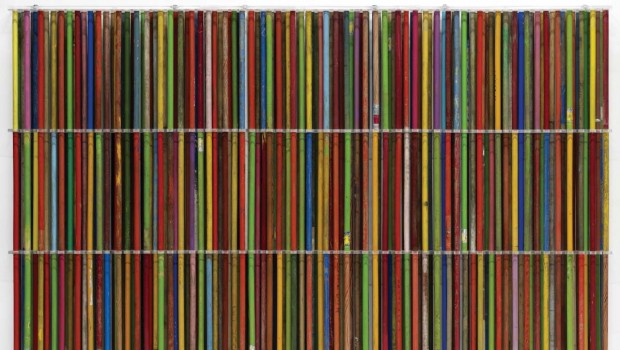

In November 1964, Oiticica wrote: “The discovery of that which I call ‘parangolé’ (slang for a situation of sudden confusion or excitement), marks a decisive point and defines a specific position in the theoretical development of my entire experience with the question of three-dimensional color construction.” The parangolé is a kind of cape, banner or even tent made of fabric, paper, plastic, straw, and/or rope sewn together and painted or drawn. The parangolés were inspired by the capes worn by the dancers of the Mangueira samba school to which Oiticica belonged. The most important conceptual aspect of these works is that they are art to be worn. It is the viewer participation that gives these moving sculptures their changing forms and by wearing them the former becomes an active part of the work.

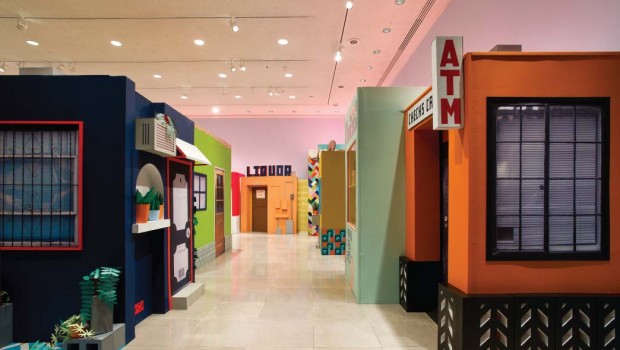

The interactivity of art is a central ingredient of Oiticica’s penetráveis as well. These are works of art to be inhabited (penetrated) just as the parangolés are to be worn. As the participants move inside a penetravel from one enclosure to the next they experience different sensations and feelings. Often the constructions resemble the improvised dwellings of the favelas where curtains or straw mats often take the place of walls, and bedrooms are often little more than boxes. Oiticica invited viewers to take off their shoes and inhabit these spaces through leisure activities such as lying down. The first of these environmental works, “Tropicália,” was mounted at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro in 1967. It became a seminal work that gave rise in Brazil to the Tropicalist movement in all the arts: theater, cinema, poetry, visual arts and popular music.

Aristotle understood that philosophy began with otium —a word that is the root of the Spanish word ocio—meaning leisure time. In other words, if you do not have leisure time because you have to attend to your business (neg-ocio = negation of ocio), you cannot possibly dedicate yourself to philosophical pursuits. Similarly, Oiticica invented the neologism “crelazer” which meant “to believe in leisure.” For him crelazer was based on joy and phenomenological knowledge and was a precondition for creativity. Not unlike Aldous Huxley and Timothy Leary, Oiticica also believed in expanding perception in order to unleash the creative self; he called it the “Supra-sensorial.” The Supra-sensorial could be achieved by hallucinogenic states, religious trance and the kind of delirium reached during samba dance. In his own words, “This entire experience into which art flows, the issue of liberty itself, of the expansion of the individual’s consciousness, of the return to myth, the rediscovery of rhythm, dance, the body, the senses, which finally are what we have as weapons of direct, perceptual, participatory knowledge… is revolutionary in the total sense of behavior.

NOTES

1. The MFAH‘s Latin American art curator, Mari Carmen Ramírez, is a co-author of a soon-to-be-released book The Body of Color—the same name as this exhibit. That is why although there are no curatorial credits at the exhibition or in the MFAH ‘s website—, we are led to believe that she is the curator of the The Body of Color.

