A DEAD ELEPHANT

UN ELEFANTE MUERTO

Javier Zamudio

English translation by Tanya Huntington

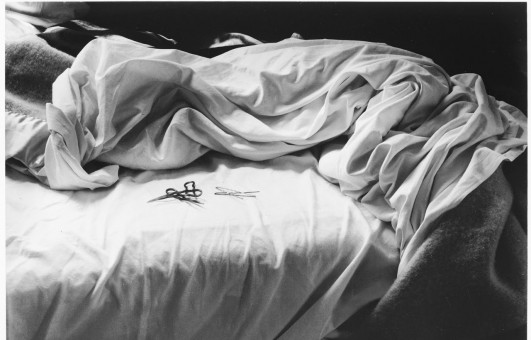

Manuel encountered a dead elephant lying on top of his bed. He held his nose to shield himself from the rotten stench that swamped the room. Flies buzzed over the trunk that flopped to one side, issuing a thread of dry blood that stained the sheets and some of the floor tiles. He had spent the night on the sofa after correcting his students’ exams for several hours. It occurred to him that if he had fallen asleep in bed, he would no doubt be in the same state as the elephant, asphyxiated beneath its enormous belly or choked between its legs. He contemplated the window, then the door. A quick calculation confirmed there was no way the elephant could have passed through either opening. He walked around the bed to the window. His apartment was located on the fourth floor of a building in the San Fernando district. He could see Quinta Street in the distance, the Pascual Guerrero stadium, and the weather-beaten walls of the Departmental Hospital. He abandoned the bedroom for the bathroom, where he splashed water on his face, then checked himself in the mirror. He rubbed his beard, stuck out his tongue, wet his lips. He combed his hair. He could find nothing odd about his appearance.

He headed back into the living room and over to the coffee table, where the exams were stacked. He inspected them and confirmed everything was just as he had left it the night before. There was nothing out of place, except for the dead elephant on top of his bed. As he returned to the bedroom, his stomach cramped. He approached the elephant, held one of its legs and felt the wrinkled skin beneath his fingertips. He caressed its back, which had taken on the rigidity of rigor mortis, then continued to run his open hand over its head, which resembled two small hillocks. He was reminded of Ernest Hemingway’s “Hills like White Elephants,” then saw the book of short stories sitting there on the nighttable, next to his bed.

This was no white elephant. It was blue, like a cloudless sky tinged with melancholy nightfall. Manuel managed to find the telephone. He called his father.

As the number started ringing, he became even more nervous. He imagined his father’s expression: raised eyebrows, lips curved downward, cheekbones reddened with anger. He was certain that he would not believe him, that he would start railing against his lifestyle.

“There’s a dead elephant on top of my bed,” he said as soon as he heard a voice answer, cutting off the question he heard every single time he called or visited his parents: “How are things going?”

“What?” His mother asked.

She was far more insistent than his father. When Camila, his wife, had left him, taking her granddaughters off to Bogotá, she had experienced a kind of aversion toward her son. Two months had gone by since the day when Manuel, his wife at work and his daughters at school, had made love to one of his colleagues on the bed where the dead elephant now lay.

“It’s me, Mom. Is Dad home?”

The voice disappeared. Then he heard his father’s.

“How are things going?”

The question annoyed him. He felt the urge to hang up, but managed to contain himself.

“There’s a dead elephant on my bed,” he said.

“Are you drunk? Are you on drugs?”

“I am not drunk, and I am not on drugs, Dad. I am telling you the truth. There is a dead elephant on top of my bed.”

His father cursed under his breath and fell silent for a few moments. Then he said:

“If there really is an elephant in your apartment, tell me how it managed to climb up four flights of steps. What you are saying makes no sense. Either you are drunk, or you’ve finally gone insane. That is what happens when you let your life fall apart.”

Manuel hung up the phone, certain now that talking to his father would only make things worse. Then he dialed the police and explained the situation to an officer.

“Are you saying you killed an elephant on the premises?”

