Gustavo Díaz: the fuzzy garden

Fernando Castro R.

Confronting silence by uttering a sound is nothing

but verifying one’s own existence.

Toru Takemitsu

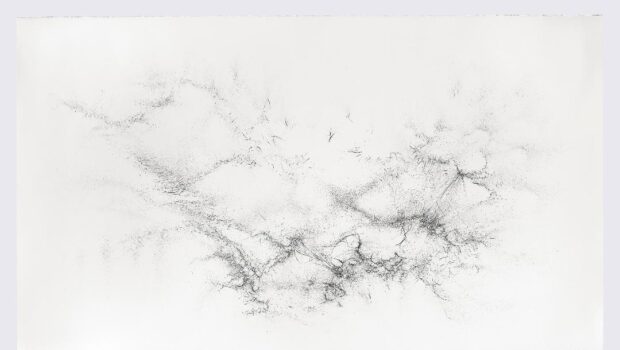

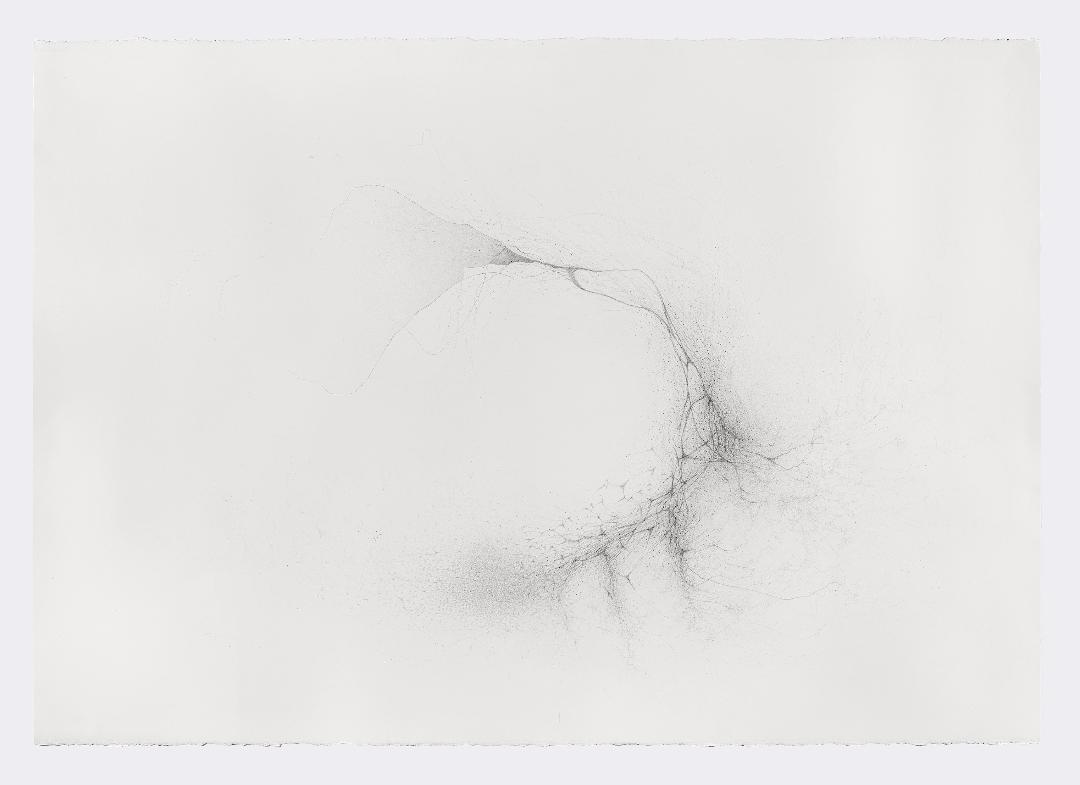

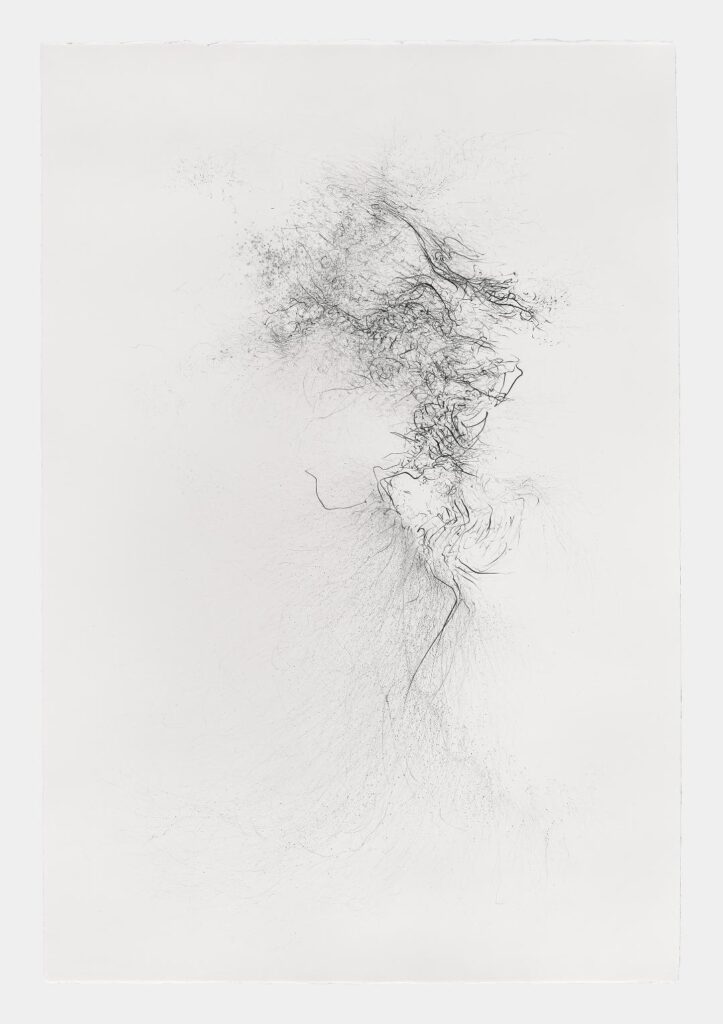

Gustavo Díaz’s exhibit Confronting Silence at Sicardi Ayers Bacino Gallery featured a dozen large graphite drawings on paper. The title of the exhibit comes from a book of essays by Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu (1930-1996). At first sight, some of Díaz’s drawings look like neural networks, aerial views of urban centers, or the ever-evolving wondrous patterns made by certain species of birds when they fly synchronously. The viewer of Confronting Silence is lured into seeking a likeness where there may or may not be any, as is the case of the face on Imaginary Flight Patterns I. However, it is not the game of mimicry but perhaps of modelling in the mathematical sense that is at stake; one in which many, albeit not all, interpretations are supported and encouraged by the works. Thus, while one drawing may suggest subtle sumi-e landscapes, other drawings are like things one would never see because they are nowhere to be seen by the naked eye, except in the drawing itself, or because the referents are observed only by scientists with sophisticated observation tools or via mathematical constructs. Yet, the most astounding visual attributes of this particular group of drawings —even if one were to deny that they mimic anything at all— are the very implausible yet actual hand-drawn lines that define them. Confronting Silence is a very cerebral exhibit, while at the same time it is a tour-de-force of the very physical act of drawing.[i]

It is no wonder then that one of the few emotions induced by viewing Díaz’s drawings happens when the viewer gets close enough to discern their intricate minutiae. Then the viewer may ask herself or himself about the prowess and precision skills required to draw those lines so incredibly and impeccably close to one another. Where does the artist place his body in order to render lines with that exactitude in such large surfaces? If artistic technique is at times missing from conceptual artworks, Díaz’s drawings are a clear counterexample. In fact, he readily admits that he had to retrain his hand and arm in order to undertake this series of drawings. In a 2012 interview he stated “In the Bauhaus tradition it was said that there is a knowledge that travels from the head to the hand and another from the hand to the head.”[ii] Previous works (equally astounding by their own merits) started as drawings made manually but on an electronic device that mediated between his physical marks and the final products. The technique in both cases is vastly different although the resulting products are equally mind-boggling. By design, Díaz’s drawings are not randomly gestural as may be a Paul Jenkins, nor are they algorithmic, as may arguably be a Mondrian or a Vasarely drawing. These drawings that at a distance of three meters may appear as products of spontaneous doodles are at thirty centimeters the polar opposite of gesturing. The artist draws with such precise intentionality that any gesture would result in a blunder.