2. Hélio Oiticica’s grandfather was anarchist. His father, José Oiticica, wrote the book Anarchism Within Everyone’s Reach (1945).

3. Anna Dezeuze, “Tactile dematerialization, sensory politics: Helio Oiticica’s Parangoles.” Art Journal. Summer, 2004.

4. Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture. Edited by Barbara Tenenbaum, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1996.

5. Brazil: Body and Soul. Edited by Edward J. Sullivan. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2002.

La exposición El cuerpo del color de Hélio Oiticica en el Museum of Fine Arts Houston1 podría llevar al espectador a ver su arte como el “delirio ordenado” que algunos comentaristas describen. Por un lado hay meditación y cálculo; por otro, espontaneidad y un crescendo de formas y colores (rosado, amarillo, anaranjado, rojo, etc.) encarnados en una diversidad de objetos. Muchos de éstos no calzan dentro de géneros artísticos tradicionales sino que pertenecen a nuevas categorías inventadas por Oiticica en los sesenta. En medio de esta confusión de géneros, al espectador común y silvestre le podría resultar difícil hallar orden. El orden de Oiticica es un reflejo de la cultura popular de Río de Janeiro y la organización de las aparentemente caóticas construcciones de las favelas.

En medio de esta confusión de géneros, al espectador común y silvestre le podría resultar difícil hallar orden. El orden de Oiticica es un reflejo de la cultura popular de Rio de Janeiro y la organización de las aparentemente caóticas construcciones de las favelas.

El cuerpo del color hace eco de la exposición Opinao 65 de Oiticica en el Museu de Arte Moderna (Río de Janeiro) a la cual él invitó a participar a los bailarines de la escuela de samba de Mangueira. La escritora Anna Dezeuze anota que “La irrupción de los pobres en la atmósfera burguesa del museo causó tal escándalo que el director los desalojó. Cuando empeoró la censura en Brasil en la segunda mitad de los sesenta, la asociación de Oiticica con Mangueira lo conectaría más con la resistencia a la dictadura que había tomado el poder en 1964”.2 Lo que cuarenta y un años más tarde nos puede parecer meros ejercicios en las posibilidades formales y conceptuales del arte está enraizado no sólo en la cultura carioca sino también en una filosofía del arte como instrumento de revolución —si bien no política, por lo menos de conciencia cultural—. El gesto de Oiticica hacia sus amigos obreros de Mangueira, a sólo un año de la deposición del presidente izquierdista Joao Goulart por un golpe de estado derechista no sólo era una provocación sino también un acto de suma peligrosidad. Ese régimen militar estuvo caracterizado por la tortura, encarcelamiento, desaparición y asesinato de políticos, estudiantes, escritores y artistas.3

La obra de Oiticica tiene también un trasfondo artístico cultural. En 1950 el suizo Max Bill, apóstol confeso del arte concreto, tuvo una exposición en el recientemente inaugurado Museu de Arte de Sao Paulo y, al año siguiente, ganó un premio importante en la primera Bienal de Sao Paulo. De acuerdo con Edward J. Sullivan, Max Bill “inspiró a muchos jóvenes artistas en Brasil a trabajar en un estilo similar al suyo”.5 El término “arte concreto” proviene del Manifiesto del Arte Concreto (1930) de Theo van Doesburg. El axioma principal de esta práctica artística fue crear obras que fueran “objetivas” e independientes de todo simbolismo o realidad observada. En esencia, apuntaba a crear arte no figurativo que no denotara nada que no fuera él mismo. Estas ideas artísticas hallaron suelo fértil en Brasil en tanto coincidían con las ideas reinantes de industrialización y renovación arquitectónica. Como resultado aparecieron dos núcleos de arte concreto en Brasil. En Sao Paulo se formó el Grupo Ruptura en 1952. Entre otros, incluía a Waldemar Cordeiro, Luís Sacilotto, Geraldo de Barros y Anatol Wladislaw. El Grupo Frente se consolidó en Río de Janeiro en torno al artista abstracto Iván Serpa con una exposición en la galería del IBEU (1954). Al cabo de un par de años el grupo incluiría a Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape, Décio Vieira, los hermanos César y Hélio Oiticica, Franz Weissman, Abraham Palatnik y otros pintores y poetas.