“No. I did not kill it. I found it lying dead on top of my bed.”

“If you didn’t kill it, then who did?”

“I don’t know. When I woke up, there it was. I fell asleep on the sofa,” he explained.

“Are you telling me that a dead elephant appeared in your room, and you have no idea how it got there?”

Manuel hung up, startled. He brought a chair in from the dining room and sat down near the bed to examine the elephant more closely. He knew that his father and the police officer were right: how could there possibly be a dead elephant in his room? How did it get there? Why hadn’t he heard it? How had it managed to get across the threshold without him noticing? “I have gone crazy,” he said to himself, rubbing his face, slapping his cheeks. “I’ve got to call someone to come over and tell me I’m not insane.”

An hour later Alejandra, his lover, knocked hesitantly on the door. She could not help thinking about what had happened the last time she was there, in that apartment: Manuel had started to cry after making love to her. He’d rolled over like a little boy to one side of the bed and sat there, head buried between his hands, sobbing so hard you could hear him a block away.

Manuel opened the door and felt his stomach cramp up again, as if his wife were watching, or his children. Alejandra came closer and gave him a kiss. She wasn’t sure why he had called, but she figured the invitation heralded the beginning of a more serious relationship. The day before, someone had told her Camila had left Manuel and she had felt a wild joy. Happiness over someone else’s misfortune. He barely returned the kiss. She felt his cold lips and her heart raced. She threw her arms around him and started to unbutton his shirt.

“Wait! That’s not why I called you.”

Alejandra stopped, hands in mid-air, inhaling his turgid breath and regarded him for a moment, awaiting an explanation that failed to appear. Then she started in again. She pulled off his shirt while carefully propelling him into the bedroom. Manuel dared not say anything out of fear she would think he was insane. He turned the words over, searching for the right ones to explain that there was a dead elephant on top of his bed. Alejandra did not ask him why he hadn’t shown up for work. She didn’t tell him what the principal had told her when seven in the morning rolled around, that he was sorry she had fallen for a man like him: a puppet, a Nobody, a failure, a two-bit jerk who didn’t even bother to prepare his lessons. Nor did she tell him what a big mess it was when they had Ricardo, the Phys Ed teacher, take over his classes. She continued to guide him, pulling his pants down while removing her own clothes at short intervals. As they went through the doorway into the bedroom, Manuel cried out:

“There’s a dead elephant on my bed!”

Alejandra stopped short, raising her head to see tangled sheets and the pillow on the floor. She did not see any elephants.

“Is this some kind of joke?” She asked, pulling away from her lover.

Manuel turned away and there it was, the carcass of the elephant surrounded by a swarm of flies. Alejandra embraced him again and he let himself be carried away, convinced that no matter what he said, it would make no sense to anyone but him. They lay down on the bed next to the elephant’s legs and made love. Manuel could feel the stench of decomposition running down the back of his throat and saw the crystalline, transparent eyes of the elephant reflecting his own, blurred image, deformed since his wife left him. He felt like crying, but managed to contain himself. He closed his eyes and imagined Alejandra was Camila, and that it was just the two of them sprawled across the bed.

Manuel encontró un elefante muerto sobre su cama. Se tapó la nariz, protegiéndose del hedor a descomposición que se había apoderado de su habitación, mientras observaba las moscas sobre la trompa que caía a un costado dejando escapar un hilo de sangre seca que manchaba la sábana y parte de las baldosas. Había pasado la noche en el sofá, luego de leer durante varias horas los exámenes de sus estudiantes. Pensó que si por error hubiese dormido en su cama, con seguridad acompañaría al elefante, asfixiado debajo de su enorme panza o estrangulado entre sus patas. Miró la ventana y después la puerta. Haciendo un cálculo ligero, concluyó que era imposible que el elefante hubiese entrado por ambas aberturas. Rodeó la cama y se aproximó a la ventana. Su apartamento estaba ubicado en el cuarto piso de un edificio del barrio San Fernando. Vio en la distancia la calle Quinta, el estadio Pascual Guerrero y las paredes curtidas del Hospital Departamental. Salió del cuarto en dirección al baño, se lavó la cara y se miró en el espejo. Palpó su barba, sacó su lengua y mojó sus labios, peinó su cabello. No notó nada raro en su apariencia.