If not spontaneous, what rules or patterns does Díaz follow? In these days when expressing the artists’ identities and communities in their works is of paramount concern, Díaz is one of those artists who takes his intellectual community and rules to be the ones suggested in the “constellation.”[iii] That long print-out of the “constellation” displayed as part of the exhibit is a kind of Rosetta stone from which to think about the multivalency of Díaz’s works, whether a single work may simultaneously denote the trajectories of gas molecules in Brownian motion, the spatial form of an avant-garde composition by Iannis Xenakis Pithoprakta, or any other whimsical interruption of silence.[iv]

Gustavo Díaz, From the series: Imaginary Flight Patterns V, 2021. Graphite on paper, 46 x 63 7/16 x 2 1/4 in. (116.8 x 161.1 x 5.7 cm.) Courtesy of Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino. Houston, TX

Back to the title of the exhibit: how do these drawings confront silence? Excluding musical notation, can the connection between physical marks on a paper and musical sounds be more than metaphorical? Is the depiction of noise, and noise equivalent? When does noise become music, and vice versa? Díaz’s constellation shows his musical penchant for 20th century avant-garde composers (Messiaen, Stockhausen, Cage, et al.) who have explored the latter question. Indeed, Confronting Silence includes sound compositions by Díaz which may be better judged by a music critic rather than the undersigned. Moreover, some of Díaz’s titles are a variation of Takemitsu’s composition “A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden” (1977), which becomes “Flock ascending to the quantum garden” (2021). Díaz himself has described it as “an attempt to switch to a non-Euclidian way of thinking.” The variation ushers in the topics of probability and uncertainty. One of the main touchstones in Díaz’s constellation is fuzzy logic, a type of multivalent logic that admits intermediate values between the truth and falsity (one and zero in our friendly computers) of bivalent traditional logic. In fact, one of the books in Díaz’s constellation is Fuzzy Sets, Fuzzy Logic, and Their Applications, inspired by Lotfi Zadeh’s seminal book Fuzzy Sets, Fuzzy Logic, and Fuzzy System). At the core of Díaz’s artistic oeuvre and aesthetics is this idea of a continuum between noise and music, stochastic and stubbornly random processes, mimicry and abstraction, corporeality, and virtuality.[v]

Two other loci in Díaz’s constellation are worth exploring in the process of understanding the ideological horizon of his drawings. The first is the visual atlas (Bilderatlas) of art historian Aby Warburg (1866-1929) and the second one is the writings of Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986). Indeed, Díaz’s constellation is a model of Warburg’s atlas. The idea behind both is to find interesting similarities or connections in a set of seemingly disparate objects, and important differences in a set of like objects. Warburg executed this idea in a way that upset art historical orthodoxy because it transgressed space and time, geography and culture, art, and the media. In addition to amassing an important art historical bibliography, Warburg assembled the Bilderatlas Mnemosyne (1927-29): sixty-three panels with 971 photographic reproductions of artworks from antiquity to his day, mixed-in with newspaper clippings, stamps, coins, ads, and the like. The proximity of the objects in each panel suggested connections that went beyond similarity, and into psychological, sociological, and cultural connections.

What about Borges’ literary oeuvre in Díaz’s works and constellation? A couple of Borges narratives are alluded to in these works. The first, On the rigor of science, is about the absurdity of an enormous comprehensive map that, in order to leave nothing out, becomes the size of the mapped empire. Are Díaz’s drawings a kind of cartography? At least one of the drawings, Imaginary Flight Patterns IV, bears a resemblance to an aerial view of an urbanized area. In some of Díaz’s drawings what is represented may be something you will not see in our dear visual world, like probability density clouds or the record of the most stepped-on areas of a soccer pitch during the course of one or many games.

The second Borges story, De la salvación por las obras, is about eight Shinto deities who are considering the elimination of the human species in order to save the world.[vi] Only one of the deities argues against that terminal idea, submitting that in spite of the fact humans have done terrible things, they have also created haikus, or (here Borges’ language is ambiguous) one specific imperfect haiku; perchance, “por obra de un haikú, la especie humana se salvó” (thanks to a haiku, the human species was saved). The entire weight of human existence bearing down on seventeen syllables? Although we tend to be less optimistic about the power of a haiku to save the world and reluctantly agree with the other seven Shinto deities, we hasten to ask whether there is something as apocalyptic in the drawings of Confronting Silence.