Dadas las muy distintas culturas de Sao Paulo y Río de Janeiro, Ruptura y Frente estaban destinados a chocar. En ocasión de la 1ª Exposição Nacional de Arte Concreta que se inauguró en Sao Paulo en 1956, los miembros de Ruptura criticaron a los de Frente por su carencia de rigor estructural y por permitir que la expresión lírica contamine el arte concreto. El riguroso acatamiento del grupo Ruptura a los principios del arte

Dadas las muy distintas culturas de Sao Paulo y Río de Janeiro, Ruptura y Frente estaban destinados a chocar. En ocasión de la 1ª Exposição Nacional de Arte Concreta que se inauguró en Sao Paulo en 1956, los miembros de Ruptura criticaron a los de Frente por su carencia de rigor estructural y por permitir que la expresión lírica contamine el arte concreto. El riguroso acatamiento del grupo Ruptura a los principios del arte

concreto internacional era demasiado restrictivo para el más ecléctico grupo Frente. El cisma llevó a Ferreira Gullar a escribir el Manifiesto Neoconcreto (1959) para la 1ª Exposição de Arte Neoconcreta en el Museu de Arte Moderna en Río de Janeiro. Allí Gullar objetaba la “peligrosa exacerbación racionalista“ del arte concreto y proponía devolverle al arte su dimensión existencial, emotiva y afectiva. Más aún, acercándose a lo que Oiticica vislumbraría más tarde, Gullar articuló la idea de que “no concebimos la obra de arte como una `máquina´ ni un `objeto´ sino como un cuasi-cuerpo”. Para enfatizar la liberalidad neoconcreta, Gullar aclaró que los artistas neoconcretos no constituían un “grupo” regido por principios dogmáticos. A la larga los afiliados al neoconcretismo incluirían a Lygia Clark, LygiaPape, Amílcar de Castro, Franz Weissmann, Sergio Camargo, Ferreira Gullar, Aluísio Carvão, Décio Vieira, Hélio Oiticica, Hércules Barsotti, Willys de Castro, etc. Algunos, como Clark, Pape y Oiticica, resaltaban la importancia del dinamismo y la interacción física entre las obras de arte y su público.

El nombre de la actual exhibición de Hélio Oiticica, El cuerpo del color, viene de una de sus propias reflexiones. “El color, afirmó, `tiende a in-corporarse’ —se hace temporal, crea su propia estructura, por lo que la obra se convierte en ‘el cuerpo del color’—.” Esta exposición incluye la producción de Oiticica desde fines de los cincuenta hasta fines de los setenta. En sus obras de fines de los cincuenta, el espectador encara obras en las que el color, el movimiento y las formas siguen los lineamientos del arte concreto brasileño. Son obras no-figurativas, geométricas y destinadas a colgar de la pared. Es con sus Relevos que Oiticica comienza la liberación del color de su existencia rectangular y bidimensional. Los Relevos semejan coloridos origami flotando en el espacio: geométricos y mínimamente volumétricos —de allí el nombre “relieves”—.

En el inventario del opus de Oiticica hay tres tipos de objetos de particular importancia: bólides, penetráveis y parangolés. Para Oiticica, los bólides (en español, “bólidos”) reflejaban los colores y estructuras de las favelas. Los bólides caxias son curiosas cajas que se pliegan, tienen cajones, almacenan pigmentos, piedritas, conchas, espejos o fotografías. Con frecuencia están hechos de materiales recogidos de la calle y pintados de amarillo, anaranjado o rojo brillantes. Hay también bólides de vidrio, como aquél hecho de un cilindro de vidrio casi lleno de pigmento rosado y dentro del cual se inserta un cubo. En última instancia estos “bólidos” separaron la obra de Oiticica del principio del arte concreto que impedía la representación. Los bólides son objetos concretos que también representan, no por medio de la similitud, sino por ser muestras de las estructuras y despojos urbanos.

En noviembre de 1964, Oiticica escribió: “El descubrimiento de lo que llamo `parangolé´ (jerigonza que nombra una situación de súbita confusión o algarabía), marca un punto decisivo y define una posición específica en el desarrollo teórico de toda mi experiencia con la cuestión de la construcción tridimensional del color”. El parangolé es un tipo de capa, banderola o incluso carpa hecha de tela, papel, plástico, paja o soga cosidos, pintados o dibujados. Los parangolés fueron inspirados por las capas que visten los bailarines de la escuela de samba de Magueira, a la cual pertenecía Oiticica. El aspecto conceptual más importante de estas obras es que son arte para ser vestido. Es la participación del espectador quien les da a estas esculturas móviles sus formas cambiantes y, al ponérselas, aquél se convierte en parte activa de la obra.

La interactividad del arte es también un ingrediente central de los penetráveis de Oiticica. Estas son obras de arte para ser habitadas tanto como los parangolés son para ser vestidos. Cuando los participantes ingresan en el penetravel y se desplazan de un recinto al siguiente, experimentan diferentes sensaciones y sentimientos. Con frecuencia estas construcciones semejan las viviendas improvisadas de las favelas donde una cortina o una estera puede usarse en vez de una pared y los dormitorios son poco más que cajas. Oiticica invitaba a los participantes a entrar descalzos y habitar esos espacios con actividades de ocio tales como acostarse. La primera de estas obras ambientales fue “Tropicália”, la cual fue montada en el Museo de Arte Moderno de Río de Janeiro en 1967. Fue una obra crucial que propició en Brasil el movimiento Tropicalista en todas las artes: teatro, cine, poesía, artes visuales y música popular.

Aristóteles vislumbró que la filosofía comenzaba con el otium— palabra que en español viene a ser ocio— queriendo decir tiempo libre. En otras palabras, si no tienes ocio porque tienes que encargarte de tu neg-ocio (la negación del ocio), no puedes dedicarte a los asuntos de la filosofía. De manera similar, Oiticica inventó el neologismo “crelazer” que significa “creer en el ocio.” Para él crelazer se basaba en la alegría y el conocimiento fenomenológico y era un requisito para la creatividad. Asimismo —de una manera no muy distinta a Aldous Huxley y Timothy Leary— Oiticica creía también en la expansión de la percepción para potenciar el ser creativo: lo llamaba lo “supra-sensorial”. Lo supra-sensorial podía alcanzarse mediante estados alucinógenos, trances religiosos y el tipo de delirio al que se llega cuando se baila samba. En sus propias palabras, “Toda la experiencia dentro de la cual fluye el arte, la libertad misma, la expansión de la conciencia del individuo, el retorno al mito, el redescubrimiento del ritmo, la danza, el cuerpo, los sentidos, son finalmente lo que tenemos como armas de conocimiento directo, perceptivo y participativo… esto es revolucionario en el sentido total del comportamiento”.

NOTAS

1. La curadora de arte latinoamericano de MFAH, Mari Carmen Ramírez, es coautora del libro de próxima publicación The Body of Color.

Es por eso que —aunque no hay créditos curatoriales en la exhibición ni en el website del MFAH—, suponemos que es ella la curadora de The

Body of Color.

2. El abuelo de Hélio Oiticica fue anarquista; el padre, José Oiticica, escribió el libro El anarquismo al alcance de todos (1945).

3. Anna Dezeuze, “Tactile dematerialization, sensory politics: Helio Oiticica’s Parangoles”, Art Journal, verano, 2004.

4. Encyclopedia of Latin American. Editado por Barbara Tenenbaum, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1996.

5. Brazil: Body and Soul, editado por Edward J. Sullivan,Guggenheim Museum, 2002.

whoah this magazine is excellent i like reading your articles.

Keep up the good work! You recognize, many people are searching round for this information, you could help them

greatly.