Se dirigió a la sala, se acercó a la mesa de café donde estaban los exámenes e inspeccionó el paquete comprobando que estaba como lo había dejado la noche anterior. Todo lucía de la manera acostumbrada, excepto por el elefante muerto sobre su cama. Regresó a la habitación sintiendo un retorcijón en el estómago. Se acercó al elefante, tocó una de sus patas y sintió la piel rugosa en la yema de sus dedos. Acarició su lomo, que había adquirido la rigidez del rigor mortis, y continuó con su mano abierta sobre la cabeza que parecía formada por dos pequeñas colinas. Recordó el relato de Ernest Hemingway Colinas como elefantes blancos y vio el libro de cuentos puesto al lado de la cama, sobre el nochero.

No era un elefante blanco. Era azul como un cielo sin nubes teñido por un ocaso triste. Manuel buscó el teléfono y llamó a su padre.

Escuchó el pito del teléfono y se puso todavía más nervioso. Imaginaba el gesto de su papá: las cejas levantadas, los labios curvados hacia abajo y los pómulos ligeramente sonrosados de rabia. Estaba seguro que no le creería y empezaría a despotricar sobre su vida.

«Hay un elefante muerto en mi cama», dijo al oír una voz, sin dar tiempo a la pregunta que escuchaba cada vez que llamaba o visitaba a sus padres: «¿Cómo va tu vida?»

«¿Qué?», preguntó su madre.

Ésta era más insistente que su padre. Desde que Camila, su mujer, lo abandonó llevándose a sus hijas a Bogotá, ella sentía cierta aversión por su hijo. Dos meses antes, mientras su mujer trabajaba y sus hijas estudiaban, Manuel había hecho el amor con una de sus colegas sobre la cama donde yacía el elefante muerto.

«Soy yo, mamá. ¿Papá está?»

La voz desapareció y luego oyó la voz de su padre.

«¿Cómo va tu vida?»

La pregunta lo irritó. Quiso colgar pero se contuvo.

«Hay un elefante muerto en mi cama», dijo.

«¿Estás borracho o consumes drogas?»

«¿Qué? No estoy borracho y no consumo drogas, papá. Te estoy diciendo la verdad. Hay un elefante muerto en mi cama»

Su padre susurró una maldición y guardó silencio un instante. Luego dijo:

«Si hay un elefante en tu apartamento explícame cómo subió los cuatro pisos. Lo que dices no tiene ningún sentido. Si no estás borracho entonces finalmente te enloqueciste. Eso te pasa por no ponerle orden a tu vida»

Manuel colgó convencido de que hablar con su padre empeoraría las cosas. Marcó el número de la policía y le explicó a un oficial lo que pasaba.

«¿Me está diciendo que mató un elefante en su residencia?»

«No. No lo maté. Lo encontré muerto sobre mi cama»

«Si no lo mató, ¿quién lo hizo?»

«No lo sé, cuando desperté estaba allí. Dormía en el sofá», explicó.

«¿Me quiere decir que apareció un elefante muerto en su habitación y no sabe por qué?

Manuel colgó asustado. Trajo una silla del comedor y se sentó cerca de la cama a mirar el elefante. Sabía que su padre y el policía tenían razón: ¿cómo era posible que hubiese un elefante muerto en su cuarto? ¿Cómo había entrado? ¿Por qué no lo había escuchado? ¿De qué manera había franqueado la entrada sin llamar su atención? «Enloquecí», se dijo palpándose la cara, dándose golpecitos en los cachetes, «tengo que llamar a alguien para que venga, para que me diga que no estoy loco».

Una hora más tarde, Alejandra, su amante, golpeaba la puerta con timidez. No podía olvidar lo ocurrido cuando estuvo en aquel apartamento: Manuel se puso a llorar después de hacer el amor con ella. Rodó como un niño hacia un costado de la cama y se sentó con la cabeza escondida entre las manos, dejando escapar un llanto que podía oírse desde el primer piso.

Manuel abrió la puerta y sintió otro retorcijón en el estómago, como si su mujer o sus hijos estuviesen viéndolo. Alejandra se acercó y lo besó. No estaba segura por qué la había llamado pero supuso que aquella invitación era el comienzo de una relación en serio. Un día antes se había enterado de que Camila había abandonado a Manuel y había sentido una alegría extraña. Felicidad por el mal ajeno. Él apenas le devolvió el beso. Ella sintió sus labios fríos y su corazón se aceleró. Lo abrazó y empezó a quitarle la camisa.

«¡Espera! No te he llamado para eso».

Alejandra se detuvo, con las manos en el aire y respirando su aliento turbio; lo miró un momento aguardando una explicación que no llegó. Entonces reanudó su tarea. Lo despojó de la camisa mientras iba empujándolo hacia el cuarto. Manuel no se atrevía a decir nada por temor a parecer un loco. Daba vueltas a las palabras buscando las adecuadas para explicar que había un elefante muerto sobre su cama. Alejandra no le preguntó por qué no había ido a trabajar. No le contó lo que había dicho el rector cuando se acercó a las siete de la mañana para decirle que lamentaba que ella hubiese terminado enamorada de un hombre como él: un pelele, un don nadie, un fracasado, un tipejo de poca monta que ni siquiera preparaba sus clases. Tampoco le dijo del lío que se armó porque tuvieron que hacer que Ricardo, el profesor de Educación Física, se ocupara de sus cursos. Continuó empujándolo, quitándole los pantalones mientras, en intervalos cortos, ella se despojaba también de su ropa. Cuando cruzaron el umbral del cuarto Manuel gritó:

«Hay un elefante muerto en la cama»

Alejandra se detuvo, alzó la cabeza para ver la sábana revuelta y la almohada en el piso. No vio ningún elefante.

«¿Es un tipo de chiste?», preguntó alejándose de su amante.

Manuel volteó y ahí estaban los restos del elefante, rodeados por un pelotón de moscas. Alejandra lo abrazó de nuevo y él se dejó llevar convencido de que cualquier cosa que dijese no tendría sentido para nadie, excepto para él. Se acostaron en la cama, junto a las patas del elefante e hicieron el amor. Manuel podía sentir el hedor a descomposición recorriendo su garganta y veía los ojos cristalinos, transparentes del elefante, que lo reflejaban de manera imprecisa, como si se hubiese deformado tras la partida de su mujer. Sintió deseos de llorar, pero se contuvo. Cerró los ojos e imaginó que Alejandra era Camila y que sólo estaban ellos dos derramándose sobre la cama.

Javier Zamudio (Cali, Colombia, 1983). Sus cuentos aparecen en revistas como El Malpensante, Hermano Cerdo, Luvina, Número y Odradek. Es autor de El infierno de los otros (Universidad del Valle, Cali, 2009), Soñábamos con el amor (Caza de Libros Editores, Tolima, 2015) y Hemingway en Santa Martha (Lugar Común Editorial, Ottawa, 2015). Twitter: @JavierZamudioE

Javier Zamudio (Cali, Colombia, 1983). Sus cuentos aparecen en revistas como El Malpensante, Hermano Cerdo, Luvina, Número y Odradek. Es autor de El infierno de los otros (Universidad del Valle, Cali, 2009), Soñábamos con el amor (Caza de Libros Editores, Tolima, 2015) y Hemingway en Santa Martha (Lugar Común Editorial, Ottawa, 2015). Twitter: @JavierZamudioE

Qué buena forma de contar una historia en unos cuantos párrafos.

Precisa, interesante y muy bien lograda.

Me gusto.