Gustavo Díaz, Flock ascending to the quantum garden, 2021. Graphite on paper, 48 5/16 x 33 11/16 x 2 1/8 in. (122.7 x 85.6 x 5.4 cm.) Courtesy of Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino. Houston, TX

Diaz’s drawings leave us with unanswered questions. Does the vast white empty space in Díaz’s drawings stand for silence and the drawn lines the music? Or conversely, if the white spaces are the noise, are the graphite marks the structure of silence? Díaz once stated, “I declare myself a fervent defender of the world of questions, not so much of that of answers. I am fascinated by the realm in which we question, where there is room for doubt; given that we open pathways toward reflection.”

ENDNOTES

[i] Seventeen years ago, the book Vitamin D: New Perspectives in Drawing (Phaidon: London, 2005) attempted to give a glimpse of the state-of-the-art of drawing. As with any curatorial endeavor, it is a moot question whether all the artists included ought to have been, and which excluded ones should have been included. However, the book is worth perusing to compare and contrast Gustavo Díaz’s current work with that of artists such as Daniel Zeller and Julie Mehretu, whose work is featured.

[ii] Salum, Rose Mary. Interview: “Gustavo Díaz: the Art of Questioning,” Literal 28, Spring 2012.

[iii] In 1997, MFAH curator Mari Carmen Ramírez also used the metaphor of “constellation,” although not as a compass for a hermeneutic of artworks as Díaz does but rather as a structural guide for her curatorial endeavor. She wrote, “Instead, both the exhibit and the accompanying catalogue have been conceived as a constellation. That is, an arbitrary configuration of seemingly ecclectic [sic], often competing, visions and attitudes toward drawing which came into being during the 1960s and 1970s in the Southern Cone and have continued to unfold into the present.” [Re-Aligning Vision: Alternative Currents in South American Drawing. Ed. Mari Carmen Ramírez. The University of Texas: Austin, 1997]

[iv] The intentional fallacy is a phrase coined by the American New Critics W.K. Wimsatt Jr. and Monroe C. Beardsley in a 1946 essay that challenges the common assumption that an author’s declared or assumed intention in writing a work is a proper basis for deciding the work’s meaning. First, I do not believe that Díaz’s constellation is relevant to the fallacy. Secondly, said fallacy is not always a fallacy. For example, when Immanuel Kant made some changes in the 2nd edition of the Critique of Pure Reason because he was dissatisfied with the words that did not convey exactly what he meant, he was the main authority on what the work meant. Third, the fallacy was coined for written works, not for works of visual art, and it is my contention that the difference is crucial.

[v] Fuzzy logic is a form of multi-valued logic in which the true value of variables may be any real number between 0 and 1. According to Aristotelian logic, there are only two logical values: true or false, black or white. Although in real life some things are black or white, in many other things there are many shades of grey. For example, although being pregnant is either true or false, being “fit” may not be as clear-cut because fitness depends on many variables, including the individual herself. Fuzzy logic has been used in numerous applications such as facial pattern recognition, healthcare (radiographic image classification, image segmentation for tumors, etc.), control of subway systems and unmanned helicopters, et al.

[vi] “De la salvación por las obras,” Atlas. Jorge Luis Borges. Sudamericana, Buenos Aires, 1984.

*Cover image: Gustavo Díaz, From the series: Imaginary Flight Patterns II, 2021. Graphite on paper, 56 3/16 x 95 x 2 1/4 in. (142.7 x 241.3 x 5.7 cm.)

Fernando Castro is an art critic, essayist and curator. He studied philosophy at Rice University thanks to a Fulbright grant. He is a Board Member of FotoFest and the Center for Photography in Houston. His articles have been published by Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal Magazine & Spot among others.

Fernando Castro is an art critic, essayist and curator. He studied philosophy at Rice University thanks to a Fulbright grant. He is a Board Member of FotoFest and the Center for Photography in Houston. His articles have been published by Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal Magazine & Spot among others.

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

Posted: August 25, 2022 at 10:37 